SACRAMENTO, Calif. — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

At the end of a year in which Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed several bills that would have fundamentally changed how California prisons operate, CalMatters conducted a Q&A with the 2022 recipient of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology, which Stanford University’s Institute of International Studies calls “equivalent to the Nobel in criminology.”

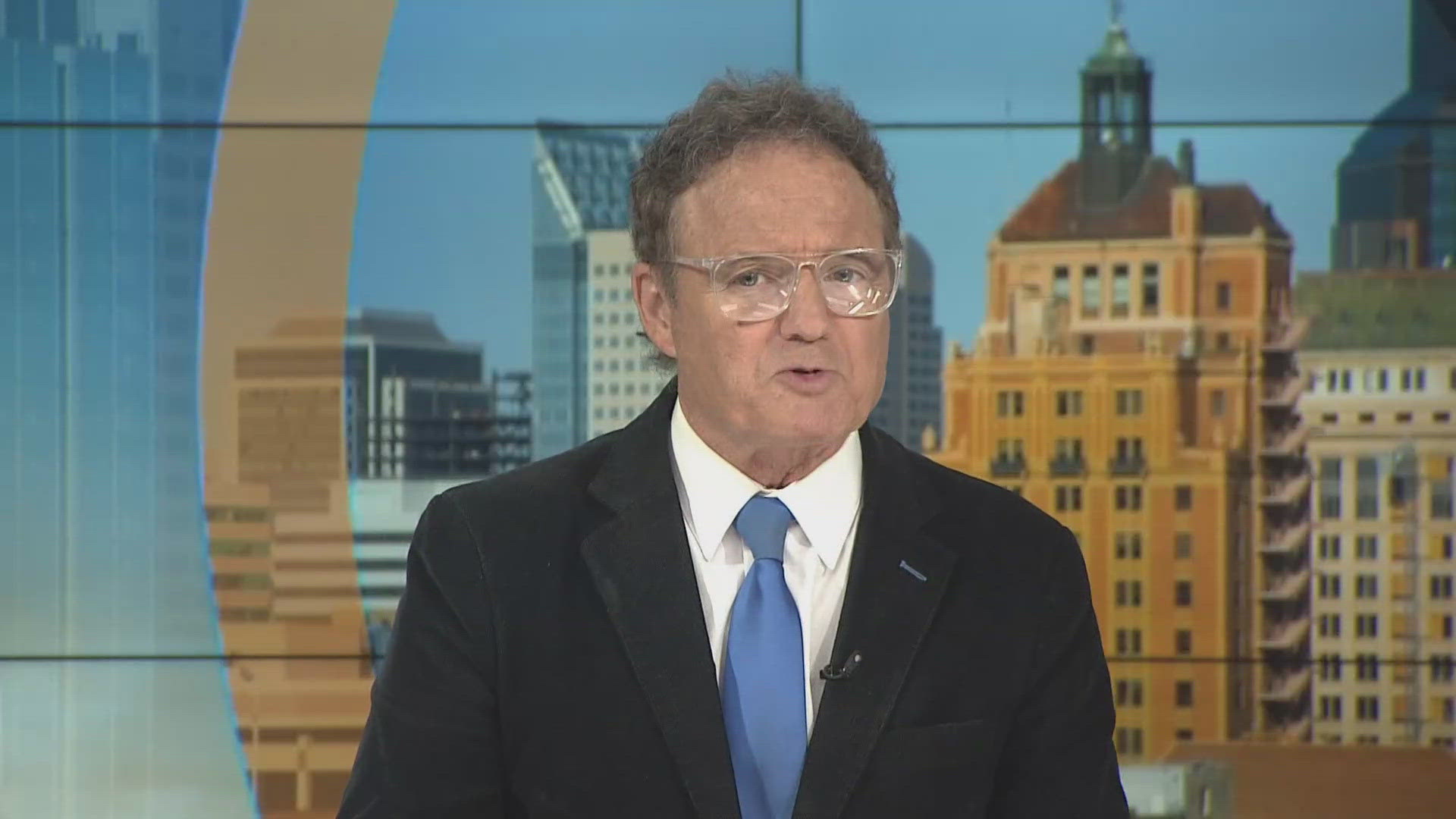

That recipient, Francis Cullen, is a former president of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences, and his research has been cited tens of thousands of times. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has brought him in to address its administrators, particularly concerning community corrections programs.

Cullen discussed how California went from being an international model for rehabilitation to being a cautionary tale. Among his thoughts: This state needs to learn the difference between liberal and stupid.

This interview has been condensed for clarity and length.

Q: The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation — In its most recent update to a federal court mandate that it reduce its prison population — reported that its facilities were filled to 112% of their capacity. Even that is a big improvement over the drastic overcrowding that prompted the order. Can you help put in context how California got into this situation?

A: It used to be the model of prisons in the country. Even when Ronald Reagan was the governor of California, he cut the prison population from about 26,000 to 18,000. They used to have a big treatment orientation, they hired social workers, and basically it was at the forefront of a rehabilitative model of incarceration.

And then in the ‘60s and into the ‘70s, there was an attack on rehabilitation, for a whole bunch of reasons. But the biggest reason is, if you have a rehabilitation model, then you give a lot of discretion to judges and parole boards. In 1976, California … went to determinate sentencing, and basically gave up rehabilitation as a part of their mission. And you gotta understand, liberals went along with that, because they didn’t like parole. They felt the parole boards were keeping in people that were politically active and weren’t letting them out.

(“Rehabilitation” would be added to the prison system’s name in 2006.)

California became punitive with its politics. The things that were done, not just in California, but generally, were all justified on the notion that we want inmates to suffer. The more they suffer, the less likely they will be to reoffend, which actually isn’t true. But that was the logic. And the result, I think, was a disaster. When you get rid of rehabilitation, you take the conscience out of the system.

In California this year, we had what has been called the “Norway Prison Bill,” which would have created a pilot program in prisons, with campuses that resemble the prisons in Norway — prisoners who were chosen could cook their own meals and live in communal spaces while getting job training. Newsom vetoed it along with two other measures related to prisons. His veto message wasn’t that these won’t work. His veto message was we cannot afford to spend the money right now. How do you respond to that assertion?

It was stupid to veto that legislation for this reason: the Norway model works. Now, would it work here in the United States, where you have issues of race and other conflict in prison? We have a different population here, we have racial conflict, we have other issues. But having said that, why not do an experiment?

That is, if you did a Norway unit in our prison, you could have studied it for its effectiveness. Can I say definitively that it would have worked here? No. Do I think it would have? Yes, because the principles make sense.

We have had court cases showing that the medical treatment of inmates is insufficient and the conditions in prison are bad. The recidivism rate is high, and there’s a lot of (probation) revocations. It seems to me that arguing that we shouldn’t spend money is a pretty weak rationale. We spend money on punishment, building prisons and locking people away for a long time. So why can’t we spend money on things that are humane and effective?

The other problem with this is, if you don’t invest in people and they come out and they commit crimes, do people understand the cost of that? There was one study that looked at the cost of, if somebody is a juvenile and becomes a serious offender for a number of years, it’s like $1.3 million dollars.

Not wanting to spend money, when spending money is the only way you invest in people and make them less criminal — it saves money later on. How much is that worth to you?

California had a major prison realignment in 2011. Now, the sheriffs who run county jails say that realignment simply shifted prison populations — and prison politics and prison gangs — into jails. You’ve written, specific to realignment, that “successful downsizing must be liberal but not stupid.” What’s a liberal idea here, and what in your view is a stupid one?

What we’re basically saying by liberal is concern for social justice, not focusing on punishment. An attempt to see that crime is rooted in diverse factors, whether it’s poverty or mental health concerns, rather than saying that crime is just simply a choice, that we need to get tough.

‘Not stupid’ meant that whatever we do in the system should be evidence-based, based on the best science, so the interventions we use should be based on what what criminology has shown works to change people’s behavior.

The question is, when liberals make suggestions about what to do, are they making it based on ideology? Are they making it based on science? Are they looking at the research? Recommending programs that are not rooted in solid science can end up being stupid.

Let’s take bail reform. Now, I’m not against bail reform. There’s some evidence that it works, right? But some bail laws don’t pay enough attention to the risk that people pose. You’ve had problems in San Francisco, where they recalled the prosecutor (former San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who had ended his office’s practice of asking for money bail.)

And maybe that was a bad thing to do. But if you implement bail reform that doesn’t have the support of the staff, that is going to end up letting people out who inevitably are going to commit serious crimes. That’s the kind of thing that can delegitimize liberal approaches. Now bail reform is being attacked all over the country.

So that would be an example of, did they do an empirical investigation of what the effect of bail would be? In other words, you can do bill reform scientifically, or you can do it politically.

Is that what you meant when you wrote, “The failure of past reforms aimed at decarceration stand as a sobering reminder that good intentions do not easily translate into good results.”

Yeah, one would probably be when we decided to pretty much empty and close down most mental institutions, the hospitals for the mentally ill.

We dumped a lot of people onto the street, and didn’t have services for them. And so it was a good thing that people weren’t in mental hospitals, right? But we didn’t create a system to care for those people in the community, so a lot of those people ended up on the street, homeless, in the jail system, in the criminal justice system. And we still haven’t completely dealt with that.

It’s one of the sources of homelessness. It’s not the only one, but that would be the biggest example of when we essentially de-institutionalized a whole bunch of people and then didn’t have any programs to deal with that.

The point is, even today, I mean we do have more (post-prison) reentry programs, but a lot of people we let out of prison, they have mental problems, they don’t have medicine, they don’t have a place to live, they don’t have a job. And it makes no sense to do that.

It seems, in California, that there’s an attitude that nothing works, and nothing will work, to reduce the prison population and improve rehabilitative outcomes. You’ve written about that sentiment in corrections, which you describe as a period of pessimism. Is there a feeling of helplessness when you study this issue?

(Cullen sighs.)

Corrections is sort of like trying to fight cancer. You gotta chip away at it, look for the small benefits. But over 20 years, it can make a difference.

It’s almost like no one whose responsibility it is to change what’s happening is doing anything about it. If no one takes responsibility, then it won’t change. There needs to be almost a social movement, a demand that we do prisons better. Any other business that was run like the prisons would be out of business. They’d be bankrupt.

We do not hold the wardens responsible for the recidivism rates of the people in their prisons. Think about this, okay: If you look at people who are released from prison, which would include both the people who are in for the first time and people in for the second, third, fourth time, you get 50 percent to 60 percent recidivism rates.

If you’re spending that much money and you’re having a failure rate of 60 percent, what does that cost us? Not just the money, but people injured and dying or property damaged? I mean, that degree of failure shouldn’t be acceptable. Think about a hospital where 60 percent of the people die or get worse.

What’s disappointing is that something as small as a Norway experiment can’t even be funded. It’s just gonna lead to a lot of misery inside institutions and a lot of high recidivism rates.

It’s like, you’re California! You should want a return to greatness. You should be the best in the world.