Honoring the life and legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. | Race and Culture

It took 15 years for the federal government to approve the MLK holiday and an additional 17 years for it to be recognized in all 50 states.

15 year battle The Fight for MLK Day

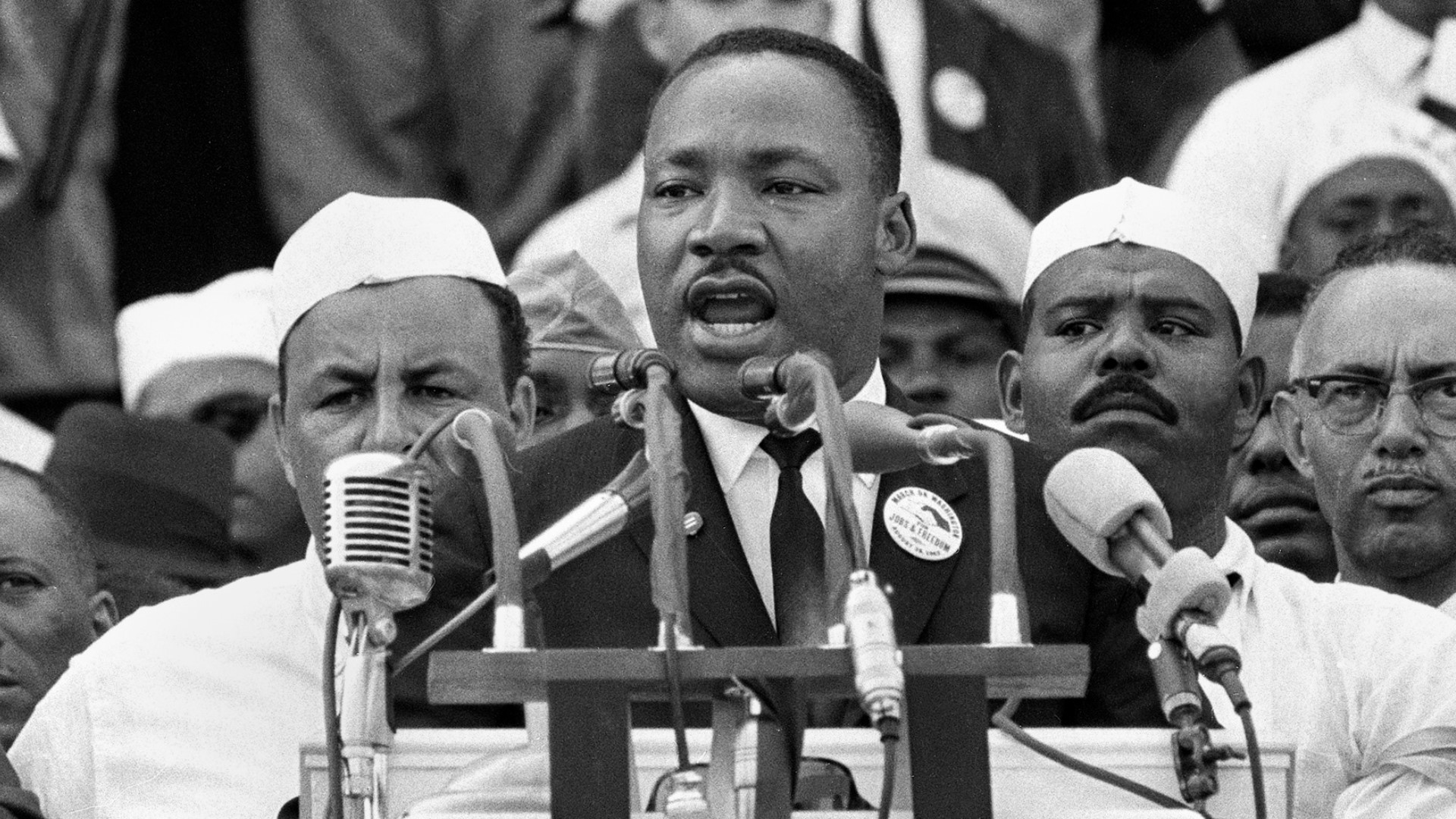

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, also known as MLK Day, is celebrated every year in the United States on the third Monday in January to honor the achievements of the civil rights leader who advocated for nonviolent resistance against racial segregation.

It's also the only federal holiday designated by Congress as a National Day of Service. Americans are encouraged to follow in Dr. King's footsteps by participating in public service activities.

“It's a day on, not a day off,” said Dr. Martin L. Boston, Assistant Professor in Pan African Studies and Ethnic Studies at California State University, Sacramento. “There is no better term to say who Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was than a servant. So, MLK Day is a time to think about the most marginalized, most under-resourced, most undervalued people, and think of ways that you can service those people.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day is, usually, celebrated nationwide with marches, parades, special ceremonies, and community service events. But it was a long battle to get MLK Day recognized as a national federal holiday.

Even though MLK Day represents an American hero, service, and unity among all, it took 15 years for the federal government to approve the holiday and an additional 17 years for it to be recognized in all 50 states.

“Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day took so long to become a holiday due to do the idea of racism and politics,” Boston said. “Both are hand in hand in a lot of ways, in creating the environment for why it took so long for King Day to be recognized and why it is still being contested to this very day.”

Democratic Michigan Congressman John Conyers first introduced the bill to make King's birthday a federal holiday on April 8, 1968, just four days after King's assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn.

Despite the nation mourning, the bill had limited congressional support. But, according to the National Museum of African American History, Representative Conyers continued to reintroduce the legislation every year with the support of the Congressional Black Caucus, which he helped found.

In 1979, on the 50th anniversary of King's birth, the bill finally came to a vote in the House. However, even with a petition of 300,000 signatures in support, the backing of President Jimmy Carter, and testimonials from King's widow, Coretta Scott King, the bill still was rejected by five votes in the House.

Republican Missouri Congressman Gene Taylor led the opposition, which cited the costs of an additional federal holiday and traditions which exclude private citizens from receiving recognition with public holidays named in their honor.

“It was a really close vote,” Boston explained. “But, it actually made some people even more enthusiastic about the idea of MLK Day, people, like Stevie Wonder.”

Motown singer and songwriter Stevie Wonder released the album "Hotter Than July" in 1980. It featured the song "Happy Birthday," which served as a tribute to Dr. King. Wonder also made regular appearances, alongside Coretta Scott King, at rallies in support of making Dr. King's birthday a federal holiday.

Additionally, Wonder ended a four-month tour with a benefit concert on the National Mall, where Dr. King delivered his famous “I have a Dream” speech 18 years earlier.

"The Happy Birthday song was a call for making King's birthday a holiday," Boston said. "Stevie Wonder used the song to galvanize a movement. In November 1980, Stevie Wonder went on tour. But, originally, Stevie Wonder asked Bob Marley to be part of the tour, too. And, Bob Marley agreed. But, soon after, Bob Marley went into the hospital for cancer. Six months later, Marley died in May 1981. So, originally, Bob Marley was going to be part of the tour, too. Instead, the poet and artist Gil Scott-Heron joined the tour [and] Coretta Scott-King and the King of Pop, Michael Jackson, also showed up during the tour."

In 1983, the King holiday bill, again, made it to the house floor. That's 15 years after King's murder. But, this time, support for the bill was overwhelming. Coretta Scott King, the Congressional Black Caucus, and Stevie Wonder worked together to get a six million signature petition in favor of the holiday.

The bill easily passed in the House with a vote of 338 to 90. After two days of debate, the bill passed in the Senate. President Ronald Reagan, reluctantly, agreed to sign it into law on Nov. 2, 1983.

“People should care about MLK Day,” Boston said. “You have, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, the ability to be a servant and there's nothing more human than to be a servant of mankind.”

Despite officially earning federal recognition, MLK Day still faces resistance in the form of other competing holidays.

Some states, like Alabama and Mississippi, continue to combine the MLK Day with "Robert E. Lee Day," to honor the birthday of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who led the South's attempt at secession during the American Civil War. However, Martin Luther King Day has been recognized in all 50 states since early 2000.

Remembering MLK In Dr. King's Presence

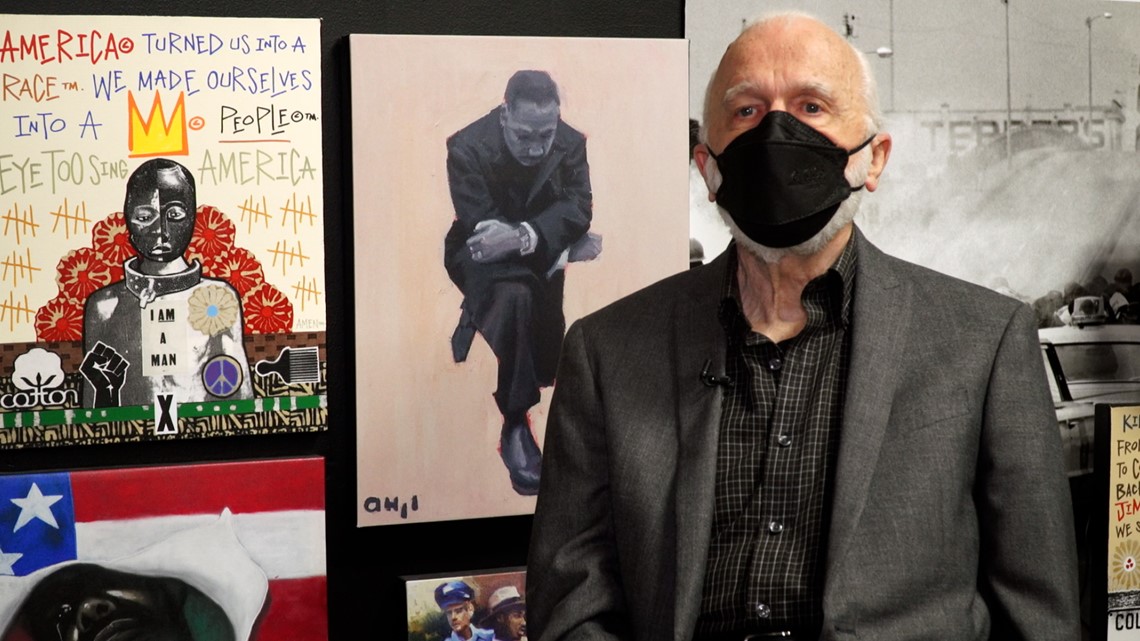

As the country honors the life and legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin L. King, Jr., Warren Bonta is remembering the life-changing moment he saw the civil rights icon.

Bonta is a community activist from Ventura County and now lives in Sacramento. He's also the father of Rob Bonta, the 34th Attorney General of the state of California and the first of Filipino descent and second Asian-American to occupy the position.

Warren Bonta says he first experienced the uplifting presence of Dr. King at the national Methodist Student Leadership Conference in Lincoln, Neb. in December 1964.

“It was unplanned,” Bonta said. “I went to a conference, and there he was. I just went with it. I was so thrilled by that. He just blew me away.”

More than 6,000 college students attended the event at the Pershing Memorial Auditorium. The Methodist Student Movement invited Dr. King to the conference.

“Dr. King had not been made known to the attendees, like myself, that he was going to be there,” Bonta explained. “That’s because half the kids there, like myself, their parents wouldn't let them come because Dr. King was trying to change our country. He was trying to rewrite history in terms of the Civil War and post-war.”

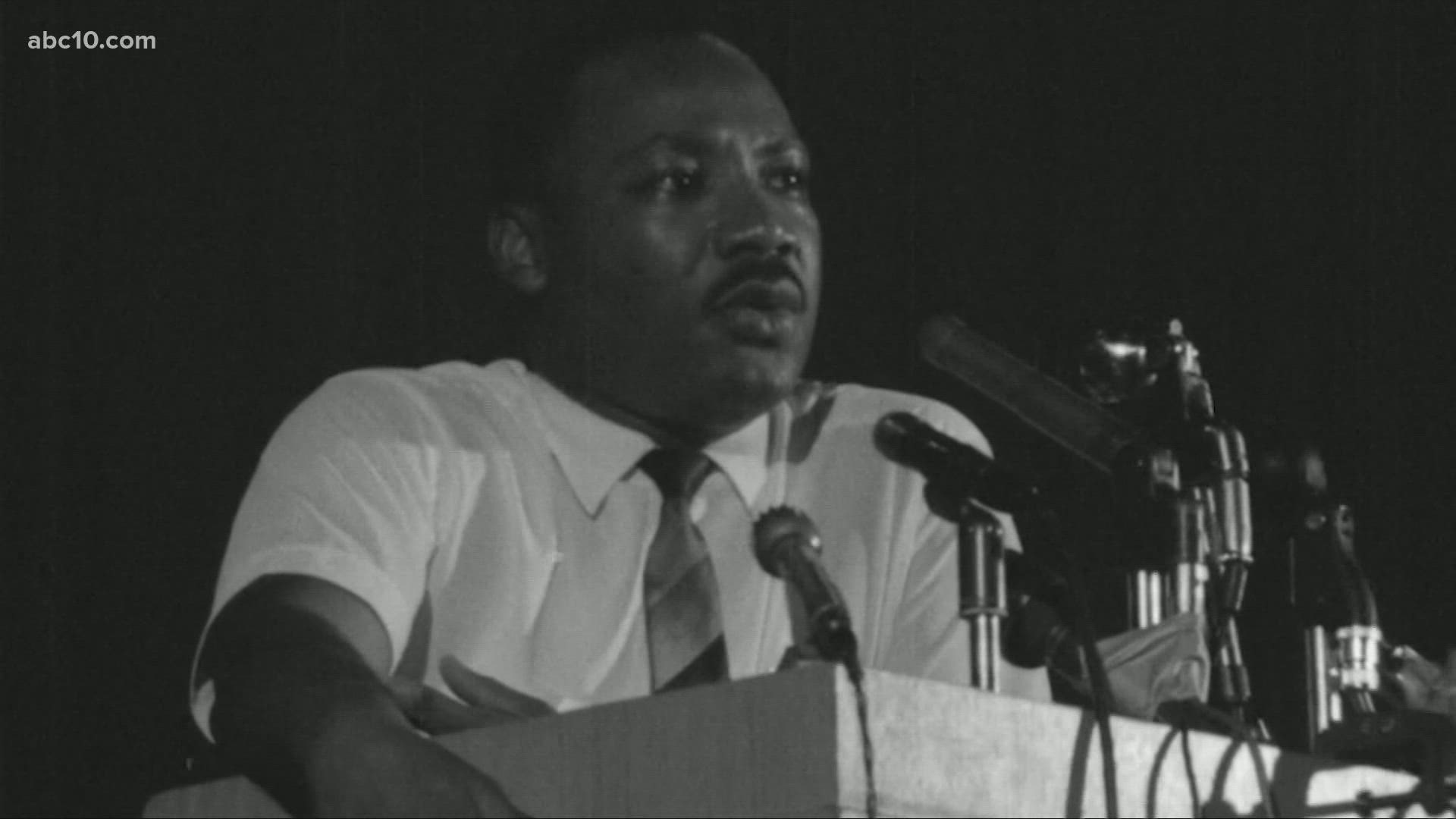

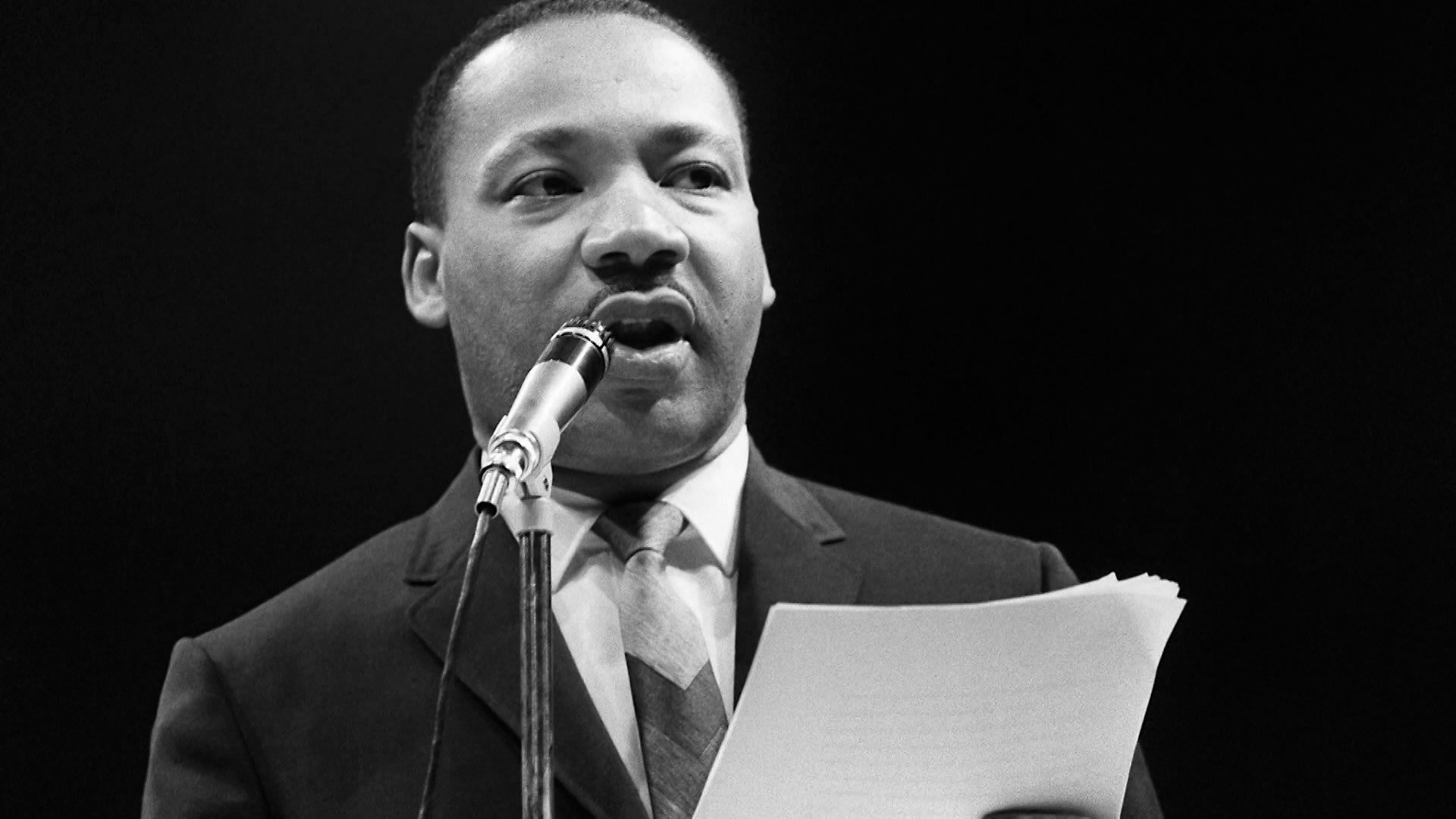

During the conference, Dr. King gave a speech on the civil rights struggle. Bonta says he still remembers how Dr. King’s voice filled the auditorium.

“He was amazing, such a great speaker,” Bonta said. “It’s a reassuring voice. It's powerful, but it's gentle and reassuring. So, that was the first time I had been in his presence.”

Bonta found himself in Dr. King's presence for the second time at the historic Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma, Alabama in April 1965. Dr. King put out a nationwide call for more support following the big march from Selma to Montgomery.

“He was compassionate, and I think he was a little bit of self-effacing,” Bonta said. “He was not out there because he wanted to be the boss. When they started the bus boycott, they turned to him because they saw a leader there, and he went with it.”

Bonta responded to the call as a voting rights volunteer with Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a civil rights organization established in 1957 following the Montgomery Bus Boycott with Dr. King acting as the first president of the organization. Bonta, along with others, marched in small towns surrounding Selma.

“We would try to march to the center of town to ask for voting rights,” Bonta said. "At one time, we got pretty close to the center of town and armed policemen came up. We did get teargassed, but nobody was severely hurt. On Sundays, we would try to integrate churches in Montgomery. We would be taken by car. They would pair up Black and whites. We would go to the big white churches, and we would try to enter and worship respectfully, and then leave quietly.”

Bonta says he saw Dr. King for the last time during a church service in South Los Angeles in August 1965. Dr. King was supporting Black people following the Watts rebellion, while at the same time encouraging peaceful resolutions.

“The issues that were being struggled over in the 50s and 60s and 70s have not gone away,” Bonta expressed. “We have a major component of our population in this country that has been exploited, segregated and treated worse than just about any other group in the country. One man, in particular, made a stand and organized and used nonviolent action to try to change things and try to improve the situation for Black Americans.”