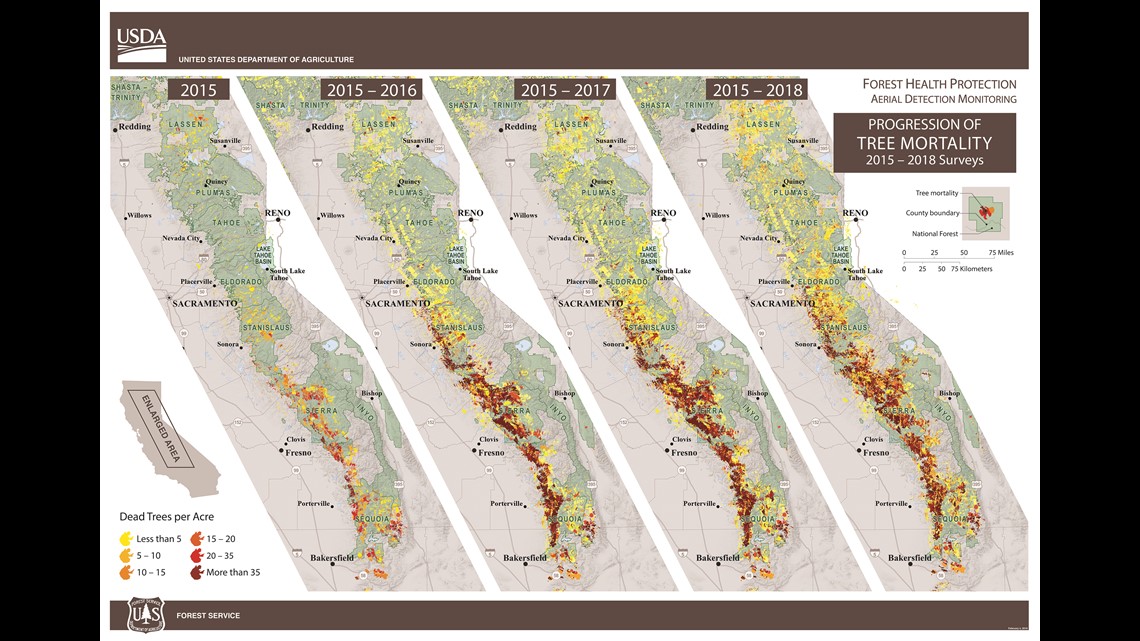

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Every year, the United States Department of Agriculture surveys California's forests. Government and private forestry staff take to the skies in various aircraft to sketch out maps of the state's dying, defoliating and damaged trees.

And every year, the data they compile from these observations show that more of California's forests are dying. This year no different.

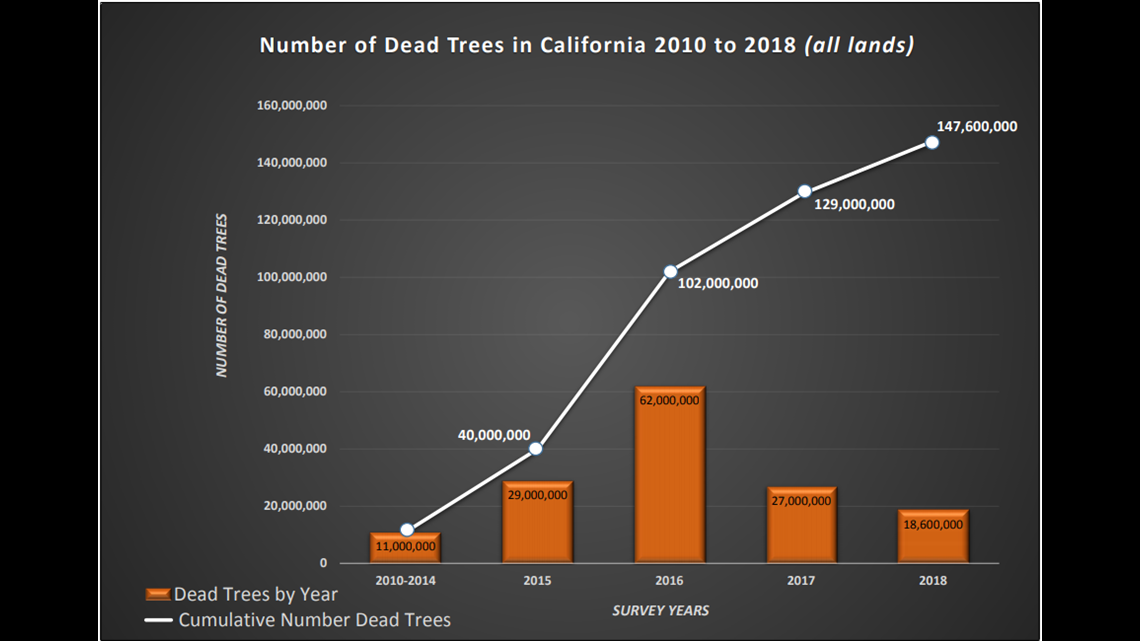

Over 147 million trees have died over eight years

The numbers from the 2018 USDA Forest Health Aerial Survey released in February show that 2018's below average rainfall slowed the forests' recovery from drought and diseases.

And even heavy rain and snow totals in the first few months of 2019 might prove to be detrimental to forest survival. According to the ecologists who compiled this year's Forest Health survey, the end state-wide of California's drought is expected to be a breeding ground for the fungus responsible for Sudden Oak Death.

Over 147 million trees in California forests have died over the last eight years. Most of these forests are near the southern Sierra Nevada, which shows an increasing threat to iconic California landmarks like the Sequoia and Yosemite national forests.

Despite the end of droughts and superblooms, California is still high-wildfire risk

So while the rains and snowpack create beautiful superblooms and end multi-year droughts across the state, California's trees continue to die and pose a problem for future wildfires.

Another new study with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration focuses the North Pacific Jet Stream (NPJ), high-altitude winds that blow across the Pacific Ocean into California and are responsible for the majority of water deposited across California, and its relation to California's climate and wildfire risk.

For over 400 years, according to the study's paleoclimatological data, the NPJ's amount and intensity of moisture have indicated whether the state would be in a low or high-fire year.

But as of 2017, a year with both above average rainfall and above average fires, including the Tubbs and Thomas fires, that link is no longer accurate.

"Besides fire risk and its associated health and economic impacts, such a change could alter species distribution, forest composition, and ecosystems," NOAA stated in their news release of the study.

Record rain won't solve California's fire problem

California officials have been starting to realize the gravity of the deteriorating health of California's forests only recently. Last year, Governor Brown implemented the Forest Management Task Force as an executive order as a counterpart to the Tree Mortality Task Force. And earlier this month, CAL FIRE submitted their report to Governor Newsom to identify the most vulnerable communities to wildfire and the projects that could protect them. This week, the Capitol hosted the first ever Wildfire Technology Innovation Summit to address the growing wildfire risk with stakeholders across a spectrum of industries.

There are several tools residents can also use to educate themselves on the increasing danger that surrounds them. There's the Tree Mortality Viewer, a live map of the areas most impacted by forests deaths, and therefore the at the highest wildfire risk. And there's ALERTWildfire, a system of live cameras where viewers can alert officials if they think they spot a fire on one of the cameras. ALERTWildfire recently implemented 88 additional cameras this month.

So while the drought may be over, Californians cannot be complacent until the next wildfire starts.