FOLSOM, Calif. — Folsom faces challenges converting many city vehicles to zero-emission vehicles in accordance with California state law.

In September 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered all new light-duty vehicles, including passenger vehicles and half-ton pickups, sold in the state to be zero-emission by 2035 in an effort to reduce demand for fossil fuels.

Where feasible, off-road vehicles and equipment operated in the state must be zero-emission by 2035. Medium and heavy duty vehicles, including three-quarter-ton pickups and larger, must be zero-emission when feasible by 2045.

Folsom’s vehicle fleet, excluding the Folsom Fire Department, consists of 447 vehicles, trailers and pieces of equipment, according to city documents. Regulations relating to Newsom's order will directly affect the life cycle cost of roughly 250 of Folsom's existing fleet.

Mark Rackovan, the city’s public works director, said in a presentation to Folsom City Council on Feb. 27 there are about 170 vehicles in the fleet subject to zero-emission transition.

Zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) include battery electric vehicles, plug-in electric vehicles and fuel cell electric vehicles. Hybrids are not ZEVs.

“It will not be things like ladder trucks or ambulances...,” Rackovan said to council during the meeting. “You're going to see this primarily in pool vehicles, light-duty pickups and then the heavy duty maintenance vehicles you see us using on a daily basis.”

Rackovan noted during his roughly 45-minute presentation that vehicles excluded from ZEV conversion include military tactical vehicles and snow removal vehicles.

“I am considering whether to put a 50-caliber gun emplacement and/or a snow plow on all of our vehicles to help us with the exemption,” Rackovan joked, as his tidbits were met with laughter from council members. “I’m kidding. Some of our vehicles probably qualify as historical vehicles; they go back to about 2006 or so.”

What conversion challenges is Folsom facing?

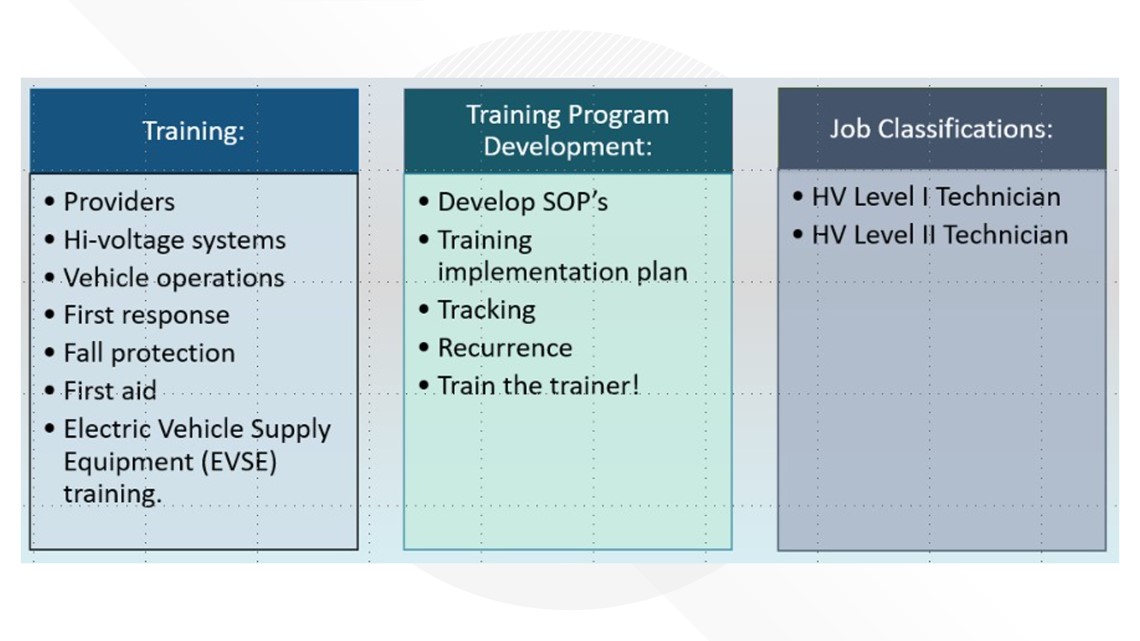

A major challenge facing Folsom’s ZEV conversion is training new and existing employees on ZEV operations, high-voltage systems and first aid, Rackovan said.

The city also has to develop new standard operating procedures, train people on how to implement those procedures and, when hiring, create new job descriptions and requirements for future hires, he said.

“Are there people out there in the industry that are prepared to do essentially high voltage electric vehicle repair? If the industry is keeping up, then maybe we’re in good shape,” Rackovan said. “But, I think there’s going to be a little bit of lag. I think during this transition period, we are going to see some service delivery issues trying to get our vehicles repaired.”

Rackovan expressed concerns about upfitting electric vehicles.

He wondered if any electric vehicle could be outfitted with a light bar and other attachments that Folsom staff generally adds to city vehicles once Folsom obtains them.

“It’s one thing to be able to obtain an electric version of a heavy duty pickup truck,” he said. “Where do you drill into the vehicle to add these new elements without damaging the electrical system?”

Damage to an EV battery module may not develop into a fire for days or weeks, Rackovan said in his presentation.

“There is not enough evidence to know yet if electric battery fires can occur more commonly than…a gas-powered vehicle, but the consequences of these are significant because some of these happen after the fact,” he said.

Rackovan listed the following operational questions the city would have to consider:

- Regarding take-home trucks, commute mileage uses up battery range. Will employees be expected to charge at home?

- Will the city assume the risk of an EV fire damaging an employee’s home?

- In terms of charging session interruptions, is someone notified of power interruptions?

- Are staff on hand to restart charging stations?

- Does the charging station or vehicle restart sessions automatically when electrical power is restored?

- Does the city have a back-up plan for three days of power outages?

- Does the city have alternative locations with unaffected electrical grids to charge vehicles?

Additional challenges

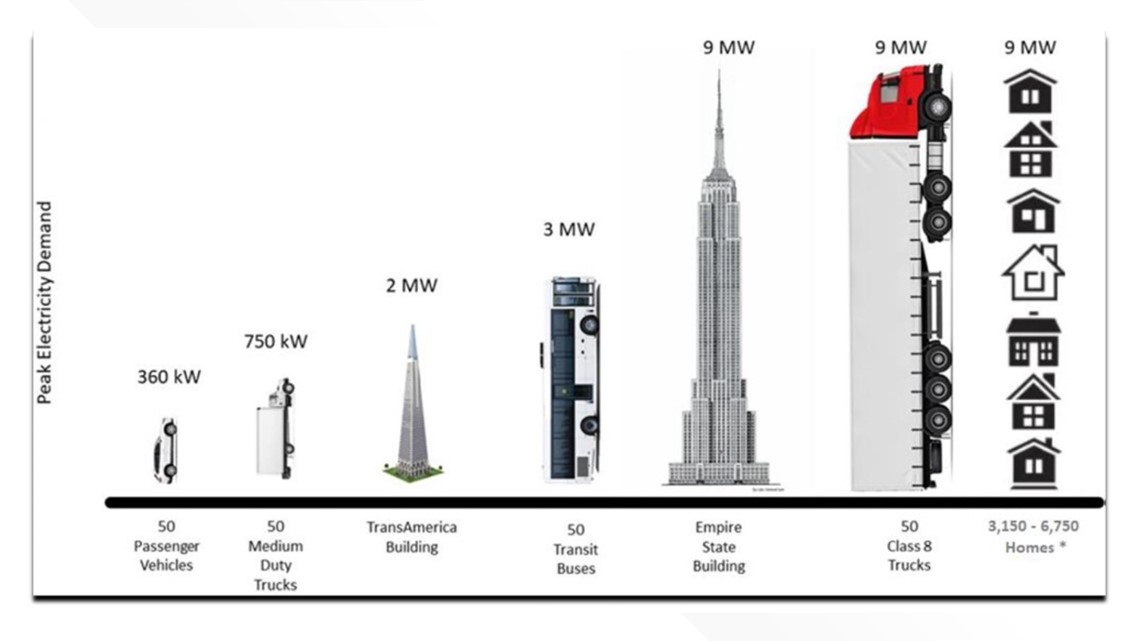

In order to provide the council with a perspective on electricity requirements in the years to come, Rackovan presented a graph displaying a semitruck next to the Empire State Building.

A Class 8 truck generally weighs over 33,000 pounds, which is roughly the size of a garbage truck.

“Fifty class 8 trucks is essentially the size of our waste collection fleet,” he said. “If we go with a ZEV garbage truck fleet, that’s the equivalent of powering the Empire State Building for one night or about 3,100 to 6,700 homes — about the size of Folsom Ranch. And, we have about three times that many vehicles that are going to need to be powered.”

Rackovan also said the city’s maintenance facility is not large enough to fulfill Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requirements as it currently stands.

“OSHA requires a 10–foot clear bubble around an electric vehicle that is in for maintenance, so that means nothing metal — nothing that can cause arcing — within a 10-foot radius, 360 degrees around the vehicle,” he said.

Arcing is electric discharge with a high density.

The exact ZEV conversion cost is unknown, but Rackovan maintained it would cost millions of dollars even with grant funding.

Fleet managers estimate truck replacements subject to transition will cost 1.5-5x higher than their internal combustion engine counterparts’ historical cost, according to city documents.

“Another challenge in determining the ongoing cost of electric vehicles is the lack of historical data to use for determining life cycle cost,” city documents read.

ZEV trucks can cost anywhere from $90,000 to $1 million, according to the city. Limited cost data is available. Charging infrastructure costs $35,000 to $200,000 per charger depending on voltage and amperage needs.