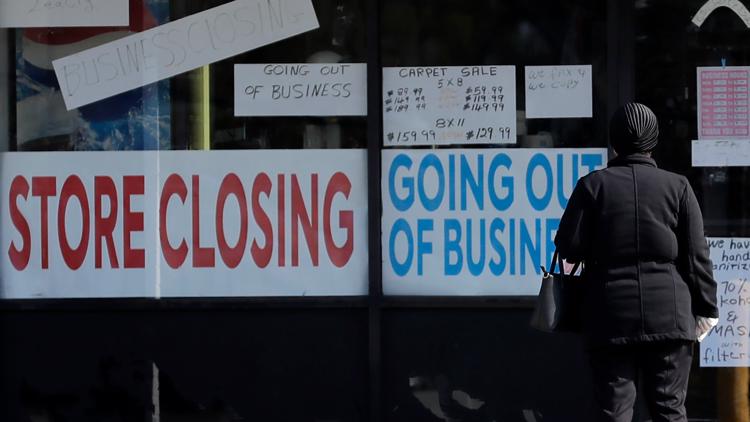

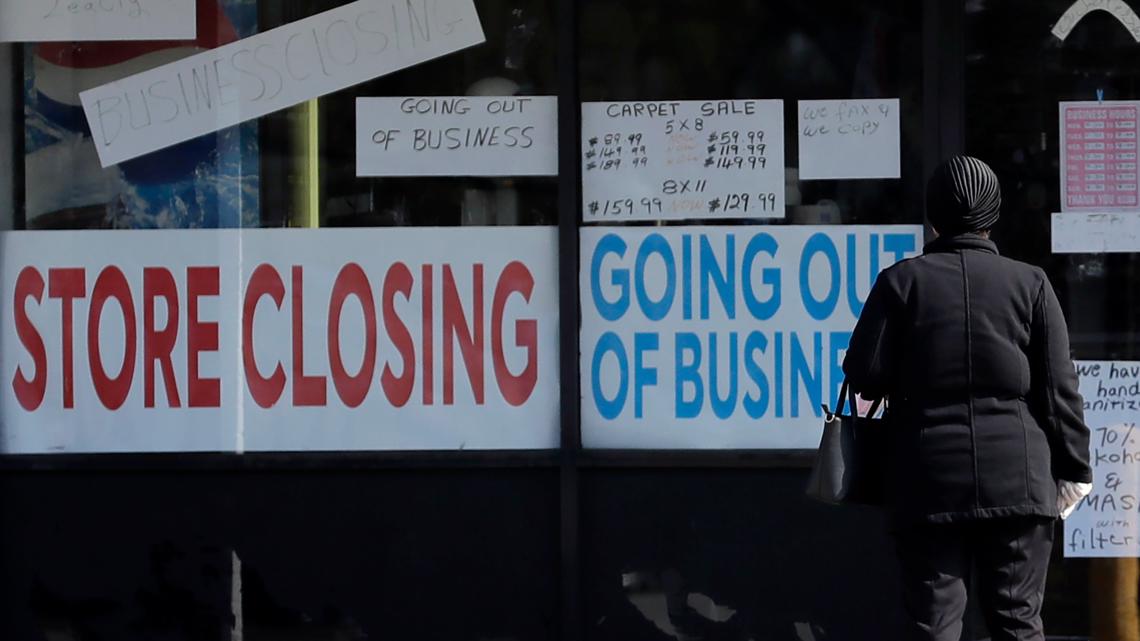

WASHINGTON — More than 2.4 million people applied for U.S. unemployment benefits last week in the latest wave of layoffs from the viral outbreak that triggered widespread business shutdowns two months ago and sent the economy into a deep recession.

Roughly 38.6 million people have now filed for jobless aid since the coronavirus forced millions of businesses to close their doors and shrink their workforces, the Labor Department said Thursday.

The number of weekly applications has slowed for seven straight weeks, and last week the figures declined in 38 states and the District of Columbia. Yet historically, they remain immense — roughly 10 times the typical figure that prevailed before the virus struck.

“While the steady decline in claims is good news, the labor market is still in terrible shape,” said Gus Faucher, chief economist at PNC Financial.

The continuing stream of heavy job cuts reflects an economy that is sinking into the worst recession since the Great Depression. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated this week that the economy is shrinking at a 38% annual rate in the April-June quarter. That would be by far the sharpest quarterly contraction on record.

Nearly half of Americans say that either their incomes have declined or they live with another adult who has lost pay through a job loss or reduced hours, the Census Bureau said in survey data released Wednesday More than one-fifth of Americans said they had little or no confidence in their ability to pay the next month’s rent or mortgage on time, the survey found.

During April, U.S. employers shed 20 million jobs, eliminating a decade’s worth of job growth in a single month. The unemployment rate reached 14.7%, the highest since the Depression. Millions of other people who were out of work weren’t counted as unemployed because they didn’t look for a new job.

Since then, 10 million more laid-off workers have applied for jobless benefits. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said in an interview Sunday that the unemployment rate could peak in May or June at 20% to 25%.

Across industries, major employers continue to announce job cuts. Uber said this week that it will lay off 3,000 employees, on top of 3,700 it has already cut, because demand for its ride-hailing services has plummeted. Vice, a TV and digital news organization tailored for younger people, announced 155 layoffs globally last week.

Digital publishers Quartz and BuzzFeed, magazine giant Conde Nast and the company that owns the business-focused The Economist magazine also announced job cuts last week.

The continuing job cuts reflect an economy that is gripped by the worst downturn since the Great Depression. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy is shrinking at a 38% annual rate in the April-June quarter. That would be, by far, the worst quarterly contraction on record.

The total number of people receiving benefits rose 2.5 million to 25 million in the week that ended May 9, the latest period for which data is available.

Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont, said the most recent layoffs may be particularly worrisome because they’re happening even as states are gradually reopening their economies. This could mean that many companies foresee scant likelihood of a substantial economic recovery anytime soon and so still feel a need to cut jobs.

“There’s a high probability that those layoffs could persist for longer than those that were a function of (businesses) just being closed,” Stanley said.

At the same time, some companies have begun to rehire a limited number of their laid-off employees as states have eased restrictions on movement and commerce.

One rehired worker, Norman Boughman, received an email last week from his boss at a second-hand clothing store in Richmond where he’d worked part time, asking him to return, one day before Virginia allowed most retailers to reopen.

Boughman, who had applied for unemployment benefits to no avail, was happy to be paid again. So far, the job seems secure to him, because the store has been busy, and the owner hasn’t expressed any concerns about business. But even while wearing a mask, Boughman worries about the potential threat to his health.

“We’re having to sort through people’s things, and I feel like that puts us at a higher risk,” he said.

Some economists see tentative signs that economic activity might be starting to recover, if only slightly, now that all the states have moved toward relaxing some restrictions on movement and commerce.

Last week, the three major U.S. automakers, plus Toyota and Honda, recalled roughly 130,000 of their employees back to factories for the first time since the plants had closed in March. That’s about half the industry’s workforce. Some auto executives say sales have held up well enough to support the recall of those employees.

Still, the automakers, like other businesses, are also grappling with the health risks of operating during a pandemic. On Tuesday, Ford had to halt production at two assembly plants after three workers tested positive for the coronavirus. The workers were quarantined for 14 days, and the plants underwent cleaning.

Data from Apple’s mapping service shows that more Americans are driving and searching for directions. Restaurant reservations have risen modestly in states that have been open longer, according to the app OpenTable, although they remain far below pre-virus levels.

In most industries, employees are working more hours than in mid-April, the peak of the virus-related shutdowns nationwide. Data from Kronos, a workforce management software company that tracks 3 million hourly workers, shows that shifts worked at its 30,000 client companies are up 16% since the week that ended April 12. The shifts are still down a sizable 25% from pre-virus levels.

Even in states that have been reopened the longest, like Georgia, not enough shoppers are visiting stores and restaurants to support significant rehiring, said David Gilbertson, an executive at Kronos.

“Our data is suggesting this recovery is going to take a while,” Gilbertson said.