SACRAMENTO, Calif —

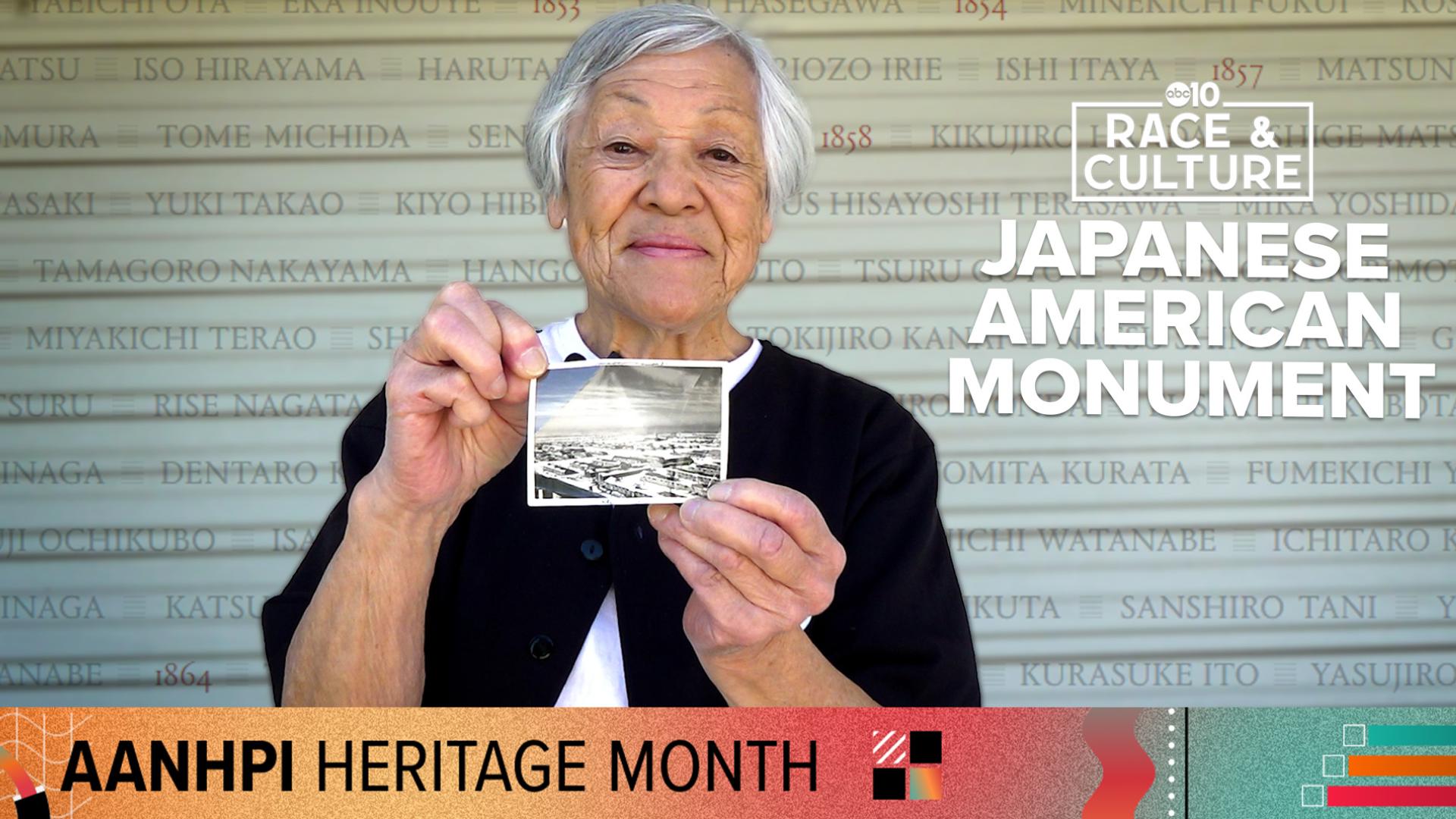

“I think I was ashamed to be Japanese,” said Sachiko Louie, a longtime Sacramento resident.

December 7, 1941, is a dark day for Louie. Japan staged a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu Island, Hawaii. The United States immediately declared war on Japan marking the beginning of World War II.

Months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, at the age of 5, Louie's life changed drastically.

In Feb. 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which approved the “relocation” of Japanese Americans into internment and concentration camps.

Louie and her family were forcibly removed from their Sacramento home and sent to incarceration camps, known as relocation centers at the time.

To honor Louie and Japanese Americans who experienced wartime incarceration from 1942-1945, USC Professor Duncan Ryūken Williams and the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture created the Irei Project, a multi-faceted national monument, in collaboration with a coalition of Japanese American community groups.

“Part of our project is this overarching idea that we are trying to reimagine what a monument to this history can look like,” said Williams.

Traditional monuments are typically large in scale and permanent, he explained, which is what gives it their value, but they wanted to invert that usual understanding by creating something more intimate and interactive.

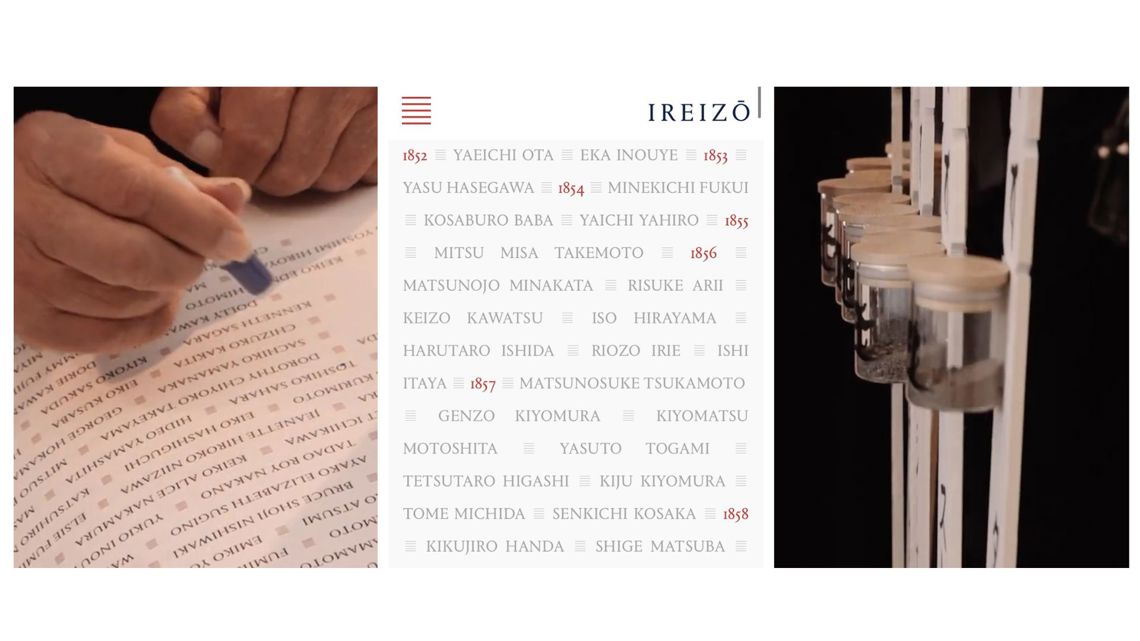

Their national monument has three distinct elements: a sacred book of names containing the first comprehensive list of people of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated (Ireichō), a website listing the names of internees and incarcerees as well as information about them (Ireizō) and sculptures created on the very grounds of incarceration sites (Ireihi).

“Everything has some public interactivity built into our notion of monuments,” said Williams. "I think that's what's maybe particular or distinctive about our project.”

Reverend Shinjo Nagatomi, a Buddhist priest who was interned at Manzanar War Relocation Center, inspired the project. Conducting research for his first book, Williams discovered the reverend’s diaries from camp and the sermons he’d give. There he learned about the Manzanar Ireito or “Soul Consoling Tower,” a monument built by camp survivors and the reverend in 1943 to honor those who would never return home from camp.

“The Manzanar Ireito has become one of the most widely recognized symbols of incarceration,” according to a Facebook post by the Japanese American National Museum.

As a camp survivor, Louie believes the Irei project is also an important tool to acknowledge the nation's dark past.

“It’s part of history that was never written so people don’t know about it,” said Louie. “I have encountered so many people who never knew about it.”

GET MORE RACE & CULTURE FROM ABC10:

►Explore the Race & Culture home page

►Watch Race & Culture videos on YouTube

►Subscribe to the Race and Culture newsletter

The project was particularly focused on identifying the exact amount of people who were incarcerated and where.

“One of the things that has been baffling researchers and scholars in the major institutions that do work on the Japanese American incarceration is how many people experienced the forced removal and unjust incarceration and numbers range from 100,000-200,000,” said Williams. “Our project was to solve that.”

His team carefully documented incarcerees using the National Archives and other government-created camp rosters, train transfer lists and internee cards to cumulatively do the work of naming each person.

They found 125,284 individuals were held in 75 camps.

The public can access the list online where there’s also photographs, mail letters and oral histories tied to each person, thanks in part to a collaboration with community organizations. Recently, they partnered with genealogy company Ancestry to help Japanese individuals find their family history and explore the other record collections from this period.

Williams said this partnership allows people to see “who [a] person was before the war as well as after the war.”

Overall, the project wants to ensure no one is left out, misspelled names on government documents are corrected, and that beyond remembrance they are helping repair the historical record.

For Williams, repair is an important aspect of the national monument project. As a Buddhist priest, he believes in the idea of karma: an action has either a positive or negative consequence. He said this doesn’t just apply to individuals but to communities and even a nation.

He believes the monument project is helping reckon with the racial karma of the United States during that time period.

“If we don't attend to that karma, if we don't actually try to reckon with it, try to repair some of this harm that's been done in the past, then we're actually just letting it kind of continue on,” said Williams. “This is our way of interacting with the past and by so doing, every American, not just camp survivors and descendants can be involved in an act of reckoning and repairing this history.”

You can access the list of names online HERE.

ANOTHER AAPI HERITAGE MONTH STORY YOU MIGHT ENJOY: How a UC Davis law professor discovered the oldest Chinese restaurant in America.