ELK GROVE, Calif. — A few years ago, Gina McVey of Elk Grove discovered a piece of world history in her family’s past. It all started with a chance encounter at a car dealership.

“There was a gentleman in military uniform and we were both sitting in the waiting room. So, as we’re sitting there I told him, ‘Thank you for your service,’” McVey said.

In the conversation that followed, McVey mentioned that her own grandfather had fought in World War I, and left her family “a French medal” he had won. She said the man perked up and asked if the medal could possibly be one called the Croix de Guerre. When she confirmed it was, she said the man replied, “Do you know what you have? You have history.”

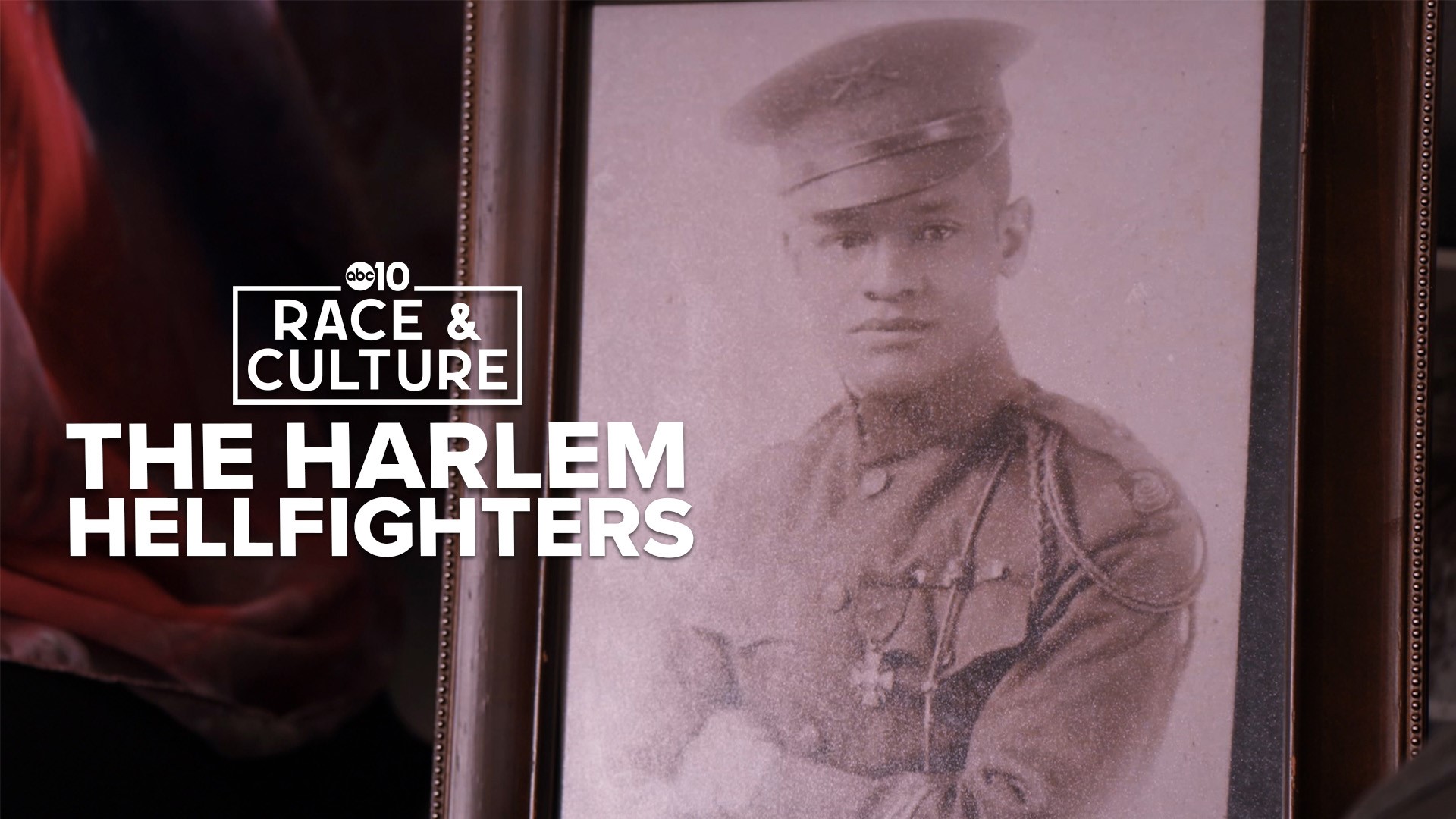

The Croix de Guerre was a high honor in the French military, recognizing exceptional bravery in combat. Gina’s grandfather Lawrence Leslie McVey was one of the few African American men to ever receive the medal.

Lawrence McVey’s story began in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, where he grew up. He came of age during the first World War.

At the time, Black men were allowed to serve in the United States Army, but only in segregated units. Lawrence McVey was drafted into Harlem's 369th infantry, a regiment that would come to be known by many names. To themselves, they were the “Black Rattlers.” The French called them the “Men of Bronze.”

But there was one name that stuck.

“The Germans were the ones who called them the Harlem Hellfighters,” Gina McVey said, “because they were scared of them.”

So, why were these Harlem Hellfighters serving under the French military?

France had been fighting in World War I for several years before the United States intervened in 1917. By that point, France was devastated, and asked the U.S. General John Pershing for reinforcements. Pershing agreed to send the segregated African American units.

A memo titled “Secret Information Concerning Black American Troops,” signed by a U.S. colonel serving under Pershing, reveals the U.S. military’s attitude toward its Black soldiers at the time.

It called Black soldiers “inferior” to whites, and said they lacked “civil and professional conscience.” It gave instructions to the French military on how the U.S. expected its Black soldiers to be treated, saying among other things: “We must not eat with them, must not shake hands or seek to talk or meet with them outside of the requirements of military service.”

France’s military was not segregated like that of the U.S. Despite the warnings in the “secret information,” African American soldiers were trained and fought side-by-side with their French counterparts. Instructions to “not commend too highly the Black American troops” were particularly ignored, at least in the case of the Harlem Hellfighters, who as a unit were awarded the Croix de Guerre.

According to the Smithsonian, the Harlem Hellfighters fought the longest and lost the most men of any U.S. unit. They spent 191 days on the front lines and lost 1,400 men. After the war, they were all awarded the Croix de Guerre, but Lawrence McVey won his medal earlier in the war.

“My grandfather received his Croix de Guerre because he led his troops against a nest of German machine gun fighters until he was wounded,” Gina McVey said.

At the end of the war, Lawrence McVey and the Hellfighters came home decorated in honors from France, but their own country still refused to treat them as equals. Black soldiers returned to the same segregation and discrimination in the United States that they experienced before the war.

Despite their distinguished service, it took the urging of one of their white captains to secure the Harlem Hellfighters a victory parade on February 17, 1919. Nevertheless, photos and film strips from the National Archives show a joyous occasion as the Hellfighters marched down Fifth Avenue in their home neighborhood of Harlem in New York City.

“You just see people dressed to the nines celebrating them,” Gina McVey said of the images. “And that was the only celebration that they received.”

Lawrence McVey held on to his Croix de Guerre for years. Eventually, he passed it down to his family, along with other memorabilia from the war.

When Gina McVey realized the importance of what her grandfather left behind, she contacted the 369th Armory in Harlem, which was built after World War I for her grandfather’s regiment, but they didn’t have the capacity to take everything that the McVey’s had saved.

She decided to try the Smithsonian, which just so happened to be making preparations for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Gina happily gave them everything she had: her grandfather’s pictures, uniform, rifles, and the Croix de Guerre. They’re all displayed there today, a monument to his life.

“It’s to let everyone know that we are important,” McVey said about the importance of sharing her grandfather’s legacy. “We have fought for a country that didn't fight for us. We believed in you when you didn't believe (in) us. So to me, it's my way of saying thank you.”

WATCH ALSO: Sacramento man made history as one of the first African Americans inducted into the U.S. Marine Corps.