SACRAMENTO, Calif. — “There wasn’t proper testing. They just went by basic symptoms,” Sacramento City Historian Marcia Eymann said. “People were definitely paranoid – ‘Is it safe to go out? Can we do this? Is it in our food?’”

Sound familiar?

Shockingly, Eymann isn’t referring to our current coronavirus pandemic, but rather the Spanish flu.

“We’ve seen different epidemics, but really there’s only been one other,” Eymann said. “The last time that we had a pandemic reach this scale was in 1918.”

SIMILARITIES

Much like the coronavirus is doing now in the spring of 2020, the Spanish flu completely overtook society over one hundred years ago. Despite 102 years passing since then, the similarities are eerie.

According to Eymann, they understood it was a “crowd disease” or that it spread when large groups of people gathered together. The contagiousness of it being passed through nose, eyes, coughing and sneezing were also of concern.

That’s why, just like today, movie theaters, churches and places of public gathering were closed. Ironically, Eymann said saloons in Sacramento remained open. While bars today were one of the first businesses ordered to shut down, alcohol laws have changed so restaurants can sell to-go alcohol.

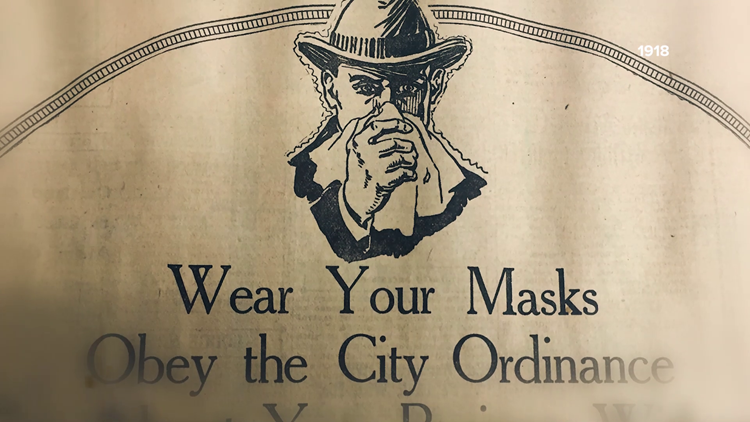

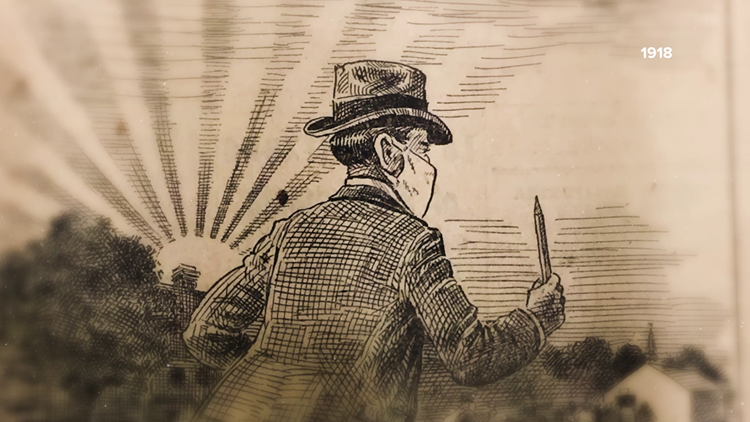

Residents of Sacramento and other cities were also required to wear a mask.

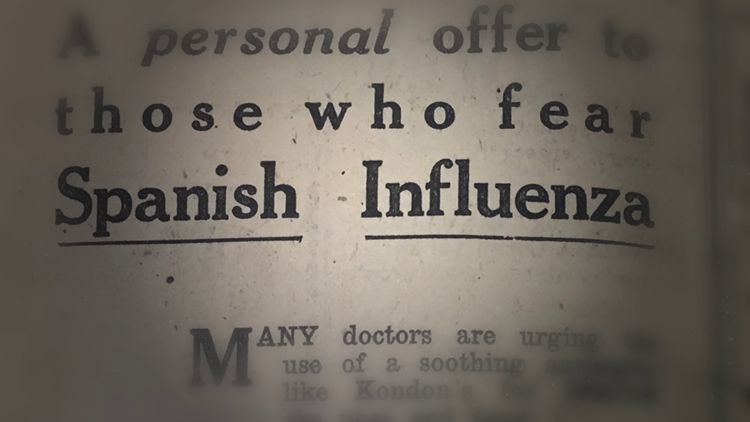

Photos: Spanish flu in the news

“There wasn’t proper testing to say, ‘Oh yeah, you have the Spanish flu,’” Eymann said. “They just went by basic symptoms.”

While our medical advances have allowed for us to be able to create COVID-19 tests, the distribution of them has been an issue, causing a like-minded approach to the Spanish flu in terms of officials telling those with symptoms to stay home and self quarantine.

Another similarity is the terms for both viruses. President Trump has often referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” something which has been a topic of controversy and concern regarding racism towards Asian Americans amidst the pandemic. President Trump has said he referred to it as the Chinese virus as it came from China. The Spanish flu got its name from another country as well, obviously, Spain.

“[The Spanish flu] didn’t originate in Spain, but Spain had the highest amount of cases, so it just took on the name,” said Eymann.

The perils of the Spanish flu pandemic occurred during an election year, just like how the coronavirus is taking place during an election year.

WHAT HAPPENED

The first case of Spanish flu came to California in September 1918, Eymann said. Part of the spread was due in part to large gatherings at World War I parades.

“They said you’d be a ‘slacker’ if you didn’t turn out for this event,” Eymann said. “We know that 1,500 people were in the parade and over 3,000 people came and lined the streets to participate. Directly after that we see a rise in illness.”

The Spanish flu was incredibly deadly worldwide.

“Somewhere between 40 million to 100 million people died globally and in the United States there was about 675,000 deaths, which is more deaths not only in World War I, but in the 20th century wars for the United States,” UC Berkeley Historian Professor Ronit Stahl said.

As both COVID-19 and the Spanish flu spread by contact, more urban and populated areas like New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles were and have been most impacted.

But in the 102 years that have passed, communication has changed. Today we’re able to Zoom, FaceTime, call, text, email and use the internet and television to stay updated. In 1918, they relied on the newspaper. Eymann said this was an issue, especially for poor people, who didn’t have access to the newspaper. That’s why, like today, we’re all encouraged to stay connected.

“The similarity is know your neighbors, check on them, check on your friends,” Eymann said.

The sentiment of connection and caring is one that conveys how people will always step up, no matter what year it is. Dancers at an “art house” in Sacramento, Eymann assumes “took off layers of their clothing,” stepped up in a big way. Out of work, they volunteered to go into homes to take care of others.

According to historians, the handling of the Spanish flu was done mostly by women as World War I was taking place and many male soldiers were abroad. It also created change.

“One of the biggest shifts that occurred in the midst of the 1918 pandemic in the military was actually allowing African American women to serve as nurses,” Stahl said. “They had been prohibited before and there was a massive personnel need.”

While it was good news and work for this particular group, many were out of jobs, something many can relate to today. So many, in fact, that economic-wise, we are in a place closer to the Great Depression, rather than the Spanish flu pandemic.

“In terms of unemployment [between the Great Depression and COVID-19 pandemic], the numbers are spot on,” Sacramento State Professor and Economist Dr. Kace Chalmers said. “I would not be surprised to see unemployment rates be north of 20-percent easily in the next month or so.”

Like those who survived through the Great Depression, Chalmers believed our pandemic will impact this generation’s habits in terms of spending, saving and even keeping extra food on hand.

On the other hand, while the most vulnerable to COVID-19 are the elderly and those with previous health conditions, the Spanish flu wreaked havoc on younger individuals, many of whom were in the working class. Chalmers believes this difference will help our economy as the labor supply “won’t be as affected as it could be.”

NOT HER FIRST QUARANTINE

For many of us, this pandemic is an unprecedented time. Our quiet world of social distancing and sheltering in place is a new and odd normal. But it’s not for all.

“I had to quarantine when I was nine years old,” Betts Riolo recalled.

Riolo is now 88 and resides in a senior living community in Vermont. But she grew up in Sacramento and remembers when a scarlet fever outbreak caused her family to quarantine.

As her father stayed with friends in order to continue “making a living,” Betts stayed home with her brother and mother. She remembers her mother being very ill, but when she recovered… it was a time of joy.

“Dad would step on the front porch and I remember on Valentine’s Day, he brought my mom a little rocking chair and sat it on the porch as a gift,” Riolo said. “We would just wave and throw him kisses.”

“It was a time I remember as a very, very special time because my mom always worked and we had her alone for three weeks. When she was feeling better, she would play games with us and we would have a tea party every afternoon,” Riolo said. “So for today’s parents who are having this problem at home, their kids may be enjoying it more than they think they are.”

Riolo also remembers her school sending her book to stay up to date on her schoolwork. To avoid infections in other students, the school allowed her to destroy the books, in case the books picked up any germs. When she did return to school, she said the school took each student’s temperature before they entered the facility. It’s a type of protocol we’re still using today.

“Scarlet fever was actually very important for these kinds of measures we’re seeing in the present day with COVID-19,” John Hopkins Medical Historian Dr. Graham Mooney said.

Mooney added the biggest change from past pandemics we can now see is the use of antibiotics and vaccines. But another similarity we’re seeing is the aspect of isolation, and visitation within that lonely world.

“Scarlet fever was one of the diseases that isolation hospitals were set up to manage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” Mooney said. “[Infected patients] could only be visited through what they called ‘window appointments.’”

But treatments aren’t the only aspect that carry on from past pandemics. There’s a likeness of disease impacting minority groups. According to multiple professionals, minority, immigrant and overall poor communities had a lesser ability of accessing healthcare both during the Spanish flu and currently during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This pandemic seems to be exposing the cracks in our public healthcare system that have always sort of been there, but have been easy to glass over or ignore,” Chalmers said. “When you look at the infection within the African American or Hispanic populations and how much higher they are, part of it is because they’re in jobs that are considered essential and part of it is because they deal with more stress and are less likely to have access to healthcare.”

WHAT CAN WE LEARN?

Despite so many parallels, the devastation of past pandemics has been all but forgotten.

Stahl believes that was in part because there was no individual or vaccine that “cured” and ended the pandemic. There’s no one to attribute the ending to. Historians believe herd immunity was eventually developed. But not before multiple waves.

“One of the things about the 1918 Spanish flu is that it actually came in three waves and the second wave was the most lethal,” Chalmers said. “The first wave came through and abated and everyone thought, 'phew it’s over,' and then it popped back up again because we sort of returned to normal too quickly.’

In Sacramento, Eymann said when cases started going down, they relaxed rules like enforcing masks. However, as cases rose during the second wave, Eymann said Sacramento reinforced their mask policy.

After the waves, society opened back up, but things didn’t go right back to normal.

“The [Sacramento] Bee had a basketball league and they said the basketball league could go on because it helped the morale of the community. People in the audience had to wear masks, but the players didn’t. The minute they stepped off the court, they had to put a mask on. Same thing with baseball players,” Eymann said.

The need to document cases helped implement new protocol locally. Eymann said Sacramento was the first city in the United States to begin documenting and tracking diseases in the area. The Spanish flu also impacted the political landscape for years to come. Warren Harding’s slogan during his presidential race was “A Return to Normalcy.”

“I think we can learn from the 1920 election that the desire for what people perceive as normalcy absolutely can affect choices in the voting booth and I think has at least influenced some of the current takes on, if not the 2020 election yet, then the democratic primary,” Stahl said.

Philosopher and poet George Santayana’s quote poses an interesting question: Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it. So what’s the biggest lesson from, in particular, the Spanish flu, which is the most similar to the pandemic we’re currently in.

“History in so many ways is about cycles and patterns, but it’s also about understanding change over time, context and contingencies. I think that last part – contingencies – is really important in drawing comparisons to the past, but also in being careful about how we draw those comparisons because 2020 is not the same as 1920,” Stahl said. “I think one of the big lessons from that is that transparency does matter.”

Other historians have had similar sentiments regarding transparency.

“It’s why you need transparency and it’s why politicians need to be able to be, the ones who are making the decisions on our behalf about where resources go and when it’s going to be okay to go back to school and go back to work,” Mooney said. “It’s why they need to be open to scrutiny as much as possible.”

As for our own roaring twenties, Stahl believes by looking back, it may show us what’s in store when this pandemic ends.

“It seemed as the U.S. moved into the 1920s, the jazz age was in certain ways an era of fun and play and forgetting of both influenza and war and so I think that perhaps tells us something psychologically about how we operate,” Stahl said.

For now, despite these trying times, we can look back as a means of faith that we will get through this – even with our current uncertainty of our recovery.