Juneteenth: The life of a former slave with Sacramento family ties

Peter Hunt was born into slavery in Amite County, Mississippi. He's the son of America Hunt, a Black female slave, and Captain Henry Hunt, a white male slaveowner.

The origins of Juneteenth Fighting for freedom

Juneteenth commemorates the end of slavery in the United States. It’s also called Emancipation Day, Juneteenth Independence Day, or Freedom Day. It’s observed annually on June 19. The name "Juneteenth" combines the words "June" and "nineteenth" to mark a historical date.

"On June 19th, 1865, a Union general named Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas to read a proclamation called Order No. 3 to inform the good people of Texas that as per the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, all enslaved people were free,” said Dr. Elisa Joy White, Associate Professor of African American and African Studies at UC Davis. “It let people know that there would be an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and former slaves. It said you will now have an official relationship between former master and slave as employer and hired labor.”

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, more than 250,000 slaves in Texas had a right to freedom. The message, however, came more than two years after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the U.S. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, except as a punishment for crime, in 1865.

The Proclamation was intended to cripple the Confederacy's use of slaves in the civil war effort. Under the measure, if a seceded state chose to return to the Union before January 1, the state would not have to make slavery illegal. But, if the state refused to return, then enslaved people would be free.

"The Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people in the Confederacy. It did not deal with those who were enslaved in Union territory,” White said. “The figurehead is always the story of Gordon Granger bringing the story that the civil war is over and the Confederacy has lost. But, that doesn't mean white Texans wanted to give up the free labor. Free labor is what this country is built on and enslavers did not want to free the slaves. There were beatings, lynchings, and shootings as people tried to take their own freedom.”

The freedom promised to slaves in rebellious states through the proclamation depended on the Union military defeating the Confederacy. For the enslaved, it turned into a war for freedom. According to The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors served for the Union. Slaves fought to secure their own liberty. In the South, slaves also had to struggle for freedom through self-liberation or intervention from Union forces.

"You could only celebrate so much. They were de facto enslaved, and many stayed in bondage because of the threat of violence,” White said. "Initially, when we talk about the first Juneteenth celebrations in 1866, there's rejoicing. But, because of oppression, Jim Crow era, the rise of white supremacy on the back of Black freedom, you had a suppression of those exuberant expressions of joy of freedom. But, as you move into the civil rights era, you start to see a sense of Black pride and Black power emerging. Through that, you had this rebirth of the celebration of Juneteenth in the 20th and then subsequently in the 21st century today.”

Although Juneteenth has long been celebrated in the African American community, the monumental event remains largely unknown to most Americans. Juneteenth is now officially a federal holiday in the U.S. Congress passed legislation establishing the holiday on June 16, 2021. The following day, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law.

Juneteenth was originally recognized in Texas on June 19, 1866, before spreading to other neighboring states. Celebrations, typically, include prayer and religious services, speeches, educational events, family gatherings and picnics, and festivals with food, music, and dancing. The holiday also celebrates Black culture, history, and achievements, nationally and internationally.

Freedom Day The life and legacy of Peter Hunt

Denise Griggs is the author and publisher of a book titled "A Mulatto Slave: The events in the life of Peter Hunt, 1844-1915." The purpose of the book is to help educate readers nationwide, especially teenagers, about the life-threatening challenges Black families faced during the slavery-era in America.

In May 2021, during the annual Sons & Daughters of the United States Middle Passage Conference in Trenton, New Jersey, Griggs received the Phillis Wheatley Book Award for “A Mulatto Slave: The events in the life of Peter Hunt, 1844-1915.” She wrote the book "in the style of the Writer’s Federal Project (WPA) of the 1930s when African American former slaves were interviewed."

“It's almost like an autobiography,” said Griggs. “I didn't write the book with all my feelings and everything. I wrote the book as though Peter Hunt was talking after reading his pension files, answers to the different questions, and about his mother and their situation. I also made a timeline of all the other things that were happening around the world."

As a genealogist, Griggs has been helping Black people in the Greater Sacramento-region trace their roots to America's dark past. For years, she's also been researching her own bloodline. After questioning aging family members and digging deeper into the unknown, Griggs discovered she's the 3rd great-niece of Peter Hunt and 3rd great-granddaughter of America Hunt.

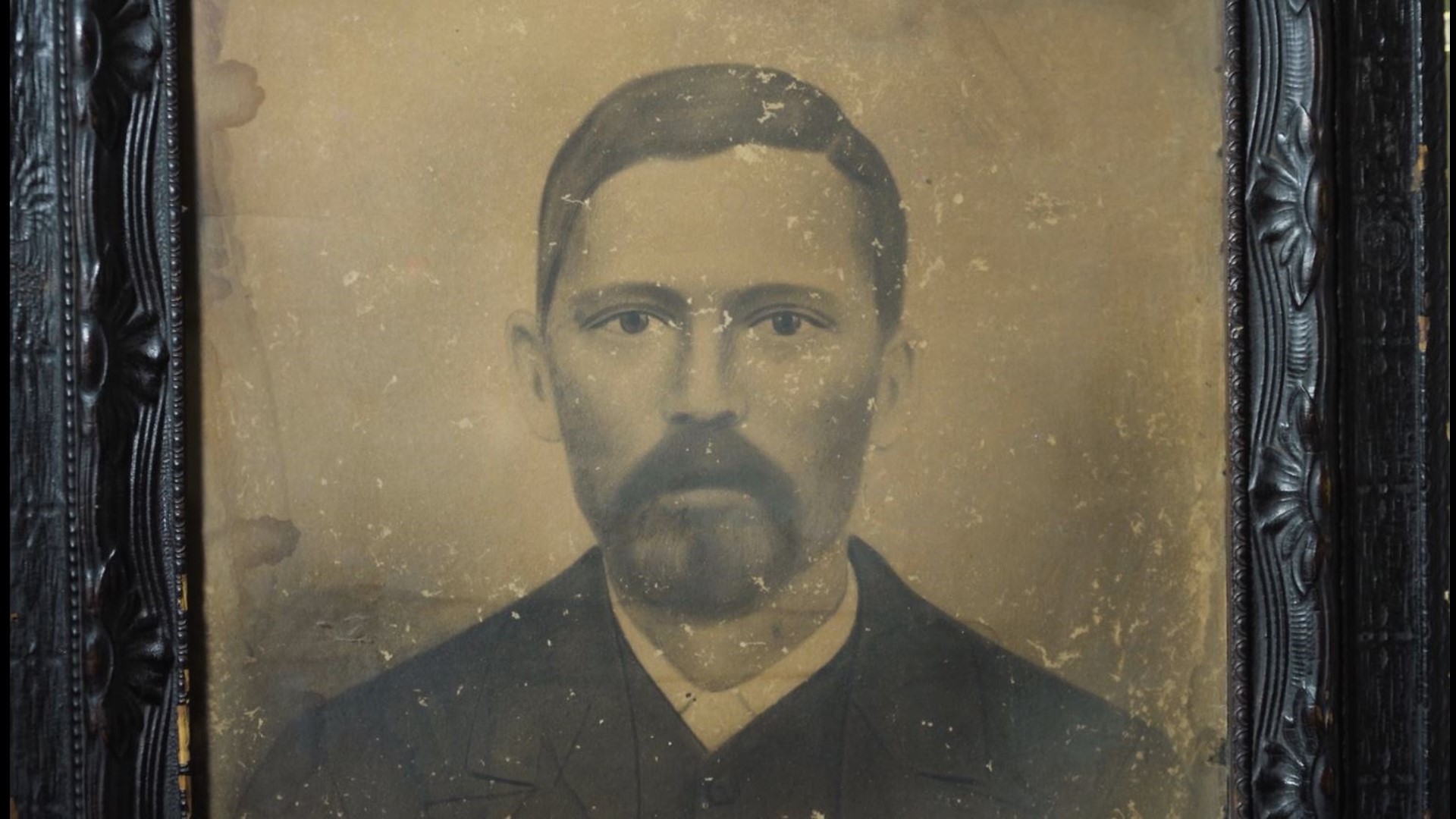

"When I first saw his picture, my aunt kept asking, 'what are you looking at?' I saw the picture on the wall, and I asked her, 'who is he?' And, she said, 'Oh, that's Peter," Griggs explained. "Ancestry and FamilySearch wasn't available. So, I went to a Mississippi website, and I put it out there that I'm looking for information on Peter Hunt."

Peter Hunt was born into slavery on August 5, 1844, in Liberty in Amite County, Mississippi. He's the son of America Hunt, a Black female slave, and Captain Henry Hunt, a white male slave owner. Historical documents describe Hunt the slave as “5'10, gray hair, gray eyes, complexion mulatto, and hard to distinguish from a white man.” He lived and worked on a plantation as a tanner.

“He was a tanner, tanning hides for hats, belts, saddles, and chaps,” Griggs said.

In 1856, the slaveowner moved his white family and Black slaves to Franklin County, Mississippi. Despite the deadly consequences, as a slave, Hunt learned how to read and write. Through the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, Hunt earned freedom at the age of 18. He enlisted in the Union Army's United States Colored Troops, along with thousands of other Black former slaves.

From 1864 to 1866, Hunt served in the Union Army as a garrison guard, working to defeat the Confederacy in the American civil war. He was promoted from a private to a sergeant. According to The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, about 179, 000 Black men served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and 19,000 served in the navy by the end of the war. Nearly 40,000 Black soldiers died over the course of the war.

“More men in the civil war died from disease as opposed to being shot and killed," said Griggs. "Peter came down with the measles. They expected him to die, too, but he didn't. By the time he filed for his pension, he names his wives, he names who he was in the service with, what happened to some of them, and those pension files are in NARA's Washington, D.C., the National Archives.”

In 1872, Hunt married Emily Shavers. The next year, the couple had one son named Albert Hunt. Through the Homestead Act of 1862, Hunt claimed more than 157 acres of land in 1874. The Homestead Act gave citizens or future citizens up to 160 acres of public land. The person had to live on the land, improve the land, and pay a registration fee. The government granted more than 270 million acres of land while the law was in effect.

“The Homestead Act of 1862, Lincoln signed that into law,” Griggs said. “It was to be enacted on January 1, 1863. It didn't say it couldn't be slaves. They were not to ask what nationality they were. It was also open to women. My 3rd great-grandmother, America Hunt, filed for a little over 39 acres in about 1883. She had anywhere from five to seven years to improve the land. She built a 16x16 foot square log cabin. She had corn cribs, where they kept the corn throughout the winter. She had seven cows, a horse, and a yearling. Its total value was $130 dollars. But, she farmed about 15 acres of that land and fenced it off. But, she also had help. When she filed the homestead, she listed the helpers and witnesses."

By 1881, Hunt successfully went from being a slave to building a home, cultivating 25 acres for farming, and building five structures. On June 7, 1915, he died at the age of 70 in Mississippi. In the spirit of freedom, Hunt is listed on The African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. to honor his service, sacrifice, and legacy.

“I think, looking into his eyes, I'd say, thank you,” Griggs said. “Nobody knew anything about him. His grandkids didn't know, his great-grandkids didn't know. I can let go of that picture now and send him back home to Mississippi.”

To learn more about the life and legacy of Peter Hunt or to purchase the book “A Mulatto Slave: The events in the life of Peter Hunt, 1844-1915," visit the Blue Eclipse Publishing website or Amazon.

We want to hear from you

We may share your response with our staff. We respect your privacy. Your email address and phone number will not be published and by providing it, you agree to let us contact you regarding your response.