SACRAMENTO, Calif. — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

It’d be just another normal day, nearly 17 feet above Highway 101 in Agoura Hills.

A southern alligator lizard and a western toad hide from the heat in the greenery of restored native vegetation. Mountain lion cubs pounce on rocks and spring into the nearby canyons. The sun glints on the feathers of a golden eagle soaring overhead.

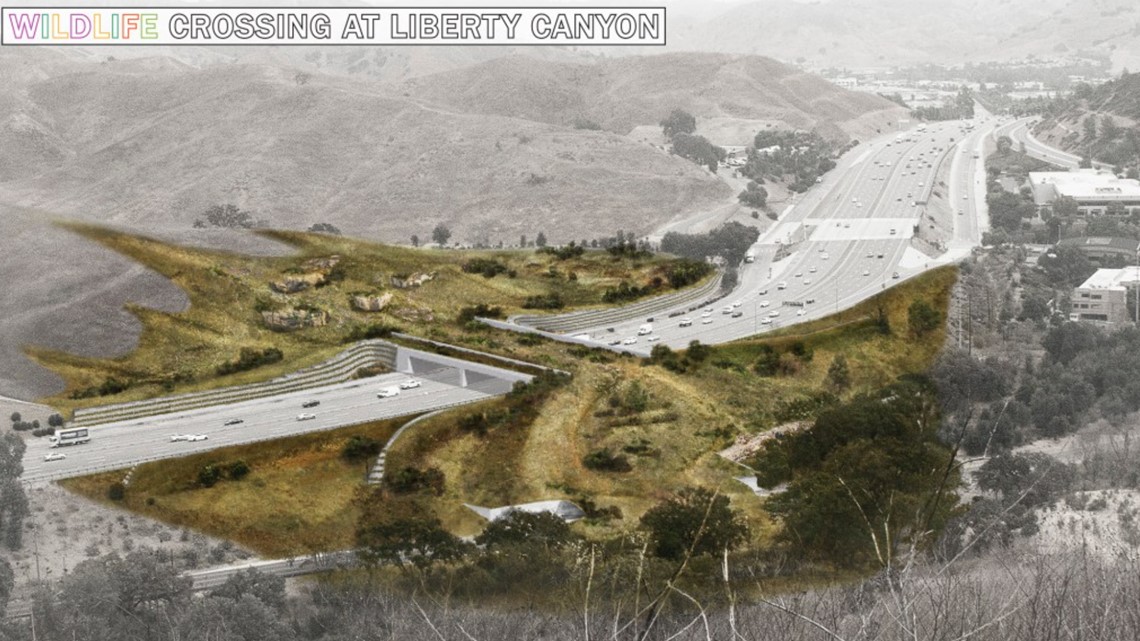

This is the scene environmentalists hope will someday become reality on a massive overpass above the ten-lane freeway that cuts through the Santa Monica Mountains near Los Angeles. The project known as the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing is one step closer to happening now that Gov. Gavin Newsom has signed a budget that includes $7 million to help build it — and another $54.5 million for similar projects in other parts of the state.

It’s part of a larger nationwide push to build special bridges and tunnels that help animals safely cross busy roads and freeways. The goal is two-fold: to give species at risk the space they need to find mates, and to reduce the number of car crashes that imperil both wildlife and humans.

About 7,000 vehicle crashes a year on California highways involve large wildlife, such as deer, according to 2018 data from the Road Ecology Center at the University of California, Davis. That’s nearly 20 crashes a day, at least. Many are likely unreported.

And they aren’t cheap — for the drivers or the government. Between 2015 and 2018, wildlife crashes have cost more than $1 billion. The expenses include car damage, personal injuries, emergency response, traffic impacts, lost work and the clean-up.

Highways aren’t just crash sites for the deer caught in the headlights; they’re also a great divide that can threaten the future of an entire species.

That’s because highways cut through critical habitat, making it impossible for animals from one side to breed with animals on the other. This leads to inbreeding and deformities that result from dwindling genetic diversity.

Wildlife crossings can help.

Utah saw a 98.5% reduction in deer mortalities when it built two animal underpasses on a stretch of highway that blocked traditional migratory routes. In Colorado, wildlife-vehicle collisions dropped by 89% after the state built two bridges to help mule deer and elk safely cross a highway. Arizona, Florida, Montana, Oregon, New Mexico, Washington and Wyoming have also built successful wildlife crossings.

But California? Despite its environmentally-aware reputation, the Golden State lags in building these crossings. The Liberty Canyon overpass would be California’s first bridge on the state highway system designed specifically for fostering wildlife connectivity. And even with the new funding, it’s still years away from completion.

“We’re not an environmental state,” said Fraser Shilling, co-director of the Road Ecology Center at UC Davis. “We don’t have environmental-based legislation that is resulting in protection of wildlife.”

This year, however, conservationists are encouraged by action at the state Capitol. A bill making its way through the Legislature would encourage the state transportation agency to build more wildlife crossings.

And the budget lawmakers passed last month includes new funding to build animal overpasses and underpasses. In addition to the $7 million for the bridge at Liberty Canyon, it also includes $2 million to build a tunnel for deer and mountain lions to pass under Highway 17 in the Santa Cruz Mountains, plus $52.5 million for other wildlife crossings that have yet to be identified.

Wildlife crossings have gained support across the political spectrum — both from environmentalists as well as groups that advocate for hunters. Even though he disagrees with California’s ban on hunting mountain lions, Dan Whisenhunt, chief executive officer at the California Deer Association, supports building more overpasses and underpasses.

“This is one time that politics is listening to common sense… because nobody loses in this,” Whisenhunt said. “It could be somebody from Los Angeles or San Francisco or out of state, traveling on Highway 395, and they’re going to have the benefit of that crossing because there’s not going to be the deer running across the road.”

Near Lake Tahoe, for instance, three underpasses help mule deer safely wander below Highway 395. In Los Angeles County, the Harbor Boulevard Wildlife Underpass is a metal corrugated tunnel directing coyotes, deer and bobcats under the road. In Orange County, a corridor will provide a safe route for gray foxes, bobcats, coyotes and other creatures to travel between the Santa Ana Mountains and the coast.

Underpasses are generally cheaper than overpasses, and some animals, such as deer, prefer them.

Mountain lions, however, prefer overpasses. A desire to protect them from extinction has led to the years-long push to build the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing. Expected to be complete in late 2025, it will be the largest wildlife passage in the world.

Liberty Canyon overpass could save mountain lions

Mountain lions in the Santa Ana and Santa Monica Mountains face a 99% chance of extinction within the next 50 years, and genetic isolation is to blame.

“They’re inbreeding with each other, and they face this extinction vortex,” said Mari Galloway, the California program manager at Wildlands Network. “It’s shown in this kinked tail.”

The kinked tail is a familiar omen. A few decades ago, fewer than 30 mountain lions remained in Florida. Isolated by highways, they were breeding in too small of circles. The proof was in the tail: When on the edge of extinction, the ends of the tails were bent out of shape.

“What they need is genetic connectivity, and so Liberty Canyon will provide more opportunities for outside mountain lions to come in and really give that gene pool a boost and diversity,” said Tiffany Yap, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity in San Francisco. “Not only is that crossing really key for mountain lions, but it would help an incredible amount of biodiversity in the area.”

Connecting one side of the mountain range to the other, the crossing would provide a safe passageway for mountain lions as well as gopher snakes, mule deer, and desert cottontail rabbits.

The project — expected to cost $87 million — is being funded with public and private dollars, including $250,000 from the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and $25 million from the Annenberg Foundation.

“We’re not just relying on the state,” said Beth Pratt, regional executive director at the National Wildlife Federation.

The investments not only buoy conservation efforts, but also make highways safer and financially self-sustaining. In Placerville, in the Sierra Nevada foothills, a tunnel under Highway 50 cost $1.3 million to build.

“The project is pretty close to having paid for itself already by reducing collisions with deer,” said Shilling, the UC Davis ecologist.

Enticing road builders to plan for wildlife

Money, however, isn’t the only problem. Even if consistent funding went to wildlife crossings, actually building them can get complicated.

That’s because California’s transportation planners — under pressure to serve growing communities and alleviate traffic — haven’t had much incentive to build tunnels and bridges for animals. State Sen. Henry Stern wants to change that.

“We’ve got all these big statewide goals around biodiversity and protecting natural lands and conserving open space,” the Malibu Democrat said. “But we thought we needed to do something… that really integrated wildlife connectivity and habitat connectivity into the transportation planning process.”

Stern’s Senate Bill 790 creates an incentive system that allows Caltrans, the agency that builds roads and freeways, to get credits from the state if it retrofits highways with new wildlife crossings.

In the future, when Caltrans builds transportation projects that may have adverse environmental impacts, the department can draw upon these mitigation credits from building wildlife crossings. The concept is similar to other environmental programs that encourage companies to offset some of their pollution by paying for ecological benefits.

The bill passed the Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support and is now being considered in the Assembly.

The bill would also grant mitigation credits to Caltrans when its projects protect species listed under the California Endangered Species Act. Since October 2020, some mountain lions in Southern California and the Central Coast have been granted temporary legal protection under the act, while the state Department of Fish and Wildlife reviews whether they should be listed as threatened.

That means if Stern’s bill becomes law, projects such as Liberty Canyon could receive a boost because Caltrans could receive mitigation credits for building a crossing that helps mountain lions.

This issue also represents an opportunity for Newsom to advance his family legacy of mountain lion conservation. More than 30 years ago, his father William Newsom championed the ballot measure that banned hunting the species in California. The governor remembers licking envelopes to help promote his father’s hunting ban, he told the Sacramento Bee last year.

Stern talked with Newsom about his connection to mountain lions when they toured the site for the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing almost two years ago.

“This is how he and a lot of other people connect to nature,” Stern said. “He was out there with his dad helping get the original mountain lion ballot initiative passed… and he wanted to run around in the wilderness with me… and you could tell, it woke up the kid in him.”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.