Segregating Sacramento: How racial agreements shaped neighborhoods and quality of life

The Sacramento region is built on race covenants that prevented people of color from living or purchasing property in certain neighborhoods.

ABC10/KXTV

Part One

It's well known that the neighborhoods people live in can dramatically determine their quality of life. Access to a higher standard of education, healthcare or fresh fruits and vegetables can vary hugely from neighborhood to neighborhood.

A Sacramento urban sociologist discovered the root of the problem in the region and says it has to do with a racial divide and inequality.

“I started comparing it to everything, like education and housing and health and all the social ills wound up in this north-south pattern of race and poverty,” says Jesus Hernandez.

Hernandez has a PhD from UC Davis and over 30 years in the real estate industry.

He has dedicated most of his life to studying and understanding social problems that affect neighborhoods and quality of life. His passion came from his own experience of being born and raised in Oak Park.

“It was pretty much the worst place in the county, and I can remember that in third grade that I wanted to study why this happened and how did this come to be?” Hernandez said.

Hernandez gave ABC10 data to compare neighborhoods in census tract 28, Oak Park, to census tract 24, Land Park.

In Land Park, the median household income is $141,000 and in Oak Park the median household income is $44,000.

In Land Park, nearly 70% of people have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and in Oak Park, it’s 17% who have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In Land Park, the median net worth is a little over $859,000, and in Oak Park, it is $20,000.

The Oak Park area was one of the hardest hit in the recession between 2007 to 2010, also known as the subprime mortgage crisis. People lost their homes.

Unfortunately, those people do not live here anymore because of foreclosures,” Hernandez said. “You see this transfer of property going from poor people to investors. Now, there’s only 33% homeownership in this neighborhood.”

Hernandez traces back the stark difference between neighborhoods to race covenants.

The real estate industry played a significant role in housing segregation, not just in Sacramento, but across the nation.

As our cities began to grow, restrictive covenants became a way for city planners and real estate developers to implement their planning and design visions.

Race covenants controlled who could live on a property.

Beginning in 1913, the National Association of Real Estate Boards instructed its members not to contribute to race mixing through property sales and provided their members with templates for race covenants to use in new home construction.

This is an example of one dated 1941 from South Land Park.

It states “neither the whole or any part of said premises shall be sold, rented, or leased to any person or persons not of the white or Caucasian race.”

Race covenants were justified as a way to protect property values, and it became a way to create distinction and distance from what was perceived as less desirable residents, meaning people of color.

For almost half a century, race covenants were written into property deeds.

“East-west is where I tracked the pattern of race covenants, racially restrictive covenants, deed restrictions on property that limited the ownership to White people or members of the Caucasian race as it's put on the deed restriction, so that you see this east-west pattern of affluence and this north-south pattern of racial concentration and poverty, and that's how you get the X,” Hernandez said, referring to the "X" he uses to describe areas of the Sacramento region impacted by race covenants.

The neighborhoods he refers to in the north and south parts of Sacramento include North Highlands, Oak Park and many in South Sacramento.

The neighborhoods in the east and west include Land Park, Curtis Park, East Sacramento and Arden Park.

Neighborhoods where people of color could not live had decades of preferential treatment.

“Land Park was one of these neighborhoods, especially this park here helped us get out of the Great Depression,” Hernandez said. “You put all this public money into it, building parks, building ball fields, building the golf course.”

Land Park and other neighborhoods with race covenants enjoyed the benefits of parks, public transportation and even an abundance of trees.

“As these trees mature, so do the neighborhoods,” Hernandez said. “The values in these neighborhoods grow and because they had that public investment. You look over here, they build Sacramento City College, so it has all the tools it needs to thrive. This is the kind of public investment we’ve been putting into neighborhoods for decades.”

Based on Hernandez’s research, the neighborhoods that had race covenants were not only wealthier but healthier. Data shows fewer cases of asthma and even COVID-19 compared to the neighborhoods to the north and south.

Local developers used race covenants as late as 1960.

However, by that time, Sacramento was already shaped, and established neighborhoods defined by a lack of investment in some areas suffered.

“We pull money out of those neighborhoods and put it into other neighborhoods, so when you devalue the places where people live, you actually devalue the people,” Hernandez said. “When you do that, that's how you create these biases that are so hard to undo today. So, rather than look at the processes that created that, we look at the people, which makes it even worse."

Hernandez’s research is highlighted in a report that can be found here.

Part Two

The West End of Sacramento was an area west of the Capitol.

Sacramento residents and friends Marian Uchida and Amy Kamikawa Wong remember it as children.

"It was a nice community," said Uchida. "It was a mixed community."

The West End was the first thing that you saw entering Sacramento off the Tower Bridge, before the highways were built.

Several communities were there including Japantown.

"I remember everything about it because I lived right in there," Kamikawa Wong said. "My dad was a plumber, and so we lived right in the heart of Japantown."

By 1940, there were nearly 4,000 Japanese residents and hundreds of Japanese businesses such as banks, hotels, schools, and churches.

After World War Two, Japantown became a place of opportunity for Japanese Americans who had been forced into internment camps.

"When we came back from camp, because they couldn't own property, they had to learn English and a lot of the churches in Sacramento had English classes, and then they had citizenship classes so they can get their citizenship so they can buy property," Uchida said.

The West End was an area where people of color were allowed and accepted.

It became the port of entry for labor.

"It was probably the largest Japanese-American community on the West Coast, just concentrated in that one particular area," said Clarence Caesar, retired historian with the state of California. "It also included African-Americans, Latino Americans as well."

The West End was a vibrant cluster of ethnic enclaves but it was the oldest part of Sacramento--and the poorest.

Property owners couldn't get loans to make repairs or improvements because of government sponsored mortgage redlining policies that prohibited loans in racially integrated neighborhoods.

The West End was considered risky for lenders mostly because the area had a high concentration of people of color.

The city saw the West End as an opportunity to revitalize.

Even though voters shot down the idea in the 1950s, that didn't stop the city from moving forward with their plans.

"They basically developed a model, a model by which they could determine the area blighted and they could basically sever all tax revenue that came out of that area," Caesar said.

For the Japanese American community, it meant leaving once again, abandoning the place they called home, seeing their culture turned into rubble.

Redevelopment and freeway construction started in the mid 1950s. Minority residents were forced to move from the West End to neighborhoods that had no race covenants.

For almost half a century, race covenants were written into property deeds to prevent people of color from purchasing or living in Sacramento’s affluent all-white neighborhoods. Race covenants were enforced to protect property values and became a way to create distinction and distance from what was perceived as less desirable residents, which meant people of color.

Most of the people who had to leave moved to the north and south parts of Sacramento such as Oak Park, Del Paso Heights, and South Sacramento.

People lost their jobs, their businesses, and their homes.

The gateway to Sacramento changed.

Sacramento's civic leaders were proud of the work they had done to redevelop an area they considered less desirable to live in, all through an innovative financing method known as tax increment financing which uses future tax revenues to match federal funding...a tactic that became a model throughout the country.

Before redevelopment, minorities were able to find jobs using their West End connections. After they were displaced, they no longer had access to those contacts that kept them employed.

Many businesses had to close because they no longer had the support of their community or couldn't afford the higher rents. It's estimated about 8,500 people had to leave the West End because of urban renewal projects.

Part Three

One of the areas people moved to when the West End of Sacramento was cleared for revitalization was Oak Park.

Joe Debbs, a Sacramento resident, grew up in Oak Park.

"I've been here [for] all intents and purposes a lot of my childhood and adult life," Debbs said. "It was hustling and bustling. There were a lot of people. There were businesses. It was diverse. It almost reminded you of the Harlem renaissance."

Oak Park is Sacramento's oldest suburb and was developed in the late 1880s. It started as a working class neighborhood with European immigrants.

By the early to mid 1900s, 35th Street was a popular shopping area functioning as a regional business center serving residents from Curtis Park, Land Park, McKinley Park and other areas before the highways were built.

Ginger Rutland, a Sacramento resident, spent a lot of time in Oak Park with her family.

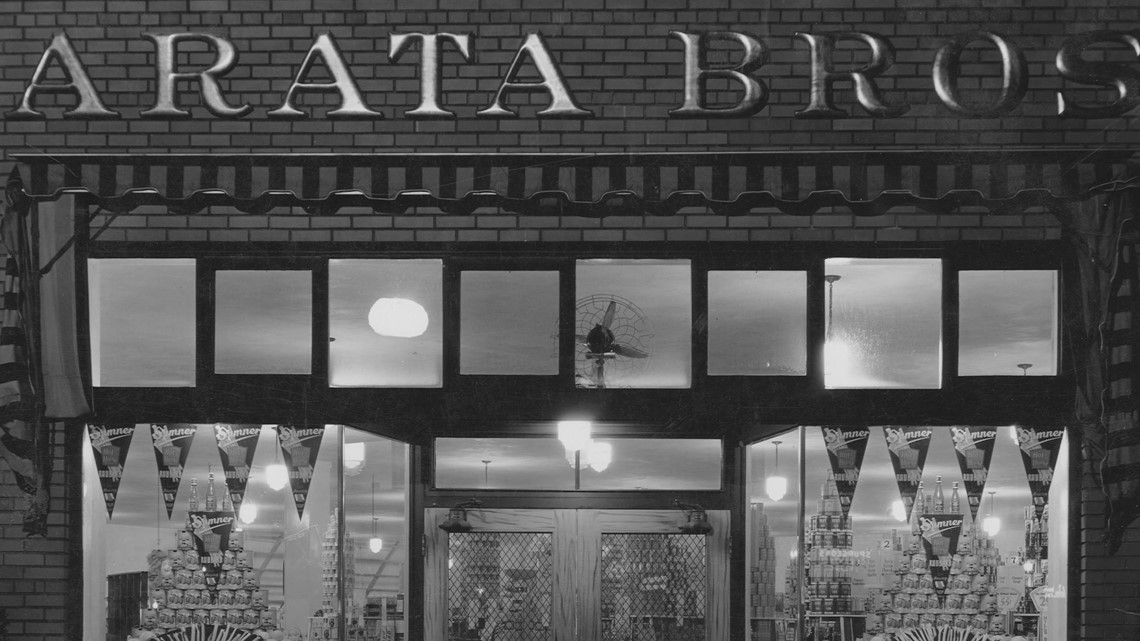

"There was a grocery store there called Arata Brothers and that's where mom did the family shopping," Rutland said. "There were dress stores. It was lovely."

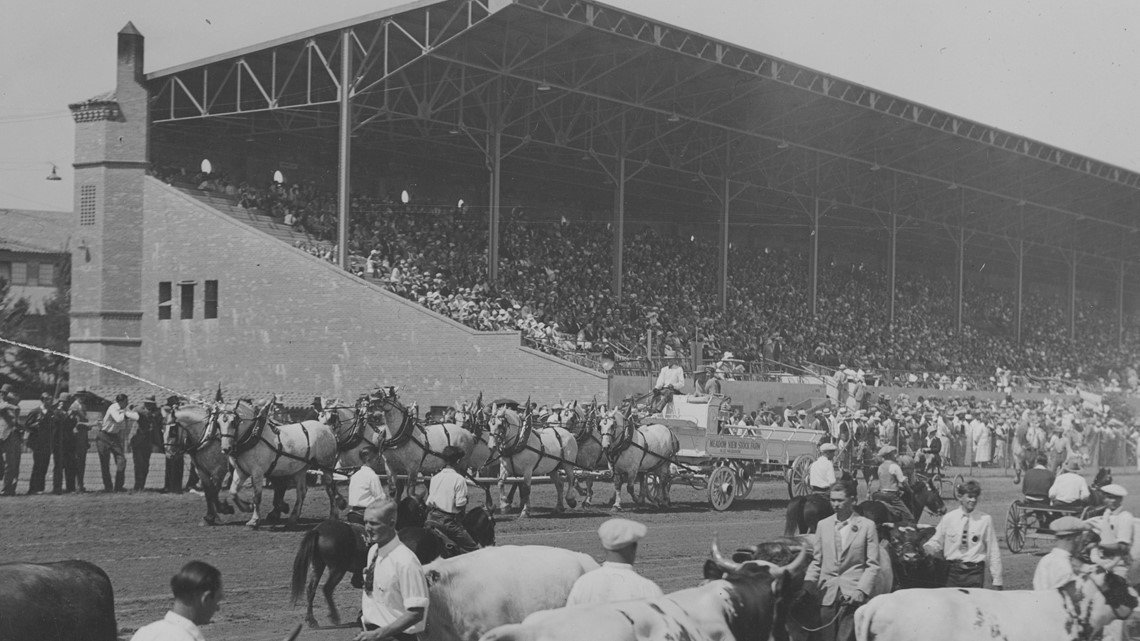

Before Cal Expo, Oak Park was home to the State Fair.

"It was something you looked forward to every year," Rutland said. "It was beautiful. There were these beautiful old brick buildings. They had a race track."

Then, Oak Park started to change in the mid 1900s.

As the West End of Sacramento was cleared for redevelopment, it displaced thousands of people of color. One of the few options they had for finding a place to live was in Oak Park since it didn't have race restrictions: neighborhoods with race covenants did not allow people of color to live in or purchase homes.

As a result, this movement of non-white residents to places without race covenants resulted in new concentrations of people of color in places like Oak Park, Del Paso Heights, and Glen Elder.

"It was easier for them to move there and so they moved there in greater numbers and by 1960, Oak Park had like the second largest Black population census tract after Del Paso Heights," Clarence Caesar, retired historian with the state of California, said.

Oak Park started to experience a lot of changes during this time that some say would lead to its downfall.

"They built 99 on the Curtis Park side of Oak Park, and then Highway 50 cut Oak Park off from the very affluent East Sacramento. So, Oak Park was wedged in this triangle," Rutland said.

After the highways were built, in 1967, the California State Fair moved from Oak Park to Cal Expo in the Arden Arcade area. People didn't need to go through Oak Park to shop and it forced businesses to close.

The impact was devastating for the community; many stores closed and people lost their jobs when the fairgoers stopped going to the area.

"Many of the people worked there," Debbs said. "Parents had jobs working in the stands as clean up folk."

In addition to these changes, California was going through a major budget crisis and Gov. Ronald Reagan cut funding to health services like mental health and welfare programs.

"Oak Park now became the center for all of the problems from the West End," Jesus Hernandez, an urban sociologist, said.

Civil unrest in the 1960s was also centered in Oak Park.

The headquarters for the Black Panthers, a neighborhood activist group, was on 35th Street. On Father's Day in 1969, police raided the headquarters. Hernandez said news coverage at that time instilled fear and made businesses move.

"This was a period of time where the concept of race was a fear factor, and so there was this public fear and how we reported things was actually stoking that fear," Hernandez said. "We reported the Black Panthers as people of violence and I actually went to their breakfast programs when I was a kid and there was voter registration stuff going on, so I didn't see that fear side."

Some say the riots after the Father's Day raid destroyed what was left of the business district on 35th Street.

"When I came back to Sacramento in 1971, Oak Park was a sad place," Rutland said. "Most of the businesses were gone. It had just deteriorated. The businesses were boarded up. Thirty fifth, which had been this vibrant shopping area, was no longer there."

Although some say the area will never fully recover from the divestments made over that 20 year period, there has been changes in the last few years. New shops and trendy restaurants reminder people of what Oak Park used to be.

"I've seen the good, bad, and ugly come through here, and to see Oak Park being revitalized, I have no problem with it because when you have a healthy community, then you have jobs and then you have people who are trying to make it. Public safety comes into play," Debbs said.

But with these new businesses and new life it's also pricing some people out. It's something Debbs is worried could happen to his family.

"I wish everyone the best but not on the backs of people who can't afford to not do any better," Debbs said.

Part Four

For more than a century, decisions based on race shaped Sacramento’s neighborhoods and how they look today.

Decisions such as where people were allowed to move and where schools and parks were built.

“We need a lot in our neighborhood,” Latisha Perry, a Sacramento resident, said.

Perry lives in South Sacramento by Fruitridge Road and Franklin Boulevard.

“When you go to other areas they have all these stores, but over here you don’t have that much," Perry said.

Currently, Perry is taking a free Digital Literacy Class a block from where she lives at La Familia counseling center. The organization offers free programs and outreach services.

“People want the opportunity to work,” said Rachel Rios, La Familia Counseling Center Executive Director. “They want the opportunity to learn. They want the opportunity to get into housing to better their families, to better their situation.”

The neighborhood where La Familia Counseling Center is located in South Sacramento is called North City Farms. It has seen the impacts of disinvestment. In 2013, Sacramento City Unified School District made the decision to close seven schools due to low enrollment.

A majority of them were in the South Sacramento region.

La Familia Counseling Center is located at what used to be Maple Elementary.

“When the school closed, we did a survey of the community and the kids were sent to 16 different schools,” Rios said. “Because they were bussed they couldn’t participate in the after school enrichment programs. They couldn’t join clubs.”

The impact of closing schools is more than just bussing students around. It’s a neighborhood that loses money.

“School funding is basically based upon the students and where the student goes. So, if you move the student, that money goes with that student. So, if you move, you close the schools in the poorest of neighborhoods and you open up schools in the richest neighborhoods, that money goes to those neighborhoods and those neighborhoods thrive,” Jesus Hernandez, urban sociologist said.

This neighborhood is one of many in Sacramento that started without race covenants. Hernandez has dedicated most of his life researching how it happened and why.

Neighborhoods with race covenants saw all the benefits of parks, schools, and public transportation while neighborhoods without race covenants got left behind.

“There are no health services in this area,” Rios said. “We don’t even have transportation. Public transportation doesn’t come all the way through here so people have to walk a great distance on a street that’s not shaded. So, just your basic infrastructure is missing. On top of that, you add the support services that make communities thrive. Libraries all of those things. Those don’t exist here.”

According to Hernandez’s research, the neighborhoods without race covenants — which are mostly the north and south parts of the city — have a higher unemployment rate, more cases of COVID-19, and have more health issues like asthma and cardiovascular disease.

They are also less likely to be homeowners compared to neighborhoods to the east and west that had race covenants.

An organization trying to change that is Habitat for Humanity. They’re helping people become homeowners through volunteering and financing.

“The north and south parts of the city are traditionally the most underserved regions of our area, at least within the city of Sacramento,” Shannin Stein, Habitat for Humanity of Greater Sacramento Chief Development Officer, said.

Habitat for Humanity turns empty lots into communities. They’re currently working on a project in South Sacramento.

“When we build in the area, we’re creating homeownership opportunities and that directly contributes to the county tax roll, and so it creates investment opportunities into schools, into roadways, into parks that are generated through homeownership taxes,” Stein said. “It is also a long-term investment.”

Organizations like Habitat for Humanity and La Familia Counseling Center are trying to fill the void of nearly a century of disinvestment.

“When you take away the factors that help you create income, or you racialized them, they are not going to be in these poor neighborhoods. Then you see, that's where you see this disparity happening, and this is really important because if you don't have income, you can't buy a house. You can't send your kids to college,” Hernandez said. “You don't earn that equity and the intergenerational wealth doesn't happen.”

The city of Sacramento is aware of the data and more that’s highlighted in a report by Hernandez.

With the assistance of his report, Senate Bill 1000 would require cities and counties to include environmental policies to help disadvantaged communities.

“The intent of the law is good. How we actually implement the law is different, and whether cities actually have the capacity to do what's necessary to really roll out legislation fairly,” Hernandez said.

This report is supposed to help the city finalize their 2040 general plan, a guide for the future. Some of the city's top focuses include ways to reduce car use, revitalize commercial areas, and even plant more trees.

The process has been years in the making and they will decide on the final plan this spring.

► Get more stories about race and culture: Sign up for our newsletter at www.abc10.com/email and find more online in our Race & Culture section.

WATCH ALSO: