RALEIGH, N.C. — Descendants of slaves removed from Africa to clear swamps for a North Carolina plantation are holding a reunion at the site, with some spending the night in a reconstructed slave cabin.

About 40 descendants of two slaves named Kofi and Sally planned to gather Saturday at the Somerset Place State Historic Site , a former plantation in Creswell in eastern North Carolina. Six family members are among a group staying overnight on the grounds.

Mina Wilson, 57, of El Cerrito, California, is one of those spending the night as part of the Slave Dwelling Project.

"I think it will be a deeply spiritual experience," she said. "I think we'll be talking and communing with the energy there."

Kofi and Sally were brought to Creswell from the coast of west Africa along with 78 other enslaved people, arriving in 1786, said Karen Hayes, site manager for Somerset. The swampland had to be drained and cleared of century-old trees before crops could be planted, and the slaves did the back-breaking work in North Carolina's heat and humidity.

They first spent two years digging the six-mile transportation canal connecting Lake Phelps to the Scuppernong River so people, crops and equipment could be moved. The canal is 20 feet wide and up to 12 feet deep.

"They were dealing with mosquitos, snakes and heat exhaustion," Hayes said. "And they didn't know why they were here and why they were captured."

Those who collapsed on the side of the canals were left there by white overseers and then buried in the morning, she said. In an 1899 book, a former Somerset overseer said that the slaves would drown themselves to escape bondage and some died from the work.

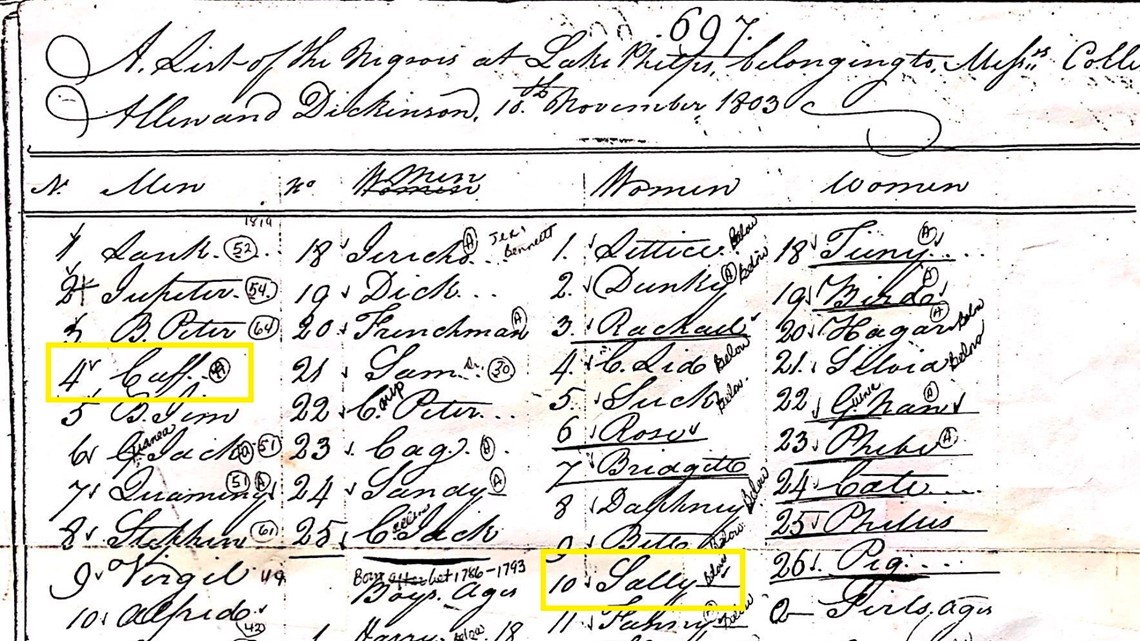

In an indication of mortality among the slaves, just 15 of the original 80 are identified on the 1803 slave inventory, according to genealogical data gathered by Dorothy Redford, former executive director of the site.

The below image is an undated photo made available by the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. The list from Nov. 10, 1803, shows the slaves at Somerset Plantation in North Carolina, among them the names of Sally and Kofi (listed as Cuff).

By 1865, Somerset had expanded to include thousands of acres of crops, along with sawmills. The number of slaves working the property grew to more than 200.

The main house, built about 1830, still stands while the original slave cabins did not survive. The two there today were built at the same location as the original ones, to the same size and using the same materials, Hayes said.

No slave descendants have ever spent the night there, Hayes said. The descendants are among 18 people staying on the grounds Saturday night.

The larger group includes Joseph McGill, who began the Slave Dwelling Project to emphasize the history of slaves. As part of that project, descendants of slaves have previously stayed at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and at James Madison's Montpelier in Virginia.

McGill, who said he has stayed overnight in slave dwellings about 200 times, said the project is about awareness for him.

"But for the descendants of those enslaved, it's totally different," he said. "It's making that connection. It's rare that African Americans can make those connections to the place where their ancestors were enslaved...they still have to get over the anxiety of visiting the place where their ancestors were enslaved."

It's a story that was new to Wilson when she got a package from Redford years ago telling her that she had descended from slaves — part of the sixth generation of Kofi and Sally. That story gives her "a different level of appreciation for the journey my parents and their parents took, and the vision they had to lead themselves from that to where I sit," she said. "I have an immense gratitude and appreciation for that."