KLAMATH, Calif. — Before the dams were built, before the trees were logged and before the fish were blocked from going upstream, the Klamath River was a highway for redwood canoes. The Yurok were not the only Native American tribe to navigate the Klamath, but they were among the last.

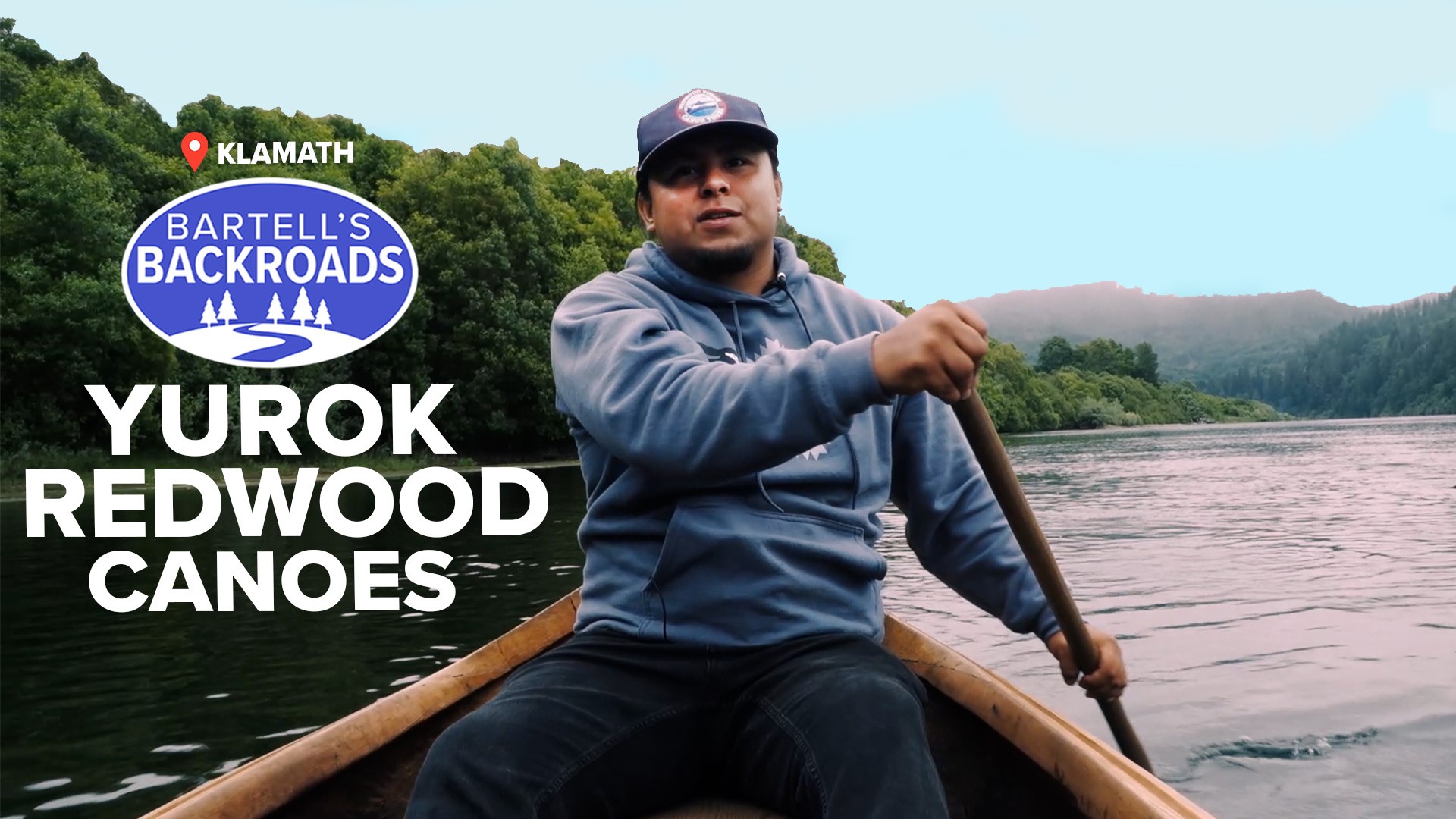

Normally, Julian Markussen wouldn’t be taking tourists for a ride in a Yurok canoe. The Ohl-we-yoch (Oth-way-otch), as they're called, are sacred vessels. Last year, the tribe had a change of heart and started offering the public two-hour tours down the Klamath.

“You can’t have people respect you if they don’t know who you are,” Julian Markussen says. “There’s only about 11 of these in existence, so this is one of the rarest vessels in the world right here.”

The Yurok people were once great canoe builders, but if you ask around on the reservation today, there’s really only one man carrying on the tradition: David Severns.

“I learned to build them 14 years ago and I’ve been around them ever since,” says Severns, who was about 50-years-old when he started to build canoes. Today, he can count the number of experienced builders on one hand.

“Our goal is to keep our kids out of trouble through culture and teach them to build canoes,” Severns says.

He uses a mix of modern and ancestral tools to teach canoe building, but the most important part of a Redwood canoe can't be found on the reservation.

“The tribe doesn’t own big timber. That’s been taken away by timber companies or lost through mismanagement of the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Severns says.

The centuries-old redwood logs needed to build a Yurok canoe must be acquired from government or private land. Either way, transporting the log to Yurok country is very expensive.

“So, the opportunity to keep doing this is solely coming from the tourists taking those rides. It’s sad but it’s important for us,” Severns says.

Old growth redwoods were once abundant along the Klamath, but as the Yurok were pushed off the land, sawmills and fish canneries took their place. They also took the resources the river provided.

Markussen gestures to the trees lining the shore of the river. “All along the banks, those silver-barked ones are alder trees,” he says.

As Julian paddles along the bank, he explains the river is in a constant state of healing itself. "When everything was cut down, [alder trees] were the first to grow back, so they earned the nickname 'scab of the woods.'”

Another wound the alder trees are growing over is damage from the Christmas flood of 1964. Considered to be one of the worst floods of its time, water wiped out roads, homes and many of the industries in the area. Even the Yurok experienced major loss.

“All the canoes, a couple dance sites and older buildings,” Markussen says.

Months later the same year, a tsunami hit Crescent City -- the largest city the area. The massive wave slammed into downtown, devastating 29 city blocks leaving hundreds of people homeless.

“After that, everyone cruised out of Klamath and kind of gave the land back to the Yurok.”

While the land along the Klamath is healing, the water is still sick. “The dams are the biggest culprit of making the river sick,” Markussen says.

Five hydroelectric dams slow water from the Klamath. In years of drought, plumes of blue-green algae grow in slow moving water. In 2002, the algae caused a massive fish kill by suffocating tens of thousands of salmon and other aquatic life.

“It seemed like the end of times, really, and it sparked a movement and made us realize we need to do something now,” says Markussen.

For more than 20 years, the Yurok, other Native American tribes, and conservationists from all over the state fought to restore water flows in the Klamath. Thanks to those efforts, the complete removal of four out of the five dams will begin in 2024.

“300+ miles of habitat will be restored back to balance and brought back to its natural habitat,” says Markussen.

The Klamath River is in a constant state of healing itself, but instead of showing tourists how sick the river is, the Yurok hope to show what happens when the river is cared for.

If you want to take a canoe tour with the Yurok, schedule your reservation here.

HIT THE BACKROADS: Summer is here! Plan your ultimate road trip with John Bartell's list of California's top 10 destinations to visit.