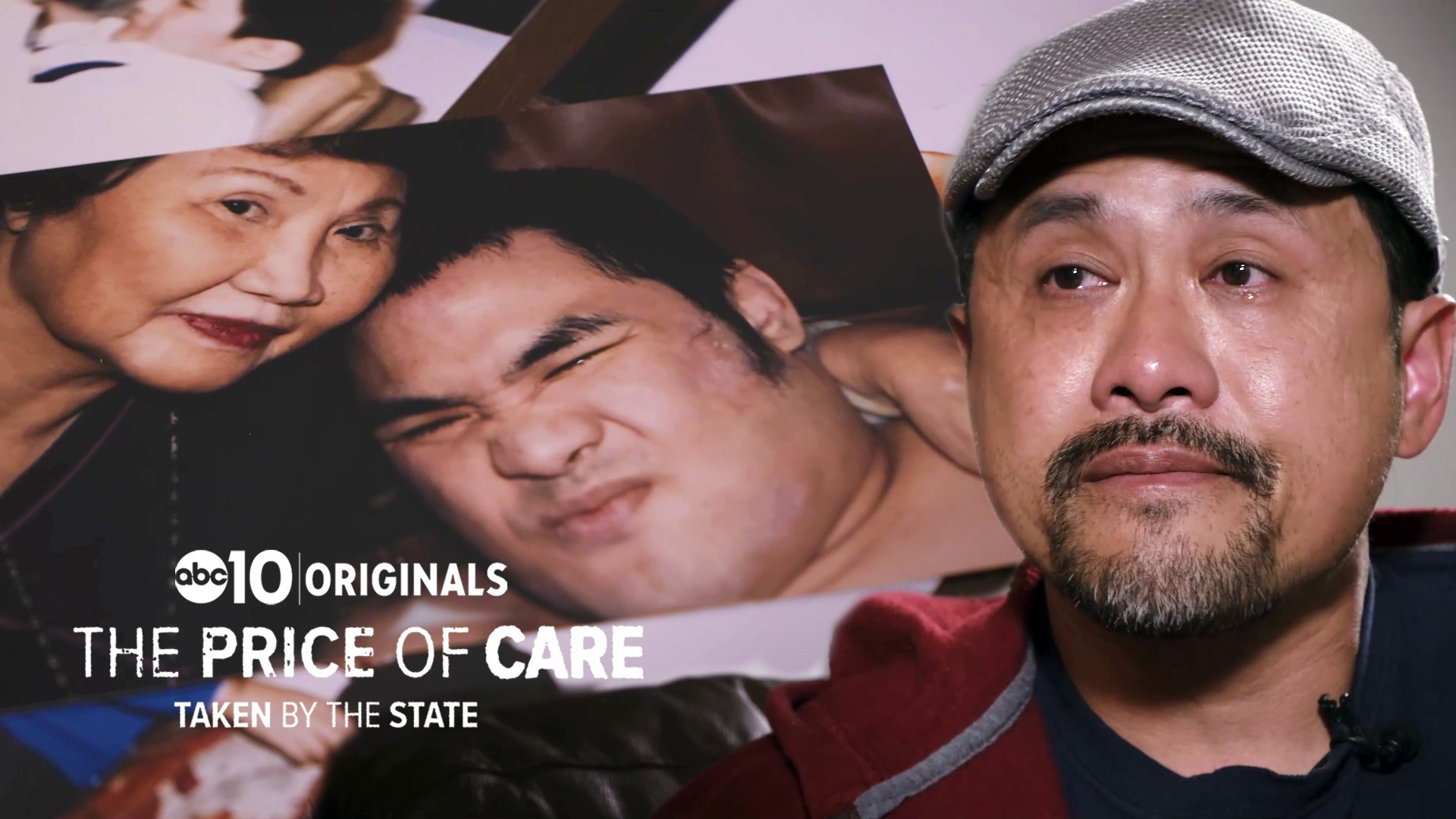

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — “The family was talking about, ‘Why not move to California?’” said James Bui.

In Aug. 2013, the Bui family packed up their lives and headed west. It wasn’t a move for sprawling beaches or eternal sunshine, but for a better future for a loved one.

“California policy and law around disabilities… it sounds wonderful, right?!” said James. “It sounds game-changing in many ways.”

Our rights for those with disabilities paired with California’s vast Vietnamese population made it seem like the perfect destination for their family.

“[The] largest community outside of Vietnam,” said James.

Disability laws in California are unlike any other state. It’s what appealed to the Bui family for the youngest out of their 11 siblings -- Martin.

“Martin was born in 1980,” said James. “He was born with a traumatic brain injury and was later diagnosed with autism.”

His condition stemmed from medical malpractice.

“He was born, he was bleeding. I think even the nurse was on record saying, ‘This is not normal,’” said James.

He never developed skills to speak, read, write or sit still, court records show. In Illinois and Florida, the states the Bui’s lived in prior to California, Martin’s parents were appointed as his guardians – what’s known as conservators in California.

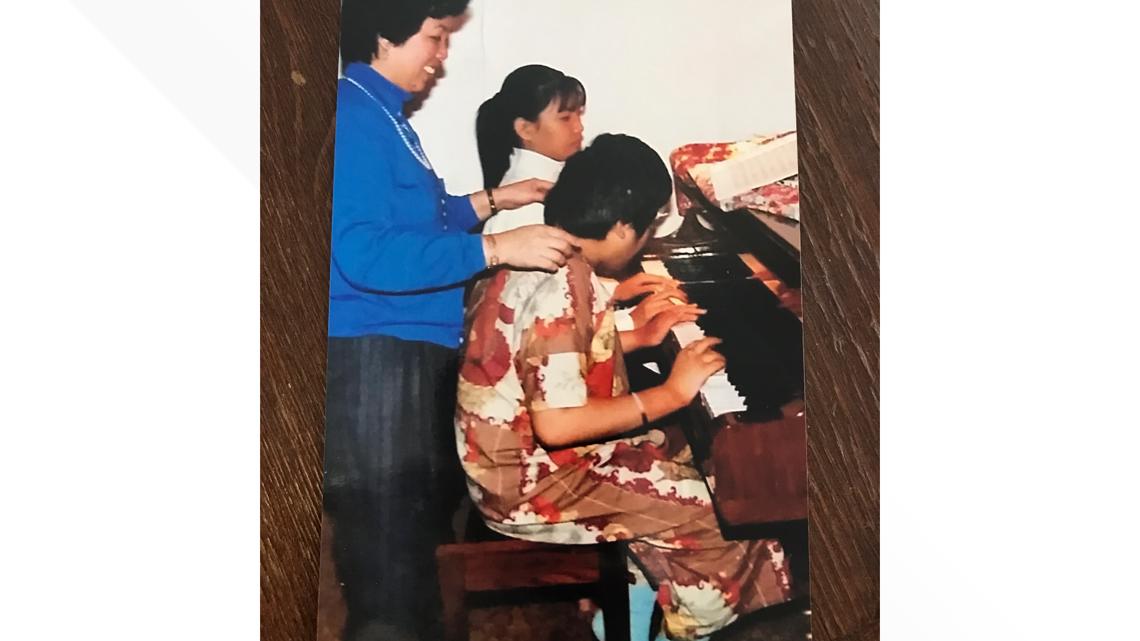

“My mom was his everything,” said James. “My mom cherished him.”

While Martin and his mother had a beloved bond, each sibling formed their own unique connection. For James and Martin, it was through music.

“As he listened, you’d watch him rock his head. He’d beatbox to certain kinds of percussions,” said James. “It was our way of spending time, acknowledging that he’s communicating.”

In return, Martin taught him.

“I just think disabilities is a misnomer in terms of a word. People have gifts and maybe at the time – being younger – you’re conditioned to think it’s a problem,” said James. “But looking back in retrospect, the kind of learning I’ve gained as a person just growing up with him, I received a lot. It made me who I am – as a father, as a sibling, as someone who cares.”

James and his family care deeply about Martin. They thought the state of California would too.

California’s system ensures people with disabilities like Martin have equal rights through the Lanterman Act, which was passed in 1969. Under this law, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) was created.

The taxpayer-funded department oversees regional centers throughout the state. The centers provide services to people with disabilities as well as their families.

DDS has an important responsibility: the well-being and equality of Californians with disabilities.

But DDS is not doing their job, according to a state audit.

“They’re not really doing a good job of really overseeing these regional centers and ensuring they’re overseeing the vendors,” said Michael Tilden, the acting California State Auditor.

The June 2022 report’s title sums up the findings: “The Department of Developmental Services: It Has Not Ensured That Regional Centers Have the Necessary Resources to Effectively Service Californians With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.”

The California State Auditor found DDS lacked oversight in several critical areas, like ensuring people have convenient access to services – seemingly the entire point of DDS.

“It’s about the timeliness of receiving the services and the convenience of access,” said Tilden. “And the real issue here is we couldn’t really evaluate that because basically DDS and regional centers are not tracking that data.”

Anyone unable to get regional center services should be able to file a complaint.

In reviewing three regional centers, the auditors found DDS isn’t making sure clients know they can file complaints – or how to – and if a complaint is actually filed, investigations into those complaints are not being completed in a timely manner, the audit showed.

“On average we found the three regional centers (examined for the audit) exceeded the 20-day (required) timeframe, 60% of the time,” said Laura Kearney, California Audit Principal.

DDS also failed to review the live-in care facilities they fund, which they call “vendors,” to make sure they were safe for clients even though quality reviews are required by state law and in the few reviews done, what’s been found is alarming.

“There were errors with dispensing medication,” said Tilden. “There was a lack of documentation for instructions on how to provide medication to consumers. There were also some safety issues around mold in different facilities.”

Our investigation found these facilities are where 86% of people conserved by DDS live, including Andrew Findley – Deborah’s son who we introduced you to in episode two of this investigation.

According to a July 2022 facility evaluation report by the California Department of Social Services, staff failed on multiple occasions to correctly administer prescription medication.

We asked the Department of Developmental Services repeatedly for an on-camera interview for eight months. When they declined, we sent them a detailed list of questions like, “Why, without checking these facilities, DDS believes they’re better for those under their conservatorship to live rather than at home?”

DDS refused to give us an on-camera interview but sent us a written response and a video of their Director Nancy Bargmann reading that response. Both are included below, neither answered our questions.

From our investigation, we found a lot of issues stem from the fact DDS hasn’t changed how much they pay regional center service coordinators since 1991.

“DDS has basically budgeted these service coordinators at $34,000,” said Tilden. “Which, obviously, isn’t enough.”

At max, coordinators are supposed to have 62 clients. For Sacramento’s Alta Regional Center, the auditor found an average of 86 clients per coordinator; or 40% more than the requirement, which makes it harder to care and provide adequate services for each client’s unique needs.

“I think 80 was about my average,” said Barbara Imle.

Imle experienced this first-hand as a service coordinator at multiple regional centers.

“Their caseloads are obscenely high and they’re already overworked and underpaid,” said Imle.

Severely underpaid as the California Auditor found DDS should be budgeting these positions at $70,000 per position.

“That’s almost double of what they’re actually doing,” said Tilden.

Many coordinators left for better opportunities. The audit found between 2020 and 2021, Alta Regional Center hired 71 new employees and 76 left.

When coordinators aren’t supported, the clients suffer – especially those conserved – because coordinators play a crucial role in limited conservatorships for people with disabilities.

While the audit’s scope didn’t include conservatorships, Imle has been digging into this niche area.

“Because we have no national guidelines requiring states to gather data and information,” said Imle. “There’s no information out there.”

Until Imle’s research. After working in two regional centers for nearly 10 years, Imle left to instead study them.

“My experience with transferring between regional centers is really eye-opening,” said Imle.

What her research found was there are 21 different ways of doing things for California’s 21 different regional centers.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Imle. “Not just to service coordination in general, but particularly (for) limited conservatorships.”

Coordinators have too much on their plates, impacting their ability to do assessments for limited conservatorships.

“[The assessment] has potential to have a lot of influence and power on the decisions,” said Imle.

For limited conservatorships of those with disabilities, the coordinator writes an assessment about the person being conserved. The assessment includes which powers the person should have taken away.

The coordinator also recommends if the conservatorship should be granted or not in their assessment. The recommendation/assessment goes directly to the probate court judge before making their final decision.

Yet DDS provides no guidance or training on conservatorship assessments for its regional centers.

“They’re virtually silent on limited conservatorships,” said Imle. “There’s no really overall discussion of what’s expected, how they’re going to do it, and what needs to be done. There’s just… nothing.”

Attorney and advocate Tom Coleman with the Spectrum Institute also found DDS has no budget designated for anything related to conservatorships.

“Examine their contracts. There’s not one word mentioned about conservatorships. There’s no money in the contract for conservatorship evaluation,” said Coleman. “What if you or anybody viewing this broadcast was told to do a job and then not given any money to do it? How good of a job are you going to do?”

With caseloads rising, Imle says many coordinators don’t have time to truly evaluate the person that may be conserved.

“They do not require in-person meetings. A lot of the assessments are written just based off reading the chart and the notes in the computer system,” said Imle.

Meaning that these assessments with the power to separate families and strip someone of their civil rights by conservatorship can't be trusted.

“There’s just a total disregard for the client’s desires,” said Imle.

She also found probate courts are part of the problem.

“Even when you write a stellar assessment that’s really going into detail and might provide alternatives, the judges don’t always read it, acknowledge it or include that in their decision making,” said Imle.

Imle observed 93 conservatorship cases in two county probate courts. Every single one of the conservatorship cases she observed was approved. None were denied.

73% of those cases were approved by the court in five minutes or less.

She also discovered all seven powers were requested and approved in most cases.

“It’s not being individualized or limited to meet the need of the individual,” said Imle.

Perhaps most concerning of all is a loophole she discovered.

“I think a lot of it has to do with bypassing the regional center assessment and cuts out one extra agency that’s going to be involved,” said Imle.

She found people being placed under general conservatorships to skip the assessment, which is only required for limited conservatorships.

“One regional center had 187 requests were for general conservatorships compared to 58 for limited,” said Imle. “That was in one year.”

Limited and general conservatorships can have powers over a person, their estate, or both. Rather than opting in or out of seven separate powers, general conservatorships strip someone completely of all their civil rights, which is why experts told us a general conservatorship should never be appointed for a person with a disability.

But that’s exactly what happened to Martin Bui.

Court documents show in 2013, shortly after arriving to California, the Bui family petitioned to be Martin’s conservator and have a bank manage his money. This was the same setup they had in the previous states they lived in prior to moving to California.

Because of the injury Martin suffered at birth, a lawsuit settlement allotted him monthly payments, which increase year after year. At the time of their move to California, he was receiving $27,000 a month and had a net worth of around $2 million, court documents reveal.

“It was an annuity basically to take care of him the rest of his life,” said James.

The court appointed a professional fiduciary to manage both Martin’s wealth and all personal decisions through a general conservatorship. This occurred after Martin’s court-appointed attorney raised concerns about the family’s handling of the money, court documents show.

“The money was all for Martin,” said James. “We just happened to live in the same house, live with him, grow up with him, he was always part of our family.”

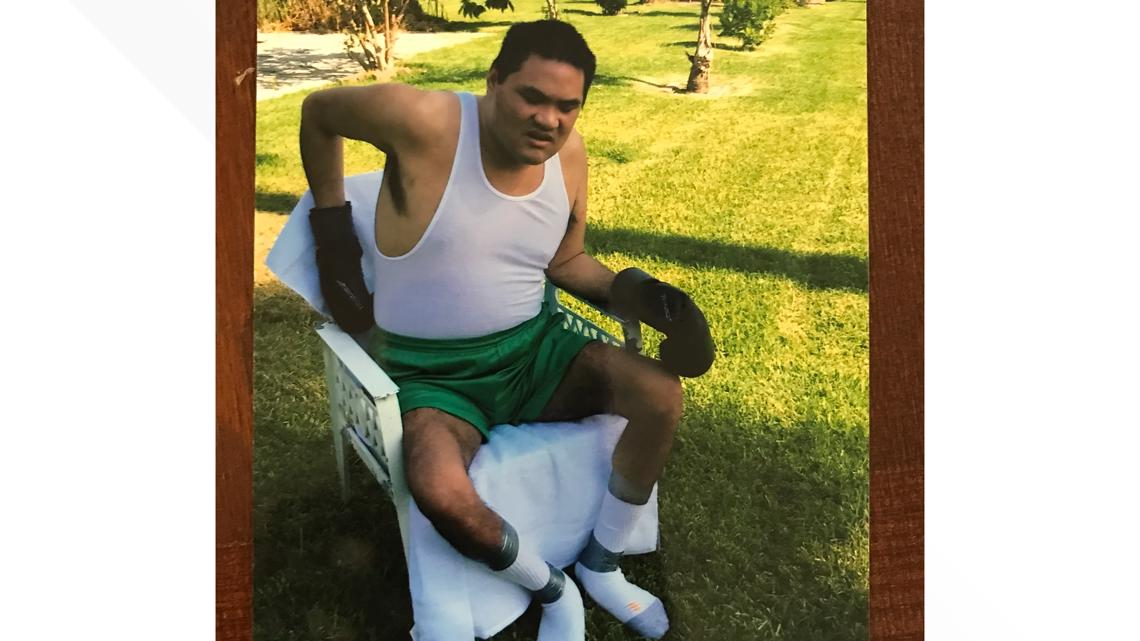

After the general conservatorship was appointed, Martin lived at home with family for a short period until he had a bad reaction to anesthesia during a dentist appointment and spent the night in the hospital.

“Then literally in the middle of the night, he gets relocated to another location and doesn’t come home,” said James. “We asked the hospital like, ‘Hey… where’s Martin?’ They were like, ‘He checked out.’ We were like, ‘How can he check out?! Who took him out?’ (We were) contacting the conservator – she wouldn’t respond.”

Rather than an answer, the conservator sent a photo.

“A photo was sent back to us with his socks rolled up (and) duct taped, boxing gloves taped to his arms, and a newspaper saying this is the date,” said James. “It was almost like he was held hostage in the 21st century.”

Boxing gloves duct taped to his skin...

James said this was so Martin couldn’t remove his clothes, like he often did because of a sensory processing disorder that makes him extremely sensitive to certain fabrics.

“He had sensitive skin and eczema,” said James.

Their mother dealt with this much differently in the past.

“She went to JOANN fabrics and made him all this special clothing so he would feel comfortable and feel lose,” said James.

When Martin was hospitalized after the dentist, court documents show the conservator said she, “seized the opportunity and removed Martin to a private residence.” She requested the family “not to visit until the client adjusts to the new routine.”

“It was like a negotiation to have visitation, as if we broke a law or something,” said James. “So we have to fight this in court. Now we have to lawyer up and we’re spending money out of pocket to fight this system that we thought was there for us.”

It's an expensive legal battle, but those representing Martin -- like his conservator, the conservator’s attorney and Martin’s court-appointed attorney -- are paid through Martin’s estate.

“So the person we’re advocating for has to foot the bill for everybody,” said James. “It makes you wonder; whose interest is at stake here?”

For the last eight years, the Bui family has continued to fight Martin’s conservatorship, even after their mother died from a heart attack.

The Bui’s had to file an ex-parte, an emergency petition, in order to get Martin to attend his mother’s funeral after the fiduciary initially refused to negotiate time.

“We would not wish this on anybody because that’s just the most horrendous (thing),” said James. “(It was not) how we thought California would be.”

Today, Martin has a new fiduciary but still lives in a care facility under a general conservatorship.

So, how do we fix this system? How do we protect people like Martin?

Coleman’s organization, Spectrum Institute, has proposed in-depth solutions for years.

“I realized the system could be significantly improved and transformed if DDS were to do its job,” said Coleman.

It’s also what the audit showed: DDS is aware of their faults.

The June 28, 2022 audit was the sixth done on DDS since 2010. In it, the auditors repeatedly pointed to problems they’ve named in past audits. Some were “especially concerning,” they said, since DDS had years to fix these issues but didn't.

The state auditor asked DDS about these problems they hadn’t fixed. DDS said they “could not explain” why many issues were not fixed.

“There’s plenty that DDS could do and they know this! We’ve told them this,” said Coleman. “We’ve told the governor this. We’ve told the Secretary of Health and Human Services this. We met with them personally… nothing has been done.”

Less than a month after our interview with the auditor, they released another audit on DDS showing a lack of oversight over how DDS oversees in-home respite services, which provide care to those with disabilities who live with their family -- showing further failures by DDS.

Department of Developmental Services statement to ABC10:

“In California, unlike any other state in the nation, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities have a right to the services and supports to help them live their most independent and productive life. With the passage of the ground-breaking Lanterman Act in 1969, the state affirmed its commitment to these rights for Californians. We at the California Department of Developmental Services have the responsibility to deliver on the assurances made by the law.

It is our obligation to hold ourselves and our system partners accountable, while ensuring that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities receive community-based services and supports that embraces choice and allows them to live with purpose and dignity. We are constantly looking to improve how we serve the whole person, all while protecting the health and well-being of those we serve.

We are striving to create effective, culturally responsive, and efficient services. We have advanced this vision by the historic investments made over the last two years that, when put together, drive us toward a system of value-based services and supports, where our main objective is quality and better outcomes.”

Department of Developmental Services response to our questions:

“DDS does not actively seek conservatorships. In all instances, the Department of Developmental Services’(DDS) involvement in the conservatorship process begins with a submission by a third party requesting that the Director of DDS become conservator of a person with developmental disabilities. DDS only decides to petition to become conservator when clear and convincing evidence shows that a conservatorship is needed to protect the consumer’s health, safety, or well-being. The submission can come from a variety of sources, such as the courts, a regional center, a law enforcement agency, a family member, the county public guardian, the consumer’s court-appointed counsel, local adult protective services, or any other person interested in the consumer’s health, safety, or well-being. The conservatorship process is a court-based, legal process. As such, DDS has the legal burden to present conclusive evidence to a judge demonstrating that the conservatorship is necessary to protect the person’s health, safety or well-being.

Family members can and do participate in the judicial proceedings that decide whether a conservatorship petition should be granted, the scope of the conservatorship, and whether the Director of DDS should be appointed as conservator. Furthermore, a court-appointed counsel is part of this process. These are officers of the court appointed by a judge to represent the interests of the proposed conservatee. These counsels are completely independent of DDS and do not receive any funds from the Department. Court-appointed counsel have a fiduciary duty to act independently and in the best interest of the proposed conservatee to determine whether a conservatorship is necessary and who, if anyone, should serve as conservator.

DDS does not seek to become a person’s conservator without a third-party submission having first being made and thoroughly vetted. DDS conducts a comprehensive, detailed inquiry when it receives a conservatorship nomination. DDS will not seek to become conservator if there are alternate, less restrictive means to protect a consumer’s health, safety, or well-being. DDS also will not seek to become conservator if there is a family member, friend or other close person in the consumer’s life that can protect the consumer’s health, safety or well-being. DDS has a legal and moral obligation to protect the consumer no matter the desires or objections from family members.

It is important to understand that under state law every regional center consumer participates in the development of an Individual Program Plan (IPP) that identifies the supports and services the person needs. An IPP is developed regardless of the legal status of individuals. The amount of funds spent on a consumer is based on costs for the supports and services identified in the IPP, and not on any other factor such as whether a conservatorship is in place. Thus, absolutely no additional funds are spent simply because a consumer is subject to a conservatorship by DDS. In addition, neither DDS nor the regional center receives any additional administrative funding for individuals who are conserved versus those who are not conserved.”