“I’m trying to baby myself and (am) doing everything that I can to keep healthy,” she said this past week while at Excela Square at Norwin. “I feel there’s about a 90% chance I wouldn’t get (COVID), but if I get it, I don’t feel that I’ll get it as bad and I don’t feel that it will last as long.”

Baldridge, a North Huntingdon resident in her 70s, is among the 56% of people in the U.S. who are fully vaccinated against COVID. In Pennsylvania, she is among nearly 58% of the total population and nearly 69% of those 18 or older who are fully vaccinated, as tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

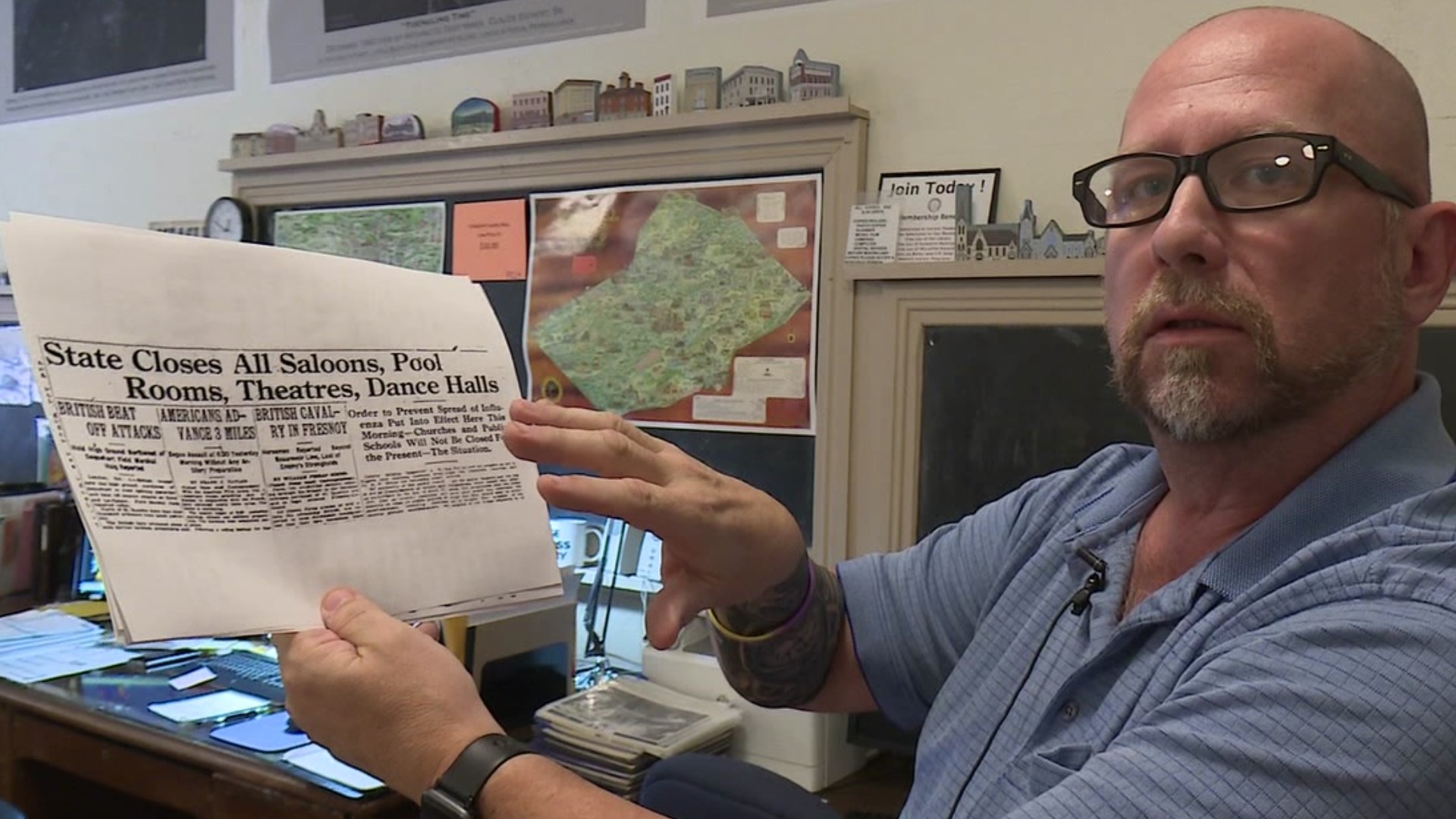

Vaccines have been hailed by the medical community as society’s quickest, safest path to emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. Their availability is arguably the biggest difference between today’s pandemic and the 1918 influenza pandemic.

That historical event, some medical experts say, can help frame the current one — and offer clues about where COVID-19 might lead.

‘Self-inflicted’

The United States recently surpassed the death toll from what became known as the Spanish flu pandemic — a mark unthinkable 18 months ago. On Friday, the U.S. eclipsed 700,000 deaths, and there have been about 4.8 million COVID deaths worldwide, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

The 1918 pandemic killed at least 675,000 lives nationwide and 50 million worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The United States, however, has tripled its population in the last century.

“We’re 100 years more advanced than we were then,” said Dr. Nate Shively, an infectious disease expert with Allegheny Health Network. “I think many would find that somewhat dispiriting, just that the pandemic continues to burn despite having really all the tools at our hands now to bring it close to an end. And we’re just not using all those tools effectively.”

Medical experts cite the vaccine as the most effective tool. The Pfizer booster shot recently was approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to extend protection for Americans who are older or have underlying medical conditions.

Yet many remain skeptical.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a Pittsburgh-based infectious disease expert and senior scholar at the John Hopkins Center for Health Security, called it “inexcusable” that the COVID-19 death total in the U.S. eclipsed that of the 1918 pandemic.

When people died of the flu in 1918, they didn’t have access to vaccines and today’s modern science. With the significant medical advancements made over the past 100 years, Adalja said, America should be handling this pandemic much better.

“What we’re doing in the United States is self-inflicted,” he said. “We can account for it by people not being receptive to science and openly defying it.”

‘Rates matter more’

Dr. Donald Burke, a distinguished professor — and former dean — at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, is an expert at using computer modeling and simulation to guide public health decision-making.

He said it’s important to consider the death rate and not simply the death total.

In Pennsylvania, COVID-19 has killed more than 29,000 people, according to the state Department of Health. The Keystone State was among the hardest hit in the 1918 pandemic, which claimed more than 60,000 lives here, according to the University of Pennsylvania.

The 1918 flu is believed to have caused about 4,500 deaths in Pittsburgh and another 2,000 in Westmoreland County. COVID-19 deaths so far have reached 2,100 in Allegheny County and 840 in Westmoreland.

“Even though the death totals are similar, the death rates — that is the rate per 100,000 people, or per-unit population — are lower now from COVID than it was for influenza by about three-fold,” Burke said. “Total numbers are important, but the rates matter more in understanding the impact.”

The 1918 flu pandemic largely impacted younger populations, with a “large proportion of the deaths” in individuals between the ages of 18 and 30. That was unusual for influenza and particularly straining for society, Burke said, as “the day-to-day functions of society are more dependent on that age group.”

Never went away

There is no straightforward definition for when a pandemic ends, said Seema Lakdawala, an associate professor who researches flu viruses in Pitt School of Medicine’s Department of Microbiology & Molecular Genetics.

The first U.S. cases of the 1918 pandemic were reported in March of that year, when more than 100 soldiers in Fort Riley, Kansas, became ill, according to the CDC. That was nearly a year after the United States entered World War I, with troop movements cited as a factor in spreading the disease.

Influenza remained rampant in Paris in early 1919, when the treaty to end the war was negotiated.

Lakdawala noted the H1N1 virus that was responsible for the 1918 pandemic never went away and continued to kill many people each year.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the virus was recognized as the cause. A vaccine to combat it was first recommended in 1960.

Even with vaccines, tens of thousands of Americans die each year from the flu, Lakdawala pointed out. In 2017-18, 80,000 people died from seasonal influenza, she said.

Still, Lakdawala, who also is a member of Pitt’s Center for Vaccine Research, said vaccines are the safest way to bring the spread of viruses under control — rather than trying to reach herd immunity through natural infection.

Beyond the risk of death, she said, “There are obviously long-term consequences of getting the virus. We’ve had it now for over a year, and we have long-term COVID symptoms,” including adverse effects on breathing and pulmonary function.

“As viruses replicate and spread through the population, they will evolve,” she said. “If we had a higher level of vaccination, we’d have less transmission and less diversity” in the COVID virus. “It’s not that it would go away, but it would definitely get slower.”

‘Pandemic is going to ease’

Burke said he anticipates that the COVID-19 pandemic will end much like the 1918 flu epidemic did — by morphing into a seasonal virus that never really leaves.

The 1918 flu “blew through the world’s population,” he said, infecting huge swaths, which gained natural immunity — the only answer at the time because vaccines were not yet a reality.

But COVID-19 vaccines are available and highly effective, Burke said. Once enough people have immunity — either from contracting the disease or from being inoculated — the pandemic will lessen, he said.

Even if vaccine uptake doesn’t improve, Adalja said, the pandemic will still taper down. But it will do so because people contract the virus and gain natural immunity rather than from being vaccinated. With infection, however, comes the risk of death, Adalja said.

“No matter what, the pandemic is going to ease because people get infected. Vaccines dampen the impact of the pandemic, but the final common pathway is going to be the same,” Adalja said.

That’s what happened with the 1918 flu, Burke said.

“It didn’t cause a major new pandemic again, but it caused seasonal flu, and it continues to mutate and evolve and cause significant disease — but never pandemic proportions,” Burke said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if COVID does pretty much the same thing. It’s unlikely to go away after a year or two because there are huge parts of the world that are not immune and are not vaccinated.

“As long as there are any populations on the planet that are susceptible, the virus will transmit.”

One positive outcome of the 1918 pandemic, though it was long in coming, was creation of the World Health Organization. Excela Latrobe pediatrics physician Dr. David Wyszomierski, who has studied the earlier pandemic, noted WHO in 1952 developed a global surveillance system to track different strains of influenza.

He said the COVID virus, like the flu, “can switch some of its genetic material to become more contagious or more pathologic.” That is what has occurred with the emergence of the delta variant, which has been cited in the recent increase in hospitalizations and deaths.

With another flu season approaching, Wyszomierski stressed the importance of getting a COVID-19 vaccine and an influenza vaccine for those who are eligible.

‘Absolutely not spared’

It may take over 90% of the population gaining some form of immunity before the pandemic tapers off, Shively said. Once it becomes controlled, it will likely become another of the “endemic coronaviruses.”

Four other coronaviruses circulate in the human population as common colds, Burke said. COVID-19 will likely join their ranks.

“If you look at the molecular evolutionary pattern, it looks like (coronaviruses) entered humans at least hundreds of years ago,” he said. “Maybe this happens every century or so, that a virus jumps and makes it into humans and then settles into this equilibrium.”

Still, there’s always a risk of another serious pandemic, experts warn.

“We are absolutely not spared from a new pandemic happening — be it 100 years in the future or later this year before this one is gone,” Shively said.

The risk of pandemics spreading is higher now than ever, Burke said. As the world becomes more interconnected, viruses have an easier time traveling globally — whereas many epidemics in the past died off on one continent or a lone corner of the world.

Several viruses in recent years, like Ebola and H1N1, had the potential to cause a devastating worldwide pandemic, Shively said. They just didn’t.

“Preparation for the next pandemic and learning lessons from this one is something that we as a country and an international community can gain,” he said. “When another pandemic will happen is hard to say, but another pandemic will happen. We need to take steps to make sure that we’re prepared for when it does.”