CALIFORNIA, USA — Four years before George Floyd died at the hands of police, a man in Sacramento County died under similar circumstances. His name was Daniel Landeros.

“I first met him in third grade,” Jennifer Landeros, Daniel’s wife, said.

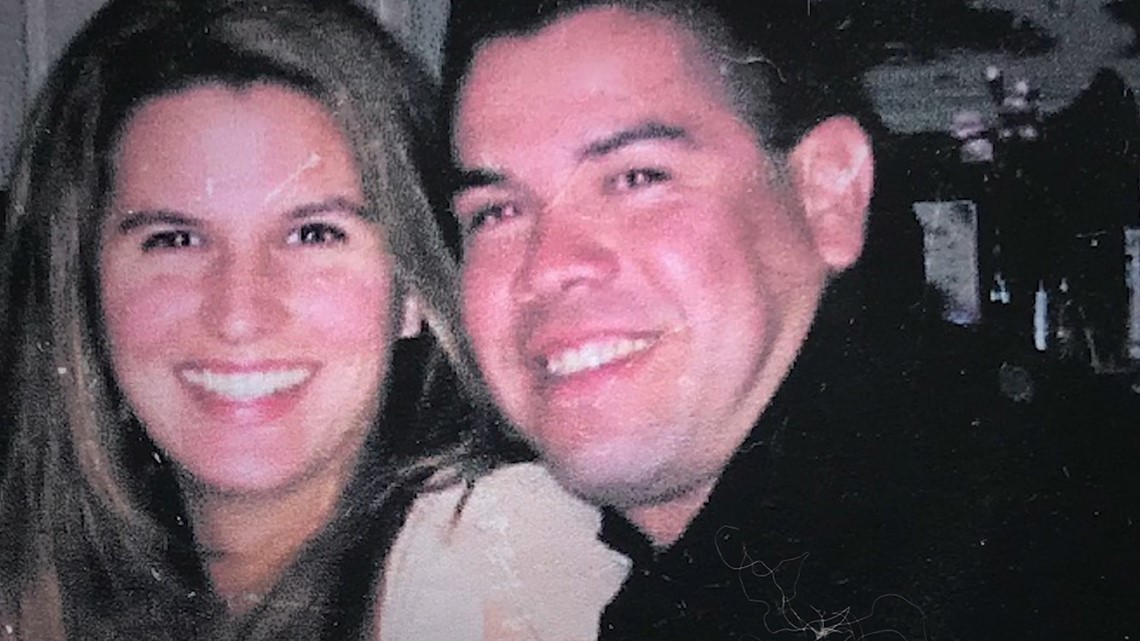

By high school, Jennifer and Daniel were inseparable. Hanging around their home, Jennifer has photos of them attending the winter formal and other high school dances together. She cherishes the photographs, saying she knew then that she was going to marry him.

Her vision came true. After growing up in Gilroy and marrying in Reno, Daniel convinced them to move to Elk Grove to raise their family. When he wasn’t busy working in the tile business, Jennifer remembers he would take their kids to the park or the 7-11 to get Slurpees.

“My husband was fun. He was the fun one. I was the more serious one so… they have good memories with him,” Jennifer said. “And they talk about it. We always talk about him.”

NOVEMBER 30, 2016

Nearly a week after Thanksgiving, Jennifer and Daniel decided to make a quick evening trip to the store.

“He wasn’t really acting like himself,” Jennifer said. “I don’t know, he was just a little off.”

Jennifer said Daniel’s driving was worrisome. She had no idea he had methamphetamines in his system.

Thinking of her kids awaiting their return at home, she decided to have Daniel pull over and she got out of the car. Once she hopped out, he drove on and she had their eldest daughter come and pick her up.

Out of concern for his and others' safety, she decided to ask for help and called the Elk Grove Police’s non-emergency line.

“Never thinking not for one second anything like this would happen,” Jennifer said.

After Jennifer got out, Daniel got into a car accident and tried to run from police when they arrived on scene. The two Elk Grove Police officers pursuing Daniel used a taser, then handcuffed him. When he continued to resist, officers used their body weight on top of his back as he laid face down. They also called over more officers.

“Four police officers at one time were on him. I think they said it was like 800 pounds on top of him… at one time,” Jennifer said. “I don’t know why they had to do that when he was face down on the ground with his hands handcuffed behind his back. I don’t know why they felt they had to stay on him, especially if he wasn’t moving.”

Audio from body camera footage showed police continue to hold Daniel down while waiting for a wrap, a device that allows a person to be restrained but out of prone position. During these minutes, body camera footage shows Daniel ceasing to resist the officers and growing silent.

As an officer carried in the wrap and they figured out a plan to use it, one officer noticed Daniel was blue and bleeding heavily from his nose.

“Hey! Hey! Get him off his nose, dude. He’s turning blue,” the officer said.

Officers turned Daniel over and began administering CPR.

“He’s not responsive. Dude, he’s blue,” body camera footage captured officers saying.

He was transported to the hospital where he was pronounced dead, leaving behind his wife and five children.

“It sucks… they don’t have a dad,” Jennifer said. “He was a really good guy and a good dad. He took care of us, you know?”

In the Sacramento County District Attorney’s investigation, an autopsy concluded that Daniel’s sudden death was due to restraint as well as methamphetamine intoxication.

POSITIONAL ASPHYXIA: AN UNACKNOWLEDGED PROBLEM

Daniel’s death occurred in Sacramento County in 2016. Yet, most of the world wasn’t familiar with the dangers of a person being under the weight of officers while in a prone position until May 25, 2020, the day George Floyd died, sparking an eruption of massive outcry and protests nationwide.

In response to the practice, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered police training programs in the state to stop teaching officers how to use the carotid hold.

“[The carotid hold] is literally designed to stop people’s blood from flowing into their brain,” Newsom in a press conference said. “That has no place any longer. It’s the 21st century.”

But the carotid hold is different than the prone position.

The prone is a position where the individual is lying flat, chest down, and back up. The carotid hold is a restraint that specifically reduces blood flow to the brain. George Floyd was in a prone position and the officer used a carotid hold with his knee.

RELATED: PRONE: Facedown and handcuffed is no way to die, yet it keeps happening over and over again

But the prone position alone can be deadly, especially when officers' weight is applied because it can cause positional asphyxia.

“[If a healthy] individual was placed in [the prone] position with nothing else going on, it’d be very rare that’d result in death,” Izaak Schwaiger, an attorney that specializes in police misconduct, said. “But for individuals who’ve been in a scuffle with police… if you’re under the influence of some kind of stimulant like cocaine or methamphetamine -- which is often the case in these kind of things – that often brings certain risks into play. If you’re obese, that brings extra risk factors into play. So, when you combine all these [and] you put that person face down… bad things are going to happen [and when] you add weight to their back, as we saw in many of these recent cases, George Floyd included, then the problem just accelerates.”

ABC10 was part of a nationwide investigation that looked at over 100 deaths caused by positional asphyxia within the last 10 years, highlighting the national problem. Data collected from the California Department of Justice shows the same is true in California. In 2019 alone, there were around 280 use-of-force incidents by police that resulted in serious bodily injury or deaths that involved the carotid hold or another type of control hold.

So if we’ve outlawed, specifically, the carotid hold in California, what’s our law enforcement’s stance on other control holds that could cause positional asphyxia, like putting a person handcuffed in the prone position? And then applying weight in that position?

That’s where it varies.

“Policies between agencies are going to be different,” Schwaiger said. “You can have two cities that are five miles apart from each other that have very different policies.”

As for the Elk Grove Police Department’s policy on prone position, well, they don’t have one.

This was revealed when Jennifer went looking for answers about her husband’s death. She said Elk Grove police didn’t give her any specifics, leading her to believe Daniel was killed in the car accident, not after.

“I wanted to know what happened to my husband,” Jennifer said. “Because they didn’t say like, ‘Oh we arrested him,’ or ‘He died in custody.’ None of that.”

She decided to sue, which she said helped give her insight, around a year after his death, into what actually happened that night.

The lawsuit led to a deposition where Jennifer’s attorney, Stewart Katz, demanded answers from the Elk Grove Police Department on their protocol for prone position. Katz questioned Bruce Praet, who represented the Elk Grove Police Department. The certified deposition reads:

Q: [In reference to the Elk Grove Police Department Policy Manual] Did the policy address whether or not there were any potential risks about keeping handcuffed individuals in a prone position?

A: No. Not specifically to prone.

Q: Okay. Did the policy address any risks concerned to having weight placed upon handcuffed individuals?

A: No.

We followed up with the Elk Grove Police Department to see if they’ve updated their policy to include prone position or positional asphyxia in the years following Daniel’s death in 2016. They said while prone position isn’t in their policy, they train arrest control techniques that address the best practices of safely detaining someone using the prone position.

Just hours away in Rohnert Park, Calif., Schwaiger said officers weren’t even trained on positional asphyxia prior to the death of Branch Wroth in 2017. He died after being held down under police’s weight in a prone position. Schwaiger represented his family in a lawsuit against the city following his death.

“The city of Rohnert Park, it wasn’t in their policy manual per se, but they specifically trained their officers that there’s no such thing as positional asphyxia,” Schwaiger said. “I mean… that’s dangerous.”

The Wroth family sued the city of Rohnert Park, which went to trial and the jury awarded a $4 million verdict, which was later reversed by U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar who ordered a new trial after finding legal errors in written instructions given by the trial judge to the jury. Schwaiger said due to COVID and the anticipated appeals that would follow a second verdict, they decided to settle for $2 million.

But these two agencies aren’t alone, not a lot of law enforcement agencies have policies specified to restraining someone in a prone position.

“There won’t be [an overall policy that says you can’t apply weight to someone’s back in a prone position]. The wording of all these policies will say that the officers may use force which is objectively reasonable,” Schwaiger said.

WHAT IT'S COSTING YOU

So, when deaths occur because of positional asphyxia from prone restraints, if it’s the city or police that are being sued, who’s footing the bill?

“Ultimately, just like if you or I were in an automobile accident and hurt someone, we have insurance to cover it. We have to pay a deductible and the insurance kicks in the rest up to a certain amount,” said Schwaiger. “Municipalities in California are the same. That is they have to pay their deductible, their out of pocket, and then the insurance provider kicks in the rest.”

But that could kick up the overall cost of a city’s insurance premium.

“Even though the taxpayer is not paying these verdicts or settlements directly, it is coming out of their pockets in the end because they have to pay next year’s increased premiums, which are substantial,” Schwaiger said.

It’s impacted places like Vallejo and Sonoma in the past.

“[In Sonoma County] there have been so many police-related deaths that the county sheriff’s insurance has tripled or come close to tripling,” said Schwaiger. “I think the city of Vallejo was considering bankruptcy because of all the payouts they were having. But that was a long time ago.”

So, what’s happening locally?

The city of Sacramento said in its 2019 risk management annual report that police liability is one of the most expensive claims – and this isn’t including attorney fees which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

From 2018 to 2019, total insurance premiums increased by 22% in the city of Sacramento. From $4,636,970 to $5,662,420, a $1,025,450 increase.

The city of Elk Grove said their total insurance premiums only increased just over $62,000, from $519,183 to $581,985, which they credit to the general cost of insurance and not police lawsuits. However, the Landeros’ case has yet to be heard in front of a jury or settle. Jennifer said that in suing, she hopes to prevent this use of force in the future.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen but it’s discouraging, actually, because it just keeps happening over and over and over again,” Jennifer said.

We reached out to the Elk Grove Police Department requesting an interview for this story. They said due to pending litigation, they could not grant an interview or comment.