SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office exerted control over a powerful state agency that is supposed to operate independently, “micromanaging” decisions big and small at the California Public Utilities Commission according to its former executive director.

“We do whatever the governor tells us to do, period,” former CPUC executive director Alice Stebbins said. “You don't do anything without [Gov. Newsom’s] staff reviewing it or talking to you or approving it. And that's the way it was.”

Internal CPUC documents obtained by ABC10 reveal the agency took direction from Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office and even submitted its work to the governor’s staff for multiple levels of “approval.”

The records show that on at least one occasion, the need to secure approval from Newsom’s office delayed CPUC business for a matter of days, frustrating the agency’s employees.

The documents were obtained as part of ABC10’s FIRE - POWER - MONEY investigation, which will examine how the state government under Gov. Newsom responded to PG&E’s crimes by offering the company financial protection.

The evidence of the governor’s office inserting itself into relatively small details of the CPUC’s business raises questions about how much control the governor exerted on bigger issues, like the PG&E crisis.

Article XII of California’s constitution makes it clear that the CPUC, which sets tens of billions of dollars in rates paid by California utility customers, does not serve at the pleasure of the governor.

“It’s absolutely in violation of the state constitution,” said Mike Aguirre, a former San Diego city attorney who has repeatedly opposed the CPUC. “Would you want judges before they make their decisions to run it by the governor’s office to see if it was okay?”

Gov. Newsom does not have the authority to fire CPUC commissioners. That can only be done by a two-thirds vote of both chambers of the legislature, a higher standard than it takes to impeach a judge.

Stebbins said that under Newsom, the governor’s office insisted on being in charge of CPUC business, “especially anything with PG&E, anything with the bankruptcy.”

After PG&E committed the felony manslaughter of 84 people by starting the 2018 Camp Fire through criminally reckless operation of its power grid, the CPUC played a key role in approving PG&E’s plan to exit bankruptcy and waived a $200 million fine for PG&E’s safety violations.

In previous interviews Stebbins apologized for her role in facilitating those decisions, which were made by the CPUC’s five voting commissioners.

Gov. Newsom and CPUC President Marybel Batjer both declined repeated requests to be interviewed. ABC10 sent both a detailed list of written questions.

Batjer did not respond at all. Newsom’s response ignored every question related to the independence of the CPUC.

“It’s not just that it’s unethical. It’s not just that it’s not honest. It’s that it is cumbersome and just doesn’t produce good policy,” Aguirre said.

‘USUALLY WE ARE COORDINATING WITH THE GOVERNOR’S OFFICE’

As the COVID-19 pandemic began disrupting life on a grand scale in March 2020, the CPUC wanted to do something simple: send a letter to companies it regulates.

It took four days.

The letter was unremarkable; designed to give a “push” to “bad-acting” internet and mobile phone companies.

What is remarkable is the process the CPUC had to go through to get permission to send the letter out.

“It slowed things down,” Stebbins said.

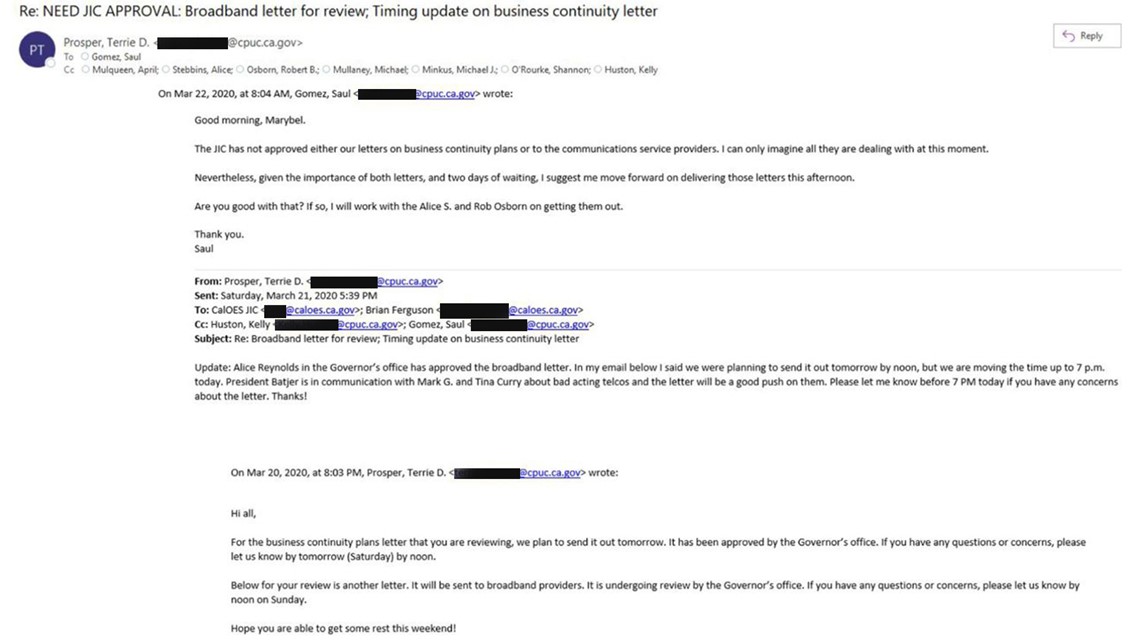

After they finished writing the letter on a Friday, CPUC officials worked through the weekend trying to obtain two different levels of approval for the letter from Gov. Newsom’s staff.

“Alice Reynolds in the Governor’s office has approved the broadband letter,” CPUC spokesperson Terrie Prosper wrote in an email that Saturday evening.

Prosper’s email was directed to a group of more Newsom staffers at the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) asking for them to reply that night if they had “any concerns about the letter.”

By the next morning, the approval from Cal OES had not come. It was holding up the broadband letter and another the CPUC wanted to send.

“[Cal OES] has not approved either [of] our letters,” deputy CPUC director Saul Gomez wrote on Sunday morning in an email directed to Batjer. “Given the importance of both letters, and two days of waiting, I suggest [we] move forward on delivering those letters this afternoon.”

When Batjer replied two hours later, she didn’t give permission to send the letter.

“This is not good,” Batjer wrote in response. “We need to get the letters out!”

Batjer promised to reach out to the top staff at Cal OES herself to check on the delay.

The emails do not reveal whether Cal OES finally gave its approval, but that afternoon Prosper suggested it might be okay to send the letter anyway since Cal OES didn’t respond by the deadline she set.

“Usually we are coordinating with the Governor’s office before we send something to [Cal OES] and it’s helpful to let them know if the Governor’s office has already approved,” Prosper replied on Sunday afternoon, pointing out that she had given a deadline for Cal OES to respond the night before.

Cal OES did not respond to emails asking why it believed it had the authority to approve the work of an independent agency.

Batjer gave a “green light” to the letter on Sunday afternoon. The letter finally went out on Monday.

Aguirre, who frequently argues that the CPUC is corrupted by improper political influence, was surprised to see such low-level “micromanaging” of the agency by Gov. Newsom’s staff.

“It’s really kind of silly,” Aguirre said. “Do you mind if we ask the telephone monopolies if they might be providing protection for folks suffering from COVID?”

‘COMPLETE CONTROL’

Stebbins, who is in the middle of a legal battle alleging wrongful termination by the CPUC, says Gov. Newsom’s office went further than making the CPUC get approval when it came to some of the agency's most important decisions.

“When it came to PG&E,” Stebbins said. “It was a different kind of involvement. It wasn't the same. It was more of a direction.”

The agency refused to release messages between Batjer and key staffers at the governor’s office. ABC10 has pursued legal action trying to compel the agency to release those records.

Stebbins was hired to manage the CPUC toward the end of Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration and witnessed a shift after Gov. Newsom took office.

“Before there was more independence,” Stebbins said. “We weren't used to having to have a lot of our press releases or information reviewed.”

CPUC emails obtained by ABC10 show the agency’s officials did get press releases “approved” before sending out news to the public.

“At first I thought maybe it's because this is a new governor. He just kind of wants to get his feet wet,” Stebbins said. “But I think it was really a control. It was just being in complete control.”

FIRE - POWER - MONEY

WATCH MORE FIRE - POWER - MONEY: