The Price of Care: Investigating California Conservatorships

ABC10 dives into the systemic issues of conservatorships in California and what's being done to regulate this $13-billion-dollar industry.

ABC10/KXTV

Many have heard of conservatorships recently by way of Britney Spears or the Golden Globe winning Netflix film, I Care a Lot. One year in the making, this ABC10 Originals five-part series, “Price of Care: Investigating California Conservatorships,” by investigative reporter Andie Judson, dives into the systemic issues of fiduciaries and conservatorships in California and what's being done to regulate this $13-billion-dollar industry.

In this series, Judson explores how a powerful industry created to assist those who cannot care for themselves -- granting them power over choosing what people can eat, who they see, where they live, as well as their money and assets -- has little oversight from state regulators, and how many believe this opens the door to some benefiting themselves rather than the person their supposed to care for, typically an elderly person under conservatorship.

🡆 Follow our 5-part series: WATCH EPISODES | SERIES BACKGROUND | ALL ABOUT CONSERVATORSHIPS

Episode One 'Civil Death'

Many have heard of conservatorships in headlines recently but the concept of a conservatorship, or guardianship, dates back to Roman times.

Today, conservatorships are when another person is court-appointed to help someone who cannot take care of themselves. It’s a powerful position. When a conservator is appointed, they gain control over another person’s life --what they eat, who they see, where they live, what medical care they receive —all while handling their money and assets.

As the baby boomer generation ages, conservatorships are becoming more common for one of our most vulnerable demographics: our elderly. And while many conservatorships do help those who need it, our year-long investigation found a system that controls a massive amount of other people’s money – just under $13 billion in California alone -- as well as personal freedom, with little oversight from state regulators, opening the door to potential financial, physical and emotional abuse.

Episode Two 'The Patterns of Control'

Isolation from family and friends, depletion of estates and a group of the same attorneys, conservators, medical providers and caregivers working together. These are a few of the patterns ABC10 investigative reporter Andie Judson found in some cases in her year-long investigation into California conservatorships including a Sacramento area family business – mother, son, and daughter – who control nearly $277 million dollars of other people's assets combined.

This episode dives deep into an industry that many believe is benefitting its members, rather than the person it’s supposed to care for, typically an elderly person under conservatorship.

Episode Three 'The Old Boys' Club'

Conservatorships give control over someone’s life, money and assets to another. And if families aren’t getting along, the probate court usually will appoint a third-party fiduciary to be conservator. It’s a life-changing decision that’s often made quickly; probate courts throughout California are inundated, with judges seeing hundreds of cases in a week, sometimes dozens an hour.

This episode digs into how our probate court system works and narrows in on the happenings of the Sacramento County Probate Court, one that multiple insiders and experts have referred to as a “good old boys’ club” throughout ABC10’s year-long investigation. Many believe it’s a club that’s benefitting its members, particularly through loopholes that some believe are leading to corruption in conservatorships.

Episode Four 'The Fight for Accountability'

The job title of a fiduciary is broad and powerful. Fiduciaries are trained to manage their client’s wealth, well-being, and assets. It’s also the certification needed to be a conservator.

After abuse was exposed in California conservatorships, the state created the Professional Fiduciary Bureau under the California Department of Consumer Affairs. The PFB was set up to regulate “non-family member professional fiduciaries.”

But the state entity that was created to provide oversight and protect clients has never - once - issued a citation for abuse. Abuse that could be going under the radar, as the bureau only has one investigator to look into the hundreds of detailed complaints they receive.

Our investigation shines a light on the failure of a bureau that was set up to ensure the protection of fiduciary clients, many who are society’s most vulnerable.

Episode Five 'Set Up for Failure'

ABC10 investigative reporter Andie Judson's year-long investigation found an industry with little oversight from state regulators opening the door to potential abuse. So, what’s being done to regulate the $13 billion conservatorship industry in California? This episode examines legislation that’s currently being debated within our state capitol to answer the question of how to prevent conservatorship abuse.

Episode One: 'Civil Death'

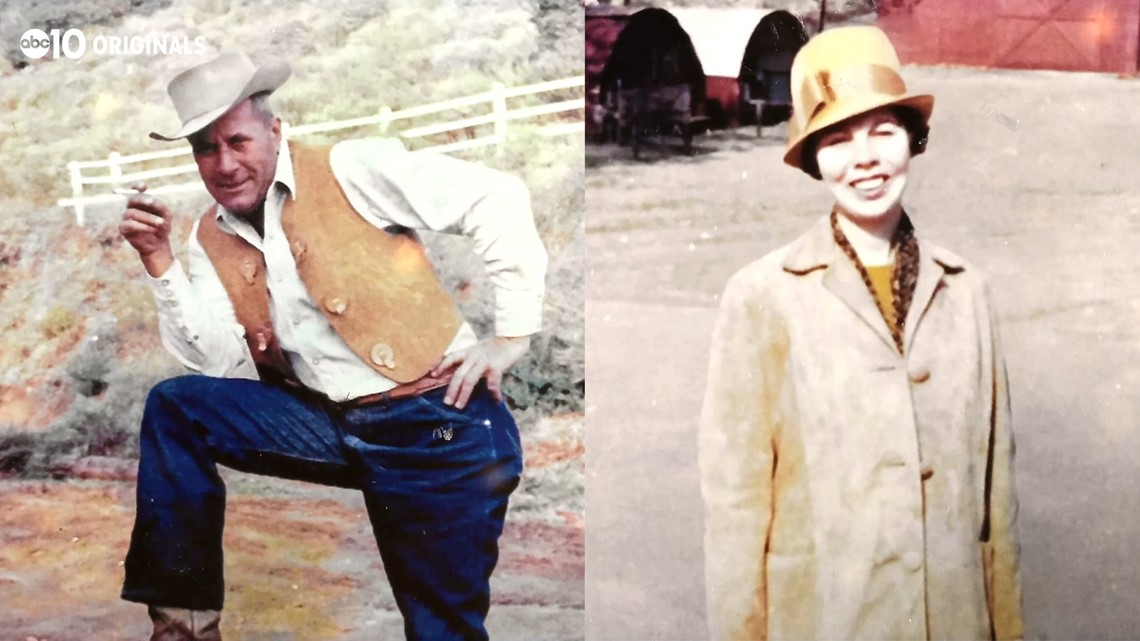

During the 1950s, Linda Duncan was a waitress at the southern California restaurant staple, “Donna’s House of Pancakes.”

When one of their regulars, Calvin Duncan, came for breakfast, he was hard to miss.

“My dad lived in the era of Rat-Pack. He was the same age as Frank Sinatra, so he would dress like that. He would have his little pocket square and his hat at a tilt, with his suit and tie,” said Saal. “[My mom] said she could see him coming in [his] really beautiful pink Cadillac.”

Saal said her mother was “a cute young thing” who had been an extra in a few Hollywood films. Her father quickly took a liking to her.

“His story is that she followed him home to the ranch and never left,” said Saal. “It was a classic love story.”

This 250-acre ranch in Malibu was where Linda and Calvin raised their three children. Saal describes her childhood as idyllic, saying she now orientates herself around the beach, much like her mother did.

But as Calvin was 30 years older than his wife, Saal said he was aware of the reality his wife would likely live longer than he would.

“My dad really set her up in her retirement so that she would have everything she needed,” Saal said.

That’s why, after years of marriage, the couple decided to move from the ranch to a home in Camarillo.

“[It was] designed for somebody to age very gracefully. It was all one level,” Saal said. “She spent so many years working on the garden… We always assumed mom and dad would spend their last years in this beautiful view house – and my dad did.”

But Linda didn’t.

Twenty years after her husband passed, Linda no longer lives near the ocean, tends to her garden, or even spends much time outside.

Linda has been placed in an assisted living facility in Auburn, hundreds of miles from the home her and her husband shared.

Saal said she’s there against her wishes.

“I think she’s unhappy in that situation and she much would prefer to be in her own home,” said Saal.

ABC10 joined Saal on her visit with her mother on August 13, 2020, so we could hear directly from Linda.

Linda described her own situation as tragic and sad, as well as recollecting past memories of the ranch.

“I had the most wonderful life, and to be shut down here like this… it’s just kind of a sad situation,” Linda said. “It wouldn’t be so bad if I could come out. It’s a tragedy, I think.”

Linda also said she believed she was going to “deteriorate in here.”

The reason Linda cannot return home is because she’s under a conservatorship.

A conservatorship is when another person is appointed by a judge to have legal authority over someone’s life. While there are different types of conservatorships, depending on the conservatee--such as an LPS conservatorship for mental health--a majority of conservatorships are put in place for aging adults suffering from dementia or other health issues that prevent them from taking care of themselves.

Conservatorships have made headlines recently with the popular New York Times documentary, Framing Britney Spears, and Netflix’s Golden Globe winning film, I Care a Lot.

But conservatorships aren’t new.

“The idea of a conservatorship, or guardianship as it’s called in most states (besides California), goes way back into Roman times,” said Linda Kincaid, Co-Founder of the Coalition of Elder & Disability Rights, an organization focused on California conservatorships. “It’s the idea that someone gets appointed to help take care of a person that for, whatever reason, cannot care for themselves.”

The position of a conservator is powerful.

“This process is going to take away your mom’s rights,” Kincaid said. “If you become her conservator, now your mom enters into what some people call, ‘civil death.’”

While family members can be appointed conservators, if a court appoints a third-party conservator it will be a fiduciary. A fiduciary is the profession of handling other people’s money and assets. It’s also the specific certification needed to become a third-party conservator.

According to the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, this industry manages just under $13 billion of other people’s assets in California alone, and this number may be increasing. Conservatorships could be on the rise as we’re entering the “silver tsunami,” a term describing the growing baby boomer generation.

By 2025, the number of Americans aged 65 and older will increase by 60 percent, the United States Census Bureau reports.

By 2035, in California alone, there will be more 65-year-olds than 18-year-olds, the California Department of Finance projects.

The legal responsibilities that come with aging are extremely familiar to Michael Hackard.

As an attorney, Hackard got his start in land-use law. But when trust issues came up in his own family, he felt helpless and confused despite having an extensive legal background.

That’s why he changed specialties to trust and estate law, and after 40 years, he’s a trusted expert in this field. But it’s not just his clients that he wants to help. Hackard posts weekly YouTube tutorial videos and wrote the book, The Wolf at the Door: Undue Influence and Elder Financial Abuse. These efforts are aimed at helping anyone navigating the confusing world of conservatorships and abuse.

“There are two types of conservatorships,” Hackard explained.

A conservatorship of a person means someone oversees all personal aspects of your life. Everything from what you eat, where you live, and your medical care to who you’re able to see.

“That is different than the conservatorship of finance, or financing,” said Hackard.

The other type of conservatorship is of an estate, where another person has full power over all your financial affairs and assets.

“Takes over everything that you own, and all the rights you have to ownership,” said Hackard.

And these two types of conservatorships aren’t exclusive.

“They’re often paired together. In my view, when they are paired together is when you start seeing issues… the conservatee often becomes invisible because it’s as though they’re in their own prison in a way because the conservator or a person controls all access to them.”

It’s a sentiment Julie Doherty said she feels.

Every Saturday, Julie drives two hours from Marin County to Sacramento, then two hours back. It’s four hours of driving for 30 minutes of visitation with her mother.

Her visits are at the home where she grew up. At the time of our investigation of this story, due to COVID-19, Julie had to remain outside, only permitted to see her mother through a window. COVID also required that what were initially three-hour visits to be limited to half an hour.

Doherty isn’t allowed to stay five minutes past visitation time or arrive early.

“We’re not allowed to drop in, ever,” said Doherty. “There was no flexibility whatsoever. We also weren’t allowed to bring any friends with us or any food or drink.”

Rules she must follow, even on special days like her mother’s birthday.

“This shouldn’t be allowed to happen to anyone,” said Doherty. “People who are incarcerated get more visitation time than my mother does.”

But this limited access wasn’t always in place, in fact Doherty used to take care of her mother – Carole Anne Elzey. But a $300,000 loan changed everything.

“I was purchasing a condominium up in Marin County,” explained Doherty. “And my mother agreed to provide an equity loan against her home in order for me to obtain my mortgage.”

Doherty said, and accountings show, she paid back the $300,000 loan per the loan’s agreement.

The loan sparked disagreements between Doherty and some of her four other siblings, resulting in their mother being placed under the conservatorship of fiduciary Carolyn M. Young.

It’s something Doherty is adamantly opposed to.

“I will never not be upset that we have this third-party conservator,” said Doherty.

But the family is divided.

ABC10 reached out to each sibling to get their side.

Doherty’s sister, Alison Schofield declined our request for an on-camera interview but sent us multiple emails advocating for Young’s placement as conservator and questioning Julie’s motives, saying by hiring Young they “chose to protect our mother and secure a fiduciary.”

Alison told us, as well as court documents reveal, that issues around visitation were occurring before the conservatorship was in place. She also said, “Julie Doherty is 100-percent the reason our family has Carolyn M Young fiduciary overseeing our mother’s estate.”

Their brother, James Doherty, never responded to ABC10. However, he appears to be in favor of the conservatorship according to court documents he filed objecting to Julie as conservator and backing the appointment of Young.

Their other sister, Michelle Vinall, responded in an email saying she has formed cynical opinions of the conservatorship of their mother and that she agrees with Julie that, “Young and co., including all those interconnected from the judicial system, and attorneys, down to the concierge doctors and nurses” are all feeding from a “parasitic trough that will deplete enough assets that should have been enough for three lifetimes.”

Despite ABC10’s numerous requests over the course of months, Carolyn Young would not grant us an interview. But she did answer some of our questions in writing.

She provided us with a list of legal actions taken in Elzey’s case. She also provided the following statement to us:

“Since the California Labor Laws changed in 2014, 24/7 care in a client’s home costs $25,000 per month, and most trusts cannot sustain that expense. This rate computes to $300,000 per year.

In addition to direct care, a review of public records (included in the many public documents I have provided to you) indicate the following legal actions. With the exception of the first and second accountings, which are required by law, none of these actions were initiated by me.”

The fifth sibling, we never received a response from.

As for what their mother, Elzey, thought of the conservatorship herself, it’s shown in the court investigator’s report provided to us by Doherty. The report says that after interviewing Carole, they determined that she was “opposed to the appointment of the proposed conservator.”

“I started battling this fight just to be able to see my mom,” said Doherty. “I just want to be able to see my mom.”

Issues between family members is one of the oldest predicaments there is, even being addressed in the Bible, Luke 12:13:

“Someone in the crowd said to him, ‘Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.’”

“Jesus replied, ‘Man, who appointed me a judge or an arbiter between you?’”

And over 2,000 years later, sibling disagreements are still an issue. But today, families go to probate court for help.

“Where it gets sticky is suppose that your mom needs help and you and your siblings are at war with each other which, unfortunately, is so often the case,” said Kincaid. “The court isn’t going to appoint one sibling or the other to have control over mom when there are just these huge objections flying back and forth.”

So, the court appoints a professional fiduciary to serve as conservator.

“Someone who is supposed to put the interest of the conservatee above their own interest,” Hackard explained.

Acting in the “best interest” of the conservatee is a term used repeatedly in Probate Code. But the interpretation of "best interest" is in the hands of the conservator, and some advocates believe it can make for a slippery slope.

For instance, the visitation schedule for Doherty and her siblings is what’s best for their mother, according to the medical doctor hired by the conservator, Young.

But Julie finds it cruel.

“I don’t want visitation. Visitation implies just that, a structured date and time – a beginning, middle and end. I want unfettered access to my mother. I want to spend the night. I want to be able to hold her hand,” said Doherty. “I want to be able to sit next to her and reassure her everything is okay, just like most families do with their loved ones.”

Court documents reveal disputes about visitation were occurring before the conservatorship was in place. In an ex parte petition for order to “allow temporary conservator to employ independent caregivers for conservatee and terminate Julie Doherty as caregiver,” filed by attorney Todd Robie, who represented Julie’s brother James, it stated, “during the period Julie Doherty has been providing care, Julie Doherty has impended visitation of the conservatee’s other children with the conservatee. The Declaration of Carolyn M. Young cites specific examples of Julie Doherty’s interference with other children’s visitations.”

No matter how you look at it, you can see that time with their mother is being impacted. It’s time that may be running out. Elzey is 87 and has multiple chronic conditions, including dementia. In February 2021, she was admitted to hospice care.

“She’s had rapid decline… in the last few weeks she has become non-verbal,” Julie said during an interview in February. “I’m never going to agree with Carolyn Young’s placement as conservator.”

But once a conservatorship is appointed, it can be very difficult to terminate. Part of it is because of the cost.

“When and if I take on a conservator, that conservator is not using his or her own money… they’re using the conservatee’s money to defend,” said Hackard.

The Probate Code names a procedure to file a petition to terminate a conservatorship. But Kincaid says you’ll most likely be opposed by the conservator.

When we asked why a conservator gets a say when they’re supposed to be a third-party, Kincaid put it simply: money.

“Because it pays so well. Conservatorship is about money,” said Kincaid. “It’s about billable hours and the more they can keep you coming into court.”

When fighting a conservatorship, multiple parties come before a judge. Kincaid said this can include the conservator, the conservator’s attorney, the conservatee’s court-appointed attorney, a guardian ad litem as well as experts. All of these parties can come before a judge to decide what’s best for the conservatee and can oppose the termination of a conservatorship.

“They all get paid from mom’s estate,” said Kincaid.

According to Elzey’s conservatorship accountings filed through the court, between November 2017 and January 2020, the Sacramento County probate court approved over $265,000 in fiduciary and legal fees for Young, Young’s attorney and the conservatee’s court-appointed attorney. This included a nine-day trial where Young and her attorney defended the conservatorship, with Young prevailing.

This sum doesn’t include some siblings’ attorney fees that were later paid by the estate.

Between court fees, the price of in-home caregiving and the cost of living, accountings show the estate has a total disbursement and has been charged over $1.5 million in the last four years since the conservatorship began. The second accounting shows just under $1.3 million has been transferred from Elzey’s trust.

Young responded in-part to our question about these costs saying, “Since the California Labor Laws changed in 2011, 24/7 care in a client’s home costs $25,000 per month, and most trusts cannot sustain that expense. This rate computes to $300,000 per year.”

She also provided ABC10 with a list of nine legal actions and said, “with the exception of the first and second accountings, which are required by law, none of these actions were initiated by me.”

The following is the full list of legal actions Young included in her response:

“Objections filed to the Conservatorship resulting in two mediations at Weintraub”

“Petition filed by daughter Julie to be the Conservator”

“Eleven motions filed by Julie opposing my actions… all denied”

“Appeal filed in Court of Appeals… eventually withdrawn”

“Mediation at Court of Appeal”

“Production of documents and many depositions by Julie’s attorney”

“A nine day trial heard by Superior Court Judge. Ruling in favor of me.”

“Objections filed to CMY accounting, resulted in several hearings, mediation in Superior Court Judge’s chambers, set for two day trial resulting in preparation of trial briefs; an additional two days in Superior Court with a judge mediating the issues; eventually taking two years for accountings to be approved”

Julie Doherty said the worst part, to her, isn’t her “mother losing her assets” but that her “mother has lost her family.”

“I’ve been robbed of time with my mom,” Doherty said.

But even if you think your family’s wishes are set via your trust and will, Saal – who we first introduced you to back at the beginning of the story – says to think twice.

Saal said herself and some members of her family discovered all her mother’s estate planning documents were changed.

We joined Saal’s visit with her mother to hear directly from her on August 13, 2020. That was two days before she was evaluated by a doctor, first on August 15, 2020 and again on August 21, 2020. According to the doctor’s evaluation provided to ABC10 by Saal, he declared her incapacitated saying she has “severe cognitive decline” and that she doesn’t show “knowledge that she’s being conserved.”

But according to court records, Linda’s cognitive slip happened over the last year, between September 4, 2019 when estate planning documents were changed and September 9, 2020, the day the doctor’s report was released following his evaluations in August.

This means in September 2019, a year before being declared incapacitated, Linda signed estate planning documents appointing Carolyn Young and her son, Zach Young, to serve as trustee and potential conservator of the estate, if warranted.

“A new will was created, our family trust was changed and a new trust was created,” said Saal. “There were new trustees put in place of mom’s trust and she had a new power of attorney for healthcare and a new power of attorney for finances.”

Linda’s medical evaluation said her legal counsel, attorney Todd Robie, asserted she had “relevant civil capacities to create these estate plans.”

“All of this was very surprising to our family because for the past 22 years, my mom has had the same estate planning documents,” said Saal. “We just assumed that it would be that way and left alone the way that my mom and dad had set it up and intended it to be.”

When we asked Young about changing client trusts, she noted how this must be done through a court petition and order, giving beneficiaries the ability to object and saying changing the trust is “extremely rare.”

When we asked Hackard about changing trusts, he said it can be common.

“They petition the court for the change and it’s fairly common. Most of the time it might be more benign, that there’s some reason to do it. Maybe there’s a tax reason. But it can also be terrible,” said Hackard. “It can be cutting out other beneficiaries. And it’s [something that can be] a projection of power. 'I am the conservator. I can do this.'”

Conservatorships were created to assist and protect our most vulnerable population: our elderly. And many of them do. But our year-long investigation found that California’s multi-billion dollar conservatorship industry is powerful, with little oversight from state regulators, opening the door to potential abuse.

Episode Two: 'The Patterns of Control'

“Her and my dad made this trust, and my mother thought it was set,” said Jamie Lamborn. “It was going to be okay.”

Lamborn’s mother passed away in August 2000, leaving behind her stepfather, Clarence Johnson, who went by the nickname “Jack.” Lamborn regarded Jack as her father.

“I was very close with my mom and dad… both of them. [In the timeframe] of three years, I counted two nights I believe I stopped missing by,” said Lamborn. “[Jack] was always my rescuer.”

But when Jack’s mental and physical abilities started declining, as trustee, Jamie knew it was time for her to become his rescuer.

“I knew my mother and father trusted me to take care of them and I think that’s one of the reasons why my mother wanted me to be trustee,” said Lamborn.

But Lamborn said she didn’t fully understand the responsibilities of being a trustee. So, she sought legal help and guidance. She said her attorneys immediately began recommending that she hire a fiduciary.

“Every time I was around him it was, ‘Give it to a private fiduciary. They’ll take care of it,’” Lamborn recalled.

Lamborn estimates it was a month after she initially hired attorneys that she decided to abide by their advice and relinquished her role as trustee, as well as granted a conservatorship of her father to a fiduciary they recommended: Carolyn Young.

“They told me when Carolyn Young becomes conservator, she takes care of everything with Jack,” said Lamborn.

It’s a similar story for Catherine.

“My dad’s attorney, Todd Robie, was trying to suggest to my dad maybe they hire this woman, Carolyn Young, to help them with their finances,” said Catherine.

While Catherine’s situation is different, it ended the same way Lamborn’s did, with her parent being placed under a conservatorship in 2013.

Despite her mother passing away in 2016, Catherine is still in litigation. Because of this, she requested we not include her family’s last name.

Catherine said her father appointed one of their caregivers to serve as co-trustee because Catherine lived in another state and the caregivers became like family to her parents.

“I was not living here,” said Catherine. “That was really my dad’s big concern was making sure that my mom’s caregivers wouldn’t leave her.”

The other trustee was their granddaughter, who was age 25, Catherine said. She said her father’s attorney encouraged both trustees to enact a conservatorship.

“The odd thing is this could still take place when my mother was against it – my brother, myself,” said Catherine. “So direct relatives more so. That’s just the court system.”

Catherine said for the four years the conservatorship was in place, Young saw her mother a total of three times.

ABC10 asked Young about Catherine’s claim, she responded in-part saying she could not “speak to this specific case as these matters are confidential,” but generally speaking conservatees are seen once a month by herself or her staff.

Someone can be placed under the conservatorship of a fiduciary for a variety of reasons, including family disagreements. But another common way such conservatorships are instated is through the recommendation of attorneys.

“I think a lot of attorneys will refer over to fiduciaries,” said Hackard. “I do have my favorite fiduciaries. But they’re my favorites because I think they actually look out for the clients.”

But some are concerned about fiduciaries that look out for themselves, and those who work with them, rather than the client.

It’s a pattern we found in documents from the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, including:

Fiduciaries David and Susan Katra in Santa Clara County surrendered their licenses, with the bureau alleging they committed a number of crimes, including serving as general contractors themselves and costing the estate more because the work performed on their clients’ home was poorly done.

Fiduciary Richard Cox in Plumas County purchased shares with funds from client’s trusts in a company he owned.

Fiduciary Sally Cicerone in Orange County paid herself $14,519 and her attorney $28,293.70 from a client’s trust fund after she had been removed.

It’s something Jim Marshall said he saw in the Sacramento County probate court in the 29 years he served as a court investigator.

“The corruption is to frustrate the intent of the trustor, the person who is relying on another to protect them and protect their estate and see that their wishes are upheld during and after their lifetime,” said Marshall. “However, not all fiduciaries are doing that.”

When we asked Marshall if he believed that kind of corruption is happening in the Sacramento County probate court system, he said yes.

“I think that once you amass tens of millions of dollars in your portfolio, it gives you buying power and you can use that to purchase medical services, doctors evaluations and all kinds of things,” said Marshall.

ABC10 began our investigation in 2020 after several people reached out with criticism of Carolyn Young, one of the most well-known and powerful fiduciaries in Northern California. They had similar stories and concerns about her practice, which includes her two children, Zach Young and Lindsay Bowman, who are fiduciaries in their family business.

As our investigation progressed over the course of a year, we learned there are system-wide issues across California.

As we’ve already established with attorneys, one of the patterns we encountered is the same professionals being involved in conservatorship cases over and over… but we also found a pattern of the same medical providers.

Pattern: Same professionals

It’s one of the many patterns found in multiple books including, “Guardianships and the Elderly: The Perfect Crime,” “Guardian Angels, Inc.” and “Guardianship Fraud.”

It’s also found in studies from the United States Government Accountability Office as well as the National Center for State Courts.

Changing medical providers is something Richard Calhoun, Co-Founder of the Coalition of Elder & Disability Rights, said is common – and concerning – in conservatorships.

“Most of the time their doctors get changed. Why is it that they’re going to a doctor that has never seen this person before? Why aren’t they going to a family physician when they have a family physician?” said Calhoun. “Those are the questions that really should be being asked.”

Doctors evaluate the elder’s capacity, a key in the conservatorship process as permanent conservatorships aren’t fully granted in court until it’s proven that the elder cannot care for themselves.

“My mother was a remarkable woman. She had a zest for life. She was a fighter and she was amazing,” said Carol Kelly. “She had no fear… she traveled the world on her own.”

After an anonymous call was made to adult protective services saying Mary Jane Mann was at-risk of abuse from one of her daughters, Carol Kelly, she was placed under the temporary conservatorship of Young after Young filed a petition in November of 2006.

“My mother was fully competent. She was driving. She went through the driver’s safety office and went through a long procedure where you have to get your doctor to say it’s okay for you to drive,” said Kelly. “Then take the behind the wheel test. She passed with 100 percent.”

Carol and her sister were at odds--her sister for the conservatorship, and Carol against it.

Records to the case provided by Kelly show Mann underwent three independent evaluations from different doctors between 2007 and 2008, after the petition for conservatorship by Young had been filed.

“A clinical psychologist, a clinical neurologist, her own physician. She was not only average, she was way above for her age. She was functioning completely on her own,” said Kelly. “Young did not want to accept those findings. She would say, ‘Well, we need to have her evaluated by somebody we’ve selected.’”

According to court documents filed in 2008, Mann’s other daughter and Carol’s sister, who was in favor of hiring a fiduciary, wanted another evaluation done, specifically requesting in court documents that it be done by two doctors, one of which we found has worked with Young repeatedly.

Kelly said her mother refused to have another evaluation done in 2008.

“It would be in their best interest if she had dementia,” Kelly said.

Young responded with the following statement:

“There is no basis in fact for Carol Kelly’s “opinion.” I was appointed on this case approximately 17 years ago. Daughter Monica Mann, with Ed Corey as her attorney, petitioned the court for Dr. Schaffer to perform an evaluation of her mental capacity. It is an insult (and slanderous) to infer that this highly respected Psychiatrist would make a determination of incapacity for the financial benefit of CMY Fiduciary Services.”

Medical evaluations that are submitted to probate courts throughout California are crucial to the appointment of a conservatorship. However, some of the medical evaluations ABC10 obtained and reviewed were conducted by doctors with PhDs in neuropsychology, geropsychology and psychotherapy, not medicine.

While these types of doctors are well-trained and educated, Hackard prefers working with medical doctors because of how they conduct evaluations. He provided the following statement:

“Physicians are taught to differentiate between two or more conditions which share similar signs or symptoms. This is called 'differential diagnosis.' Physicians will identify this list of possible conditions by the person’s medical history, self-reported symptoms, physical examination findings, and diagnostic testing.

This is very important in the conservatorship setting because dehydration, thyroid, kidney, liver, heart and lung problems, urinary and chest infections, drug toxicity, and strokes can produce dementia-like symptoms but not be dementia. Delirium is usually reversible if the underlying cause is treated. Dementia is not reversible.

Physicians are trained to consider whether an underlying illness, other than dementia, may be causing the patient’s disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness.

A significant difference between psychologists or PhDs and physicians is that licensed physicians, particularly psychiatrists, are more likely to use the medical model to assess mental health problems. This is, of course, critical is assessing elders because a significant percentage of the elder population have chronic diseases and conditions. Psychologists and PhDs lack the training and licensing to identify chronic illnesses that may be producing dementia like symptoms – symptoms that are reversible if delirium is caused by underlying treatable condition.”

Doctors can also play a role in how often a family gets to see the person who is under a conservatorship.

Much like Doherty, Catherine also had visitation enforced following the recommendation of a medical professional.

For Catherine’s mother, court documents show a nurse, who we found has worked with Young in at least three other cases, evaluated her mother. This evaluation was used to put visitation time in place saying it was in her mother’s best interest.

“They were trying to say that I was presenting a tense environment for my mother,” said Catherine.

In the evaluation, the nurse alleged Catherine was causing her mother to have food depravation, sleep depravation and forced exercise as well as noting “this just seems abusive.”

Catherine’s neighbors who knew the family for over 30 years wrote a letter to the court saying they found the allegations of abuse “unfounded and false,” and that Catherine and her mother’s relationship had always been loving.

But following the evaluation, visitation was enforced.

“An hour. An hour a day,” Catherine said. “I’m having to go to the door to visit my mom and they won’t let me in because it’s after 8 p.m. I’m like, ‘Since when can I not visit my mom?’ And they’re saying, ‘No. You can’t.’ My mother is crying, ‘I want to see my daughter, I want to see my daughter.’ I mean… it was so heartbreaking.”

Catherine wasn’t okay with limited access to her mother.

“And so my last days with my mom were fought in court,” said Catherine.

Pattern: Isolation

Isolation is a pattern found in separate studies conducted by the Government Accountability Office and National Center for State Courts. The latter found that some “persons under conservatorship were isolated from their families [and] neglected.”

As co-founder of the organization Coalition of Elder and Disability Rights, Kincaid has reviewed hundreds of conservatorship proceedings throughout California.

“From what I’ve seen the very best way to keep those billable hours running up is to isolate the conservatee,” said Kincaid. “Because if your mom is taken away and you’re not even allowed to see her… you’re going to keep fighting and fighting and fighting with everything you have to your last penny to try to get to see your mom, and to try and protect your mom.”

Specifically, with Young, when we asked her about visitation, she responded with the following statement:

“At all times, the health and safety of my clients are my primary concern. I continue to follow the CDC Guidelines, as well as the recommendations of the doctors, and the orders issued by the court.”

Conservators have the ability to determine whether their conservatee should be moved into an assisted living facility or if they can remain in their homes, given they can afford caregiving.

A pattern we found in documents from the Professional Fiduciary Bureau was multiple fiduciaries hiring people that would benefit from these services themselves, not the client. For example:

Fiduciary Michael Patrick Cunningham hired his future son-in-law as caregiver but wrote into the agreement that the son-in-law would not “pick up the client” if they fell or help in “any medical capacity.” The bureau’s report said hiring his son-in-law was for the benefit of Cunningham’s family, not the client.

Fiduciary Dawn Akel in Sacramento County “did not hire a licensed agency” to provide care but instead “hired her brother and office staff member, both of whom had no previous caregiving/companion training.”

Professional caregivers also benefit from this $13 billion dollar industry.

It’s something Marshall attests to.

“After I finished my stint as a probate court investigator, I opened up care homes and my relationship with Carolyn (Young) was very beneficial to my business growing,” Marshall said. “Carolyn’s [clients] were proportionately 70-percent of the clients there… We had an implied contract that we could work together collaboratively and to the benefit of the individual.”

But Marshall said he saw some concerns arise around certain actions.

“Where it got tricky for me as an employer, was that Carolyn wanted us to have our employees oversee the conversations with a daughter that was allegedly creating problems,” said Marshall. “So, we became a police of sorts.”

ABC10 asked Young about instructing employees to monitor family member visits. Young responded with the following statement:

“In my 35 years as a professional Fiduciary, this has occurred only once, and was done as a result of a court order directing the supervision.”

Pattern: Depletion of Estate

Monitored visitation can lead to another pattern: depletion of estate.

With Catherine, we showed you that fighting the rules put into place for visitation can be expensive – but also visitation, when monitored, can add cost.

“My mother had to pay to see her own children,” said Doherty. “According to Carolyn Young’s letter from four years ago, it stated that everyone’s visits from neighbors and friends would have to be supervised and monitored. And then my mother’s estate would have to pay for that.”

Which also created more isolation, Doherty said.

“So even my own mother’s friends who lived down the street wanted to see her but they didn’t feel like my mother should be charged for seeing her own friends,” said Doherty.

Marshall said when he expressed unease about the stewardship of Carolyn M. Young Fiduciary Services, it was the beginning of the end of his business.

“So, the gloves were off,” Marshall said. “If they brought me in, they could take me out.”

Marshall said Young gave 30 days’ notice, then pulled all her conservatees out of Jim’s homes 10 days before Christmas.

“Everyone had their Christmas presents under the tree,” recalled Marshall. “But to see them shuffling out… [some had] severe dementia. The confusion and the disorientation.”

Marshall described some asking, "Why are we leaving? Why do we have to go?"

When we asked Young about moving her clients from Creative Solutions, Marshall’s business, she responded with the following statement:

“At one time, I had a number of client’s living in Jim Marshall’s Creative Solutions Care Homes. It was brought to my attention that Mr. Marshall was having serious financial issues. With that knowledge, I felt it was necessary, for the safety of my clients, to remove my clients from Jim Marshall’s care. Shortly thereafter, I became aware that Mr. Marshall had filed for bankruptcy. This fact can easily be verified in public records.”

But Marshall said it was the removal of Young’s clients that caused him to close his doors, then file for bankruptcy two weeks later.

“If I had known I would’ve seen the consequences of these people being marched out, I wouldn’t have raised it. I would’ve stayed in line,” said Marshall. “I would never have inflicted this kind of pain on people who don’t deserve it… I can’t get rid of those images of the true victims that suffered.”

Pattern: Autocrat and disappearing

“I think a red flag for a conservator is someone who is an autocrat,” said Hackard. “That somehow they feel that once they’re in control of this person, that they’re in total control.”

But the other red flag for Hackard is the conservator disappearing.

“That’s an enormous red flag – and again, I can think of many times people finally say, ‘I’m going to go to that conservator’s office and try to talk to that conservator since they won’t return my call,’” said Hackard.

Difficulty in reaching fiduciaries is named in a study on conservatorship abuse conducted by the Government Accountability Office, and found in court documents from the Professional Fiduciary Bureau.

In particular, filings from the Professional Fiduciary Bureau show Ronald Bradley Olund, a fiduciary whose license was later revoked, had a “voice mail message box that was full on several occasions and that family members “could not reach” them.

Inability to reach a fiduciary is something Gabe Meyers experienced as a client of fiduciary Akel.

“When we first hired her, issues began to arise,” said Meyers. “The ability for me to make contact with her became extremely strained.”

Documents from the fiduciary bureau reveal Akel failed to maintain a system of checks and balances as well as failed to pay several bills for a client.

We reached out to Akel, she declined to answer our specific questions about her past as a fiduciary and surrendering of her license.

Inaccessibility is something that haunts Lamborn.

“I went to see [my father] in the care home and they said, ‘Well he was in the hospital last night,’” Lamborn said. “I said, ‘Oh my God. Nobody let me know anything about him going to the hospital.’”

Lamborn said when she called Young, his conservator, to discuss her stepfather’s health, she couldn’t reach her.

“I kept calling and calling her and I couldn’t get a hold of her,” said Lamborn.

When her dad’s condition worsened, the lack of communication led to confusion over whether or not her father would receive life support, something Lamborn said he didn’t want. This wish is also reflected in a declaration signed by him in 1993 which shows if he was near death, he directed his doctor to “withhold or withdraw treatment.”

“The doctor was in the room and he said, ‘I’m going to put the breathing machine on him,’” Lamborn said. But when she told him not to, he asked if she had the authority to direct him to not do it.

“I said, ‘I don’t think so.’ So, he did,” Lamborn said.

Lamborn said after Young took over as conservator, Lamborn was unclear what power she still had and that she was led to believe, “very strongly [that] you have nothing to say about your dad now.”

But what Jamie allegedly didn’t know is that she still did have power over his health. She said this was revealed to her after her father passed when Young called her from the funeral home saying Lamborn had to be there to help with decisions as she had power of attorney for health.

When ABC10 asked Young about this, she responded with the following statement:

“This involved a Conservator case from 18 – 20 years ago. All of my accounts and reports were approved by the court. Once again, there is no factual basis for Ms. Lamborn’s accusations that a telephone call was not returned over 15 years ago. What is factual is that Jamie Lamborn held the power of attorney for her stepfather’s health care, and I was her stepfather’s Conservator. I recall talking to Ms. Lamborn numerous times regarding her stepfather’s care. There were discussions among Jamie, myself, and legal counsel as to who had the power to remove her stepfather from life support. My attorney eventually advised me that Ms. Lamborn’s power of attorney superseded my status, and thus the decision was left to Ms. Lamborn. It should be noted – For a reporter to use the accusation of a phone call not returned over 15 years ago as part of what clearly seems to be a hit piece based on this line of questioning is a rather incredulous example of your stations’ motivation to destroy an individual’s reputation.”

But Jamie said she wasn’t informed about the powers she still had over her dad.

“It made me cry. I said, ‘Why didn’t somebody tell me about that?!’” Lamborn said. “I was just so upset. So upset.”

Jamie’s father died in 2002.

Despite Jamie contesting in court, Young continued to serve as trustee of her father’s estate for the next 12 years with the documents showing the final disbursement of the trust being made in 2014.

Episode Three: 'The Old Boys' Club'

As Catherine stands over her mother’s plot at the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery, she recalls her family’s lineage.

“Our family goes back here from the 1880s… 1850s actually,” said Catherine. “So, Sacramento is a very near and dear place to my heart, and my family as well.”

But Catherine had no idea she would spend her mother’s final days fighting in one of Sacramento’s powerful institutions: our probate court.

“It was like the Wild West out there,” said Catherine. “Probate law is so complicated. It’s intrinsic, complicated and really hard to follow.”

The Sacramento County Probate Court isn’t one for the weary. Department 129 handles all probate matters in Sacramento County--everything from probates of estate, to litigation regarding trusts or wills, to administration of estates as well as conservatorships.

It’s a range of matters and they move quickly. According to Probate Court Judge Joginder Dhillon, the court sees roughly 100 cases a week.

“The typical calendar is about 25 to 30 matters every day,” said Judge Dhillon.

In 2013, one of those was Catherine’s mom, who was placed under a conservatorship.

“Basically, right after my dad died and all of a sudden I’m having to deal with court, and our family is fighting my mom being conserved,” Catherine recalled.

All conservatorships in California are appointed through each county’s probate court. They can be fast hearings for the power they provide over another individual.

“We have the right to decide where we live. We have the right to make our own medical decisions. We have the right to decide who we talk to, who we have visitors from or not if we don’t want [visitors],” Kincaid said. “When you’re put under a conservatorship, you lose that. So that’s a very serious thing to do.”

A variety of people can be appointed conservator, including relatives.

“I think the ideal circumstance is where the conservatee is requesting that somebody serve as their conservator,” said Judge Dhillon. “Or the relationship is long and there’s a demonstrated history of caring and support.”

But if family members aren’t getting along, the probate court may lean towards appointing an outside person to serve as conservator, which will be a professional fiduciary. This fiduciary is required to serve as an unbiased third-party conservator.

The California Probate Code--the rules of the probate court--says “clear and convincing” evidence is required for a conservator to be appointed. It also says the proposed conservatee must attend the hearing, but exceptions are made for a number of things, including if they’re unwilling to or medically unable.

This means that sometimes the proposed conservatee isn’t part of the decision being made on their behalf.

“In a lot of cases, the court never sees that proposed conservatee who then becomes the conservatee,” said Kincaid. “This can go on for years and the court never sees them to know what they might object to, or what their needs might be.”

That’s where the court investigator comes in.

“The probate investigator brought a real-time snapshot of what’s going on,” said Marshall, who served as a probate court investigator in Sacramento for 29 years before opening his care homes.

After a petition for a conservatorship is filed, a court investigator interviews the conservatee, informs them of their rights, then provides the judge with their final report.

“The folks that become probate investigators, we all had a sense of – not case management, but wanting first and foremost for the judge to have as balanced and concise a report of what we observed,” said Marshall.

If the conservatorship is approved, the investigator is supposed to continue to be the eyes and ears of the court.

“We go out within a year to check on them to see how things are going,” said Judge Dhillon. “Then every two years after that to make sure, again, that things are going well.”

Marshall was an investigator from 1980 to 2009. Throughout his career he said there were multiple circumstances of an increase in cases and decrease in funding of certain entities, like the Public Guardian’s office. Many of these situations led to even more responsibilities for court investigators, meaning there was less oversight.

Specifically, accountings for conservatorships of the estate were what sparked a court investigator to start their case. But if an individual was under a conservatorship of person, there was no accounting to initiate their investigation, causing some cases to go overlooked or be pushed back.

“A backlog was created,” said Marshall. “I can’t say how many people fell through the proverbial cracks there but it became a matter of 'do we have enough resources to do it all?' And the answer was no.

The “silver tsunami” is a term for the massive population of the aging baby boomer generation, and the waves are crashing down, flooding the vast majority of California probate courts.

“And [probate courts are] only going to get more [inundated],” said Kincaid. “There are a lot of us getting older.”

“If you go and sit in a probate court calendar, it’s not the judge’s fault but it might have a one hour calendar with 80 matters before him or her,” said Hackard. “So, it’s very difficult for that judge to really listen to what’s going on plus [the judge] becomes used to hearing the same story over and over again, and pretty soon it’s easy to dehumanize it.”

Specifically in Sacramento, Judge Dhillon said the amount of cases isn’t dramatically rising but calls their current caseload “high volume.”

“We do want to ensure we treat all people that come before the court respectfully but balance that with the fact that we have a calendar that requires that if we spend a lot of time on one matter, that could potentially affect how much time we spend on another,” said Dhillon.

He said within the last year, the Sacramento County Probate Court has handled roughly around 2,000 new case filings. And while he has only been on the probate bench since February, he said his 20-person probate-veteran staff helps him be prepared.

“Oftentimes much of the really hard work is done outside of the courtroom,” said Judge Dhillon. “If everything is done right, it can go actually really quickly in the courtroom.”

In the book, Guardianships and the Elderly: The Perfect Crime, author Dr. Sam Sugar wrote that significant money can be made by court insiders who know how to play the system. And our investigation found two significant ways that appear to be loopholes around court regulations and oversight.

Ex parte petitions

The first is ex parte petitions, also known as emergency petitions.

The probate code requires each party to have 15 days for evaluations from a doctor and court inspector after a petition of a conservatorship is filed. But if an emergency petition is filed, it’s a different story.

“You go in with an ex parte petition, which means in some counties you don’t have to tell anybody,” said Kincaid. “In some counties, you have to give 48 hour notice and in some counties you just do it.”

In Sacramento county, ex partes are “in the event of an emergency” and must be submitted at least 24 hours in advance of the desired hearing time. All interested parties must be notified in writing.

“You can’t just come in and say, ‘I need this today,’ or something like that,” said Judge Dhillon. “You have to say, ‘I am filing for a general conservatorship’ but because of some good cause – some medical emergency. ‘There’s a reason why we have to move this up on the calendar. I’ve given notice to all the necessary people.’ If anybody objects, they can let the court know.”

But because ex partes are “emergencies,” they can lead to a lack of oversight as court investigators are not required to do an investigation when this type of petition is filed.

Kincaid said she has seen emergency petitions throughout California help appoint conservatorships fast… and sometimes with unverified allegations.

“Like, ‘This evil brother. He’s using undue influence to get control of my father and get control of his assets. He has a history of criminal behavior, he’s a drug addict! He’s been stealing from my father for years! I have to have conservatorship right now to protect my father and his estate,’” Kincaid explained. “And the judge will probably go, ‘Wow. That’s pretty convincing.’”

It’s a similar story to what happened to Carol Kelly here in Sacramento in 2006.

According to court documents, an ex parte petition was filed by fiduciary Carolyn Young after an anonymous call was made to adult protective services saying Mary Jane Mann was at risk of abuse from one of her daughters, Carol.

This led to Mann being placed under a temporary conservatorship of Young.

“A petition was written by Young herself that contained false information,” said Kelly. “I had been entrusted with the lives of hundreds of children as a public school administrator, elementary school principal. These were wild, wild accusations that were written up to justify her taking control of my mother.”

Court documents reveal Kelly’s sister appeared to be in favor of the conservatorship and had concerns about Kelly, alleging she was isolating their mother from her.

“I never wanted to lose a sister… I never wanted it to happen but a wedge was put between us,” said Kelly. “It did not help my mother. I can’t tell you how hard it is to watch someone you love have to suffer, have their funds and their freedom taken away.”

Court records show their mother, Mann, said she was “perfectly capable of managing her own financial affairs.”

Two years after the conservatorship was appointed, Mann sued for civil rights violations. In a binding settlement and agreement that was reached with Young and her legal counsel, the conservatorship was dissolved with the agreement that Mann drop the suit, according to the settlement agreement and mutual release.

It’s one of the few cases ABC10 found where a conservatorship was abolished, but after a costly battle. Kelly estimates her mother’s estate was depleted by $100,000 at the end of the conservatorship.

Kelly believes this conservatorship was never needed, and it took an emotional and financial toll on her mother.

“My mother was totally destroyed… she would say, ‘When your freedoms are taken away, there’s no reason to live,’” said Kelly. “I have no doubt that Carolyn Young’s actions took years off my mother’s life.”

Young refused our many requests, spanning multiple months, for an on-camera interview. However, she answered some of our questions in writing. When we asked about Mann’s mental capabilities, Young responded in-part "there is no basis in fact for Carol Kelly’s 'opinion,'” and noted multiple times that she follows the direction of the court.

The trust

The second loophole around the probate court system is through the trust.

“It might be because the maker of the trust doesn’t have a close relative that they feel that they can depend upon or they don’t know someone else who can be trustee,” said Hackard. “So they interview a professional fiduciary.”

Once you petition the court to get on the trust, it’s the end of the court’s oversight.

“The trust has basically three or four parties,” said Hackard.

A trust has the maker of the trust, the trustee, who is in charge of assets and applying directions of the trust, and the beneficiary, who is supposed to benefit from assets in the trust.

It’s set up in a way where oversight is written in.

“And because you have that, it doesn’t have to go through a probate court,” said Hackard. “Sometimes they end up going through a probate court and oftentimes they don’t. It’s an advantage to timing and costs.”

While avoiding court can help avoid expensive legal fees, it can be detrimental if the trustee doesn’t execute the trust in the way the maker of it wanted.

Specifically, here in Sacramento, Marshall saw how using the trust changed the conservatorship business.

“That’s a big factor in how the legal community moved away from court oversight that was inherent in the conservatorship process,” said Marshall.

He believes a combination of resources tightening within the Public Guardian’s office, the initial entity that was appointed to oversee conservatorships. Plus, going around the court with trusts was how the conservatorship business evolved from public to private, Marshall said.

“The legal community recognized that the amount of legal work and having their fees and the fees of their private fiduciary clients had to be approved by the court,” said Marshall. “Some judges, frankly, were not pleased with the charges. The court had full authority to reduce/eliminate anything they wanted to and that wrangled a lot of folks in the legal community and fiduciary. So, a workaround is if the trust is set up in such a way that there’s no (court) review, then you can charge what fees you want and if it’s not reviewed, then you get your fees automatically.”

In the eighties, Marshall said there was a mass exit of a group of professionals from the Sacramento County probate court to the private side.

“Carolyn Young was at the Public Guardian’s office,” said Marshall. “She was one of the first private fiduciaries I had ever heard of.”

This group-exit was something Carole Herman, founder of the Foundation Aiding the Elderly, saw too.

“They left the county because, to me, I think they knew that there was a money opportunity and to start their own business,” said Herman, “and they could see that.”

And it was the start of a successful business for Young.

“I think she’s the leading licensed fiduciary in Sacramento,” Hackard noted.

Through a public records request, ABC10 acquired Young’s annual statements from the California Professional Fiduciary Bureau.

In her 2020 statement Carolyn Young reported managing $111,472,265.81.

The other fiduciaries in her business are her two children, Zach Young and Lindsay Bowman.

In his 2020 statement, Zach reported managing $135,000,000. Lindsay reported $30,513,047.38.

Altogether, that’s nearly $277,000,000 of other people’s assets Carolyn, Zach and Lindsay of the Young Fiduciary Business manage.

And fiduciaries in California handle a lot of money.

In comparison, according to the fiduciary Deborah Dolch’s 2017 annual statement, she reported handling $158,855,659.

According to the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, around $13 billion of other people’s assets are managed by fiduciaries in California.

In a statement to us, Young said, “In 35 years as a Professional Fiduciary I have handled over 1,000 cases involving several thousand reports to the Court for review of my actions. In no case has the Court, or the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, ever found that I have breached my fiduciary duties.

That there may be individuals who have been displeased or even enraged with my actions on behalf of my client is, unfortunately, part of the job of the Fiduciary. On many occasions I have had to prevent a relative from (essentially) stealing from the client’s estate, and from actions that would constitute elder abuse. For this I received death threats and hopes for my eternal damnation.

In point of fact, most of my cases prove the old adage… ‘You never really know someone until you share an inheritance with them.’”

We combed through those probate court cases and we found a pattern: many of the same attorneys working with Young.

The Continuing Education of the Bar’s California Conservatorship Practice names “conflict of interest” as a factor to consider before a conservatorship is put into place. It says, “because of the appearance of impropriety, most courts will not appoint an attorney to serve as counsel for a proposed conservatee if the attorney represents the proposed conservator in other cases.”

Specifically, from January 2010 to September 2020, we discovered 56 out of 84 cases where a number of the same attorneys represented Young.

In 44 of those cases, Young was represented by an attorney named Tosh Yamamoto. In the other 12 cases, she was represented by attorneys Leland Ellison, Judy Carver, Todd Robie and Barbara Bender.

We found three out of the 56 cases where these same attorneys who represented Young then represented the conservatee in other cases where Young was petitioning to be conservator.

“There was such a dichotomy of all the players,” Catherine said. “You later find out all kinds of things of how intertwined it is.”

Young provided ABC10 with the following statement:

“At present, CMY Fiduciary Services works with over 40 probate estate planning attorneys. Most of their business is trust administration. Many of the attorneys are not interested in handling conservatorships due to their complexity and legal requirements, and they oftentimes become litigious. In addition, the majority of our business is trust and estate administration.”

Many family members involved in these cases we spoke with believe when the same attorney represents conservators, conservatees and even different family members in multiple cases, it’s a conflict of interest.

It was also part of the reason behind Lamborn suing and settling with her former attorney, Yamamoto, because she said he didn’t disclose his and Young’s previous relationship prior to Young being appointed trustee and conservator of her father.

“I was suing him because he deserved it,” said Lamborn. “I also put in a claim with the State Bar.”

The California State Bar launched an investigation into Yamamoto that was later dropped, saying Yamamoto verbally disclosed his relationship with Young to Lamborn – despite rules requiring written disclosure.

When we showed our findings of the same attorneys working with the same fiduciary to the State Bar and asked if it qualified as a conflict of interest, they refused to comment on “hypothetical” situations and recommended we seek an outside expert. So, we went to Professor Melissa Brown, who specializes in elder law and is the Director of Legal Clinics at McGeorge School of Law.

“Sacramento really is a small legal community,” said Brown.

And conservatorship law is complex, making it a smaller number of attorneys who specialize in it, Brown explained.

“So, with the probate court, it’s likely you’ll see many of the same attorneys day after day, handling the same types of cases,” Brown said.

She said attorneys cannot represent multiple parties in the same case.

“That’s a clear conflict of interest. You can’t do that. But because again, it’s a small community, if you’ve finished one case with a fiduciary and a family, or the court appoints you in another case to represent the proposed conservatee… because the court will also go through their investigative process and say, ‘Hey I think this proposed conservatee needs a lawyer,’” said Brown. “So, if the lawyer who previously represented the fiduciary or petitioner in another matter, now appears in another matter… I don’t think that’s a conflict.”

Brown also noted it’s the attorney’s moral decision of whether they should, and whether they feel comfortable taking on the case and acting unbiased in the client’s best interest.

The small number of attorneys who specialize in this field in Sacramento is something ABC10 witnessed first-hand. Months after we interviewed attorney Mike Hackard, he began actively investigating a case against Young.

During our interview, we asked him if Young has a reputation in the legal community.

“Well the reputation is, generally, if she is--or members of her family are--the conservator you can pretty well guess who the attorneys are going to be,” said Hackard. “That’s a natural thing, over the years, utilizing the same counsel. At times, the probate court is an old boys', old girls' club.”

“To find an attorney in Sacramento that doesn’t have a conflict with Todd Robie or Carolyn Young or Tosh Yamamoto is impossible,” said Catherine.

She said she went to 10 different attorneys for help, most said it was a conflict of interest and others wouldn’t take it on because it was too complicated.

It’s a similar sentiment we’ve heard from multiple sources ABC10 interviewed, including Lamborn.

“I couldn’t find any help,” said Lamborn. “I was just down to the bottom of the barrel.”

Many ABC10 spoke with lost faith in our judicial system because of the struggles they’ve encountered in trying to seek what they believe is justice.

“There is no oversight or accountability,” said Kelly. “That’s what’s really sad.”

“They know it’s wrong and they still do it anyhow… and they’re still being paid,” said Catherine. “That’s the problem. Look at the motivation.”

ABC10 reached out multiple times requesting interviews with attorneys who were referenced throughout our investigation, including Todd Robie and Tosh Yamamoto.

Todd Robie responded asking for written questions.

We sent questions to all attorneys. They didn’t respond.

Episode Four: ‘The Fight for Accountability’

“My father passed away in 2015 from pancreatic cancer,” said Gabe Meyers. “When he passed away, he left his estate and he put it into a trust. A family trust.”

Gabe is the only beneficiary--the person who inherits the trust’s assets--of his father’s trust.

Because of this, he enlisted the help of a family friend to serve as trustee--the person who helps disperse the trust how the maker of the trust, Gabe’s dad, intended. But when life got busy for that trustee, they and Gabe decided to find a new trustee and began interviewing fiduciaries.

Fiduciaries do several things. California law says professional fiduciaries can act as trustee, hold power of attorney for health and finances, and can serve as conservator.

Overall, a fiduciary’s job is to serve as a third party and work on behalf of their client’s best interest.

“That’s when we found Dawn Akel,” said Meyers. “We just didn’t want to hand the trust to anybody.”

Meyers said a major reason he chose Akel to be his fiduciary was because she sat on the Professional Fiduciary Bureau’s Advisory Committee. The advisory committee is a collection of individuals that bring knowledge to the bureau, to advise and provide guidance for the bureau – it’s a position appointed by the California governor.

“So, we felt it was pretty credible,” said Meyers.

The Professional Fiduciary Bureau was created in 2007 in legislation that was sparked after the Los Angeles Times investigated and exposed multiple serious abuses by conservators.

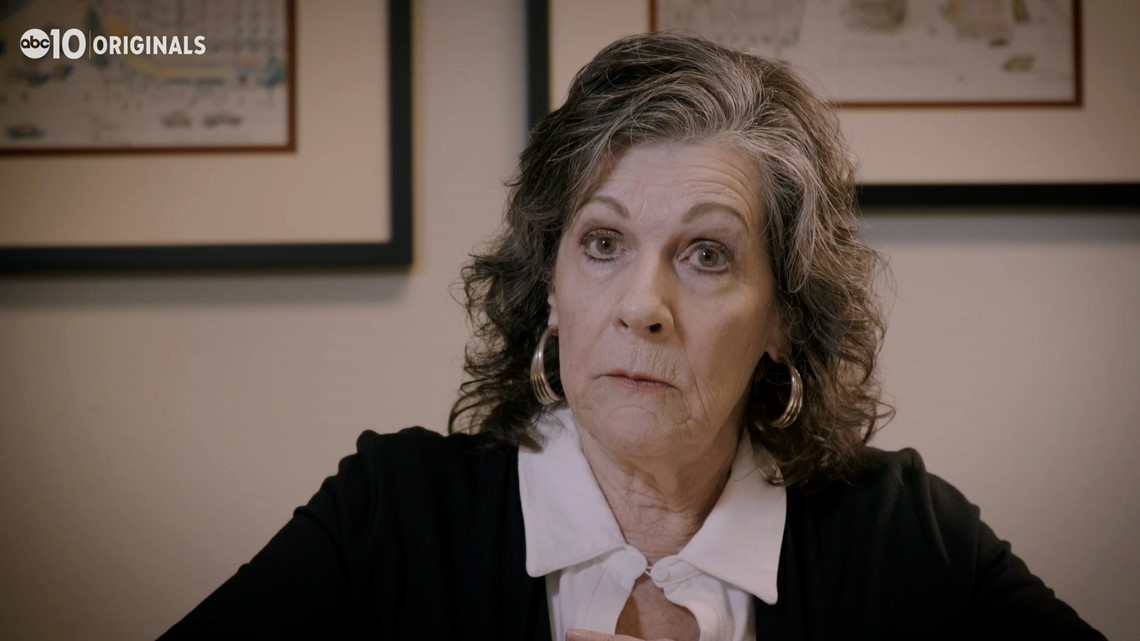

“It’s a huge nationwide problem,” said Carole Herman.

Abuse by fiduciaries, particularly conservators, is something Herman has been tracking. She’s the founder of the national non-profit corporation, Foundation Aiding the Elderly.

“This has been going on for years,” said Herman.

That’s why she was all for the creation of the Professional Fiduciary Bureau.

“I was instrumental in getting the Fiduciary Bureau established in California after I worked with the Los Angeles Times on a story about conservatorships and the dangers of conservatorships,” said Herman. “I testified at the Legislature with my experience and why I felt that there was a need for it.”

According to the Professional Fiduciaries Act, the bureau was created “to regulate non-family member professional fiduciaries.”

And professional fiduciaries handle a lot of other people’s money and assets.

The bureau lists each licensed fiduciary and how much money they oversee. We went through the bureau’s online records and added it up. It totaled almost $13 billion, specifically $12,908,486,863, of other people’s assets fiduciaries handle.

That’s just in California… and it’s far more.

That’s because the bureau’s computers can’t tally more than a penny under $100,000,000. If you go through the online records, fiduciaries that handle a huge amount of money are listed as handling $99,999,999.99. When ABC10 requested annual statements submitted to the bureau via paper, we found some fiduciaries handle millions more than that $99 million.

While the bureau tracks the money fiduciaries handle, albeit on paper, they don’t keep tallies on the number of clients they have under their care.

“I would want to know how many people rather than how much money,” said Richard Calhoun, Co-founder of Coalition of Elder & Disability Rights. “This is the issue of their putting dollars above human beings.”

The Professional Fiduciary Bureau told ABC10 they capture client caseloads by licensees having to report their “annual statements as part of the renewal process.” When we asked if there was any limitation to the number of clients or money a professional fiduciary can manage, they said California state law “doesn’t limit the number of estates or persons” a fiduciary can manage.

It’s a lot of money and power. The establishment of the bureau was intended to create oversight.

“I thought, ‘This is great. There’s an agency within the government when you have a problem, you can file a complaint and let them go in – let the investigators go in and investigate these conservatorship cases to see what’s really going on here,” said Herman. “Well, it didn’t happen.”

Herman believes she was the first person in the state of California to file an official complaint to the bureau. The 118-page complaint detailed extensive court documents, doctor’s evaluations and attorney correspondence and was against fiduciary Carolyn Young, in regard to Mary Jane Mann.

“[The complaint] was a lot of work,” said Herman. “And nobody did anything about it.”

Herman said she never received any written response to her complaint. She said on October 18, 2011, two and a half years after she filed the complaint, she got a phone call from the bureau saying they had closed it.

While the bureau said every complaint filed gets an “acknowledgement letter” after 10 days, long wait times for resolutions is something we’ve heard over and over again from multiple people we’ve spoken with through our investigation, including Julie Doherty.

“I have filed a complaint [with] the California Professional Fiduciary Bureau,” Doherty told us in our interview in September 2020. It’s now May 2021 and Doherty said she still has yet to receive a decision or overall response.

According to the notes from the Professional Fiduciary Bureau meetings, the bureau receives around 135 complaints each year. In a statement to ABC10 they said they “investigate every complaint.”

But our investigation found the reason behind the delay in response to complaints. We requested a full list of every employee that works for the Professional Fiduciary Bureau. In response, we got a list of three; one being the person who does investigations, Sue Lo.

This means the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, the only state agency overseeing fiduciaries, has only one person to investigate hundreds of detailed complaints.

The bureau’s spokesperson, Matt Woodcheke, told us that the bureau is “funded solely through licensing fees” and that’s why they currently employ “one enforcement analyst to conduct investigations.”

While addressing the bureau in their January 10, 2019 meeting, Calhoun addressed a lack of oversight.

“For three years there were 408 complaints filed by the public. Exactly zero complaints resulted in any disciplinary action,” Calhoun said. “I’m sorry, I don’t buy those numbers. You do not get 408 complaints from the public, and not one be a violation.”

Calhoun and Kincaid co-founded the Coalition for Elder and Disability Rights, an advocacy group focused on the California conservatorship industry, after Kincaid’s mother was placed under a conservatorship in 2010. Kincaid said it was physically and financially abusive.

“[My mother] was skin and bones. We found out in litigation that she wasn’t getting fed,” Kincaid said. “You can’t mentally process something like this can happen.”

They’re worried nothing will change.

“That’s my motivation. I am a perfect target,” said Calhoun. “If I don’t change the system, I’ll be a victim… I’d rather kill myself than be a future target the way the system is now.”

Since the organization’s start in 2014, they’ve monitored case after case of conservatorships in California. One of their biggest concerns is lack of oversight by the Professional Fiduciary Bureau, especially regarding complaints.

“In one case a fiduciary actually killed her client. She withheld food and hydration and he died. The court ordered her to restore food and hydration and she did after three days, but that was too long and he died,” said Kincaid. “I turned that in to the Professional Fiduciary Bureau – every single one of those cases, they found no violation of the license.”

That Professional Fiduciary Bureau says they don’t do these type of investigations because they’re a licensing agency.

The bureau responded to ABC10’s questions saying they “are not a law enforcement agency” and do not “have the authority, by law, to conduct criminal investigations.”

It’s a sentiment that’s heard over and over again during the bureau’s meetings, coming directly from Chief Rebecca May.

“Law enforcement believes that once you’re conserved, you’re no longer entitled to law enforcement protection,” said Calhoun. “Law enforcement says, ‘Oh that goes to adult protective services, which is social workers.’ So, you end up with less protection now that you turn 65.”

This means that when abuse happens in a conservatorship, the Professional Fiduciary Bureau will direct those concerned about the abuse to law enforcement – and law enforcement directs them to adult protective services.

This is shown in a response Kincaid got from the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office that she shared with ABC10 which said, “All of the information you provided has been forwarded to the Santa Barbara County Department of Social Services – Adult Protective Services, which is the county agency that is responsible for investigating these types of complaints.”

“And it gets even more nuanced than that because most of the conservatees are in (caregiving) facilities and adult protective services only provides service for people in the community,” said Calhoun. “So, they don’t even provide services in the facilities.”

This despite the Professional Fiduciary Bureau being created to “regulate professional fiduciaries” as well as their code of ethics saying, “the protection of the public shall be the highest priority for the bureau.”

Additionally, the California Code of Regulations states that fiduciary licensees must “comply with all local, state, and federal laws, regulations and requirements.”

“It’s okay to kill your client. That’s not a violation of your license,” said Kincaid. “The only thing they’re issuing citations on are, ‘You didn’t submit your paperwork on time, you didn’t pay your licensing fee on time.’ Now that’ll get you a citation.”

The bureau’s website shows there are a few cases where licensees have had their licenses revoked, suspended or surrendered.

“That happens after some other court finds a problem, does an investigation, goes through whatever months/years are required for the courts to grind through those cases,” said Kincaid.