If you're viewing this on the ABC10 App, tap here for multimedia.

More than three decades after an act of Congress slashed funding for community clinics, homeless mentally ill are still the subject of concern and debate in California communities.

Police encounters with mentally ill people have also ended in tragedy, as in the case of Joseph Mann in 2016, who was gunned down by Sacramento police officers.

California’s history of dealing with mental illness mirrors the nation’s in its arc of moving from care in institutional settings to more community-based efforts.

In the Victorian era, grand institutions in rural settings were fashionable, as country air and fresh produce were thought conducive to healing wounded psyches, as were the large, grand buildings themselves, according to the book, "The Architecture of Madness" by Carla Yanni.

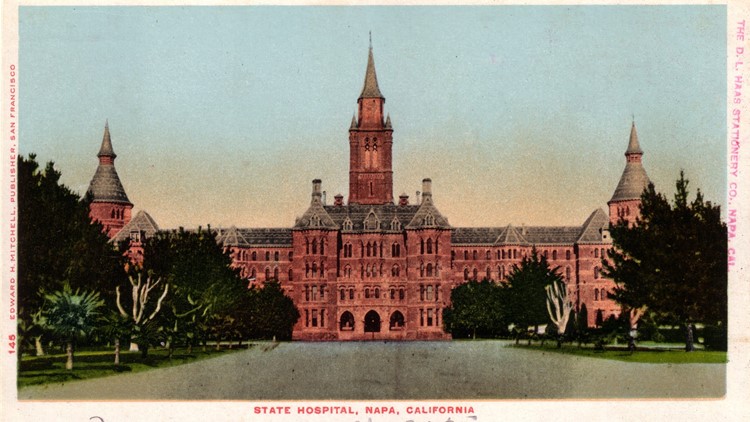

Napa State Hospital, California’s first dedicated asylum, followed the Victorian model with a striking, turreted Gothic structure nicknamed ‘The Castle.’

The four-story, 500-bed facility was built when Stockton State Hospital became overcrowded, opening its doors Nov. 15, 1875, according to the Department of State Hospitals. Then known as Napa State Asylum, the hospital was self-sufficient, raising poultry, vegetables, dairy cows, orchards and other crops on its original 192 acres.

But over the years, many of these large hospitals became overcrowded and some fell into disrepair. Institutional treatment became associated with neglect and abuse of patients, as described on the Psychiatric Times website. Napa Hospital was not immune to these ills, with overcrowding well documented.

By 1891, the facility built to house about 600, held a population of 1,373, according to a Napa County Historical Society timeline. Overcrowding continued to be a problem. In the 1920s, cottages meant to accommodate 26 people were packed with almost three times that.

The formative years of the modern psychiatric profession were a time of experimentation, with extreme therapies and practices, including lobotomy, straight jackets and padded cells, hydrotherapy, and the ever-controversial electroconvulsive therapy.

In California, reforms included the Short-Doyle Act in 1957, which provided a funding mechanism for community mental health services. In 1968, The Lanterman-Prentis-Short Act required a judge to sign off on the commitments of patients, bringing a more uniform approach to commitments and significantly reducing the number of commitments.

The reforms and the push for a community-based strategy largely hinged on drug therapy, as doctors believed the drugs like Thorazine would calm people with mental illness enough so they could function in society – along with treatment at outpatient clinics in their communities.

The trend of reduced populations continued throughout the 1960's and 70's. On June 30, 1972, more than 3,800 patients were released from Agnews State Hospital into the San Jose area, creating a "mental health ghetto," as service providers scrambled to convert vacant buildings into board and care homes, according to NAMI of California.

The steady release of patients into communities created urgency for the creation of more community-based services for the treatment of mental illness. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the Mental Health Systems Act to provide community block grant funding to states for such services. However, when President Ronald Reagan went into office the following year, he signed the Omnibus Budge Reconciliation Act of 1981, retracting the funding, according to GovTrac website.

Some argue that the whole concept of "community-based care" was misguided, or even fatally flawed, and the doctors who testified for the President’s Commission on Mental Health over-hyped its potential and over-relied on the ability of tranquilizing drugs like Thorazine to treat mental illness. In the absence of funding for the proposed mental health centers, it would be difficult to say what could have been.

California state hospitals now serve mainly patients committed through civil and, mostly, criminal court action, according to the department's 2017 annual report.

Last year, about 91 percent of the 13,000 patients treated by Department of State Hospitals were being held relating to criminal cases; in dispositions including not guilty by reason of insanity, incompetent to stand trial, sexually violent predator and mentally disordered offender designations, according to the 2017 report.

The population was 87 percent male; 42 percent white, 25 percent black and 25 percent Latino; 79 percent were high school dropouts, with only one percent claiming “some college.” About half of the patients are over 41, with 40 percent diagnosed as schizophrenic – the largest diagnosis category. Schizoaffective disorders, which include mood disorders like mania or depression, accounted for 24 percent; 16 percent paraphilia, a diagnosis of "abnormal" sexual desires; and 20 percent "other" make up the balance, according to the report.

About half the patients in the DSH system come from Southern California, 20 percent from the Bay Area, 14 percent from the Central Region, and 11 percent from the North Central Region.

Since deinstitutionalization and the subsequent funding cuts, California has worked to replace funding for community mental health services, passing Proposition 63, the Mental Health Services Act, in 2004. The MHSA imposes a one percent tax on personal income above $1 million, with the revenues used for prevention, early intervention, service needs and ancillary support.

However, services for those with mental illness continue to vary from county to county, mainly based on the county's ability to fund services, said Jessica Cruz, executive director of NAMI California. Access to a uniform standard of mental health services regardless of county is one of the reforms NAMI works toward.

Almost four decades since funding for community centers was cut from the budget, many people with mental illness and their families continue to struggle to get the treatment and assistance they need — which might prevent a collision course with law enforcement.

A timeline of mental health care in California: