CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

The state’s nursing home licensing system has long raised the ire of elder-care advocates.

Now, another misstep has sparked new frustration among both nursing home watchdogs and state lawmakers.

By its own admission, the California Department of Public Health incorrectly listed a controversial nursing home operator as holding permanent licenses for two Los Angeles-area nursing homes. Department officials failed to realize their mistake for five years, until advocates pointed it out this spring. Now department officials say they won’t fix it.

“Don’t you love it? Clerical error. That’s how you get a license for a nursing home,” said Dr. Mike Wasserman, a geriatrician and immediate past president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

The “data entry error,” documented in public records and department emails, is “just the latest example of how the state oversight of California’s nursing homes is completely broken and ineffective,” said Democratic Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi of Los Angeles.

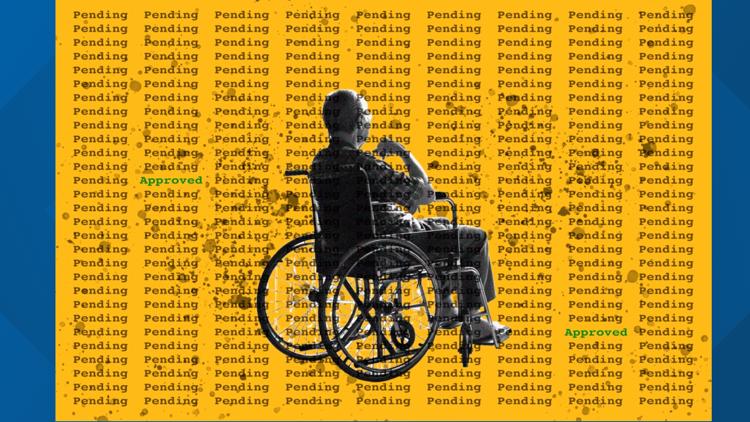

The error affected two in a group of 18 nursing homes known as Country Villa. A CalMatters investigation published April 6 revealed how the Department of Public Health for years had kept those homes in licensing limbo, failing to decide whether to grant their new owner the permanent licenses to operate them.

Los Angeles businessman Shlomo Rechnitz and his companies had acquired the 18 homes in 2014 in federal bankruptcy court, despite an emergency motion by then-Attorney General Kamala Harris to prevent the sale. In that motion, Harris referred to Rechnitz as “a serial violator of rules within the skilled nursing industry”— comments his attorney called “defamatory” and “outrageous,” according to bankruptcy court records.

The department told CalMatters earlier this year it had not decided whether to grant or deny Rechnitz the 18 licenses needed to officially run the Country Villa homes, instead leaving them all in “pending” status. The arrangement allowed Rechnitz and his companies to operate the homes for years under the license of the previous owner.

Advocates for nursing home residents have regularly raised concerns about the stalemate and about Rechnitz, the state’s largest nursing home owner, who through his companies has acquired at least 81 facilities with more than 9,000 beds.

When it comes to nursing homes, the department has broad reach. In California, the department is responsible for approving or denying nursing home licenses and ensuring that operators are fit to run these homes, which serve some of the state’s most vulnerable residents. The department also routinely inspects nursing homes to ensure they meet state and federal regulations.

In various letters to state public health officials, Patricia McGinnis, executive director of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, has called on the state to deny Rechnitz’ companies’ pending applications, saying the department “has created an environment where chain operators with deplorable records have virtual carte blanche to acquire more nursing homes in California.”

Mark Johnson, attorney for Brius, one of Rechnitz’ main companies, said Brius is aware that the licenses for the two facilities have been issued, and that it has no comment on the remaining 16 applications that are pending. But Johnson and his client have accused the department over the years of unfairly targeting Rechnitz and his companies – at one point complaining to state officials about the state’s “lack of communication, transparency and misrepresentations” in a 2015 email obtained by The Sacramento Bee

Representatives of Gov. Gavin Newsom, the attorney general’s office and the Health and Human Services Agency, which oversees the health department, declined to be interviewed for this story. All referred CalMatters back to the California Department of Public Health.

The department’s mistake was discovered last spring, when Michael Connors of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform spotted something odd on Cal Health Find, the Department of Public Health’s consumer website.

Emails shared with CalMatters show that Connors asked the state in a March 18 email why it appeared that Rechnitz’ companies held current licenses to operate several Country Villa homes.

Department officials said they’d look into it. Three months later, on June 29, Cassie Dunham, acting deputy director of the department’s Center for Health Care Quality, came back with an answer:

The state had not intentionally approved any of the licenses, she told Connors. But, five years prior, an employee had erroneously updated the database to make it appear, incorrectly, that Rechnitz’ companies were the current licensees for Country Villa South Convalescent Center and Country Villa Los Feliz Nursing Center.

Rather than fixing the newly discovered error, department officials doubled down, telling Connors via email that they had “determined that it cannot at this point reverse this error” and that they now considered Rechnitz’ companies to be the current licensees for the two homes.

In three unsigned emails to CalMatters, a spokesperson for the department confirmed the licenses were issued “erroneously.” Despite that, the spokesperson said the department “has no authority to take away this ‘property right’ that a permanent license conveys by now changing the license status back to pending.” The representative said that, because the issue arose due to a data entry error, the department has since “provided a refresher training for staff.”

Advocates, ombudsmen and at least one legislator are crying foul, pointing to this licensing-by-clerical-error as further evidence of the state’s weak and inconsistent oversight.

“Is that how much we care about nursing home residents?” asked Wasserman, the geriatrician who once worked as CEO of Rockport Healthcare Services, the administrative services company for many of Brius’ nursing homes. Wasserman has since become a vocal critic of the nursing home chain and its management, citing poor quality care and other concerns.

Said Connors of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform: “I don’t think there are words enough to describe how appalled we are about it. The fact that they have responded by affirming those licenses rather than doing something that would benefit the residents is just super troubling.”

Assemblymember Muratsuchi of Los Angeles called the state’s response “inexcusable.” Muratsuchi is the author of Assembly Bill 1502, which would require owners and operators to get approval from the state Department of Public Health before acquiring, operating or managing a nursing home.

That bill stalled in the Assembly Health Committee earlier this year and will not be heard before next year. Assemblymember Jim Wood, a Santa Rosa Democrat and chair of that committee, has said he will hold a hearing on nursing homes, including licensing issues, later this fall and told CalMatters he intends to put his name on the bill as a joint author.

Jerry Seelig, a state-appointed temporary manager of struggling nursing homes who served as the court-appointed monitor during the Country Villa bankruptcy case, said the department routinely fails to use its leverage to make change.

“No one can make any sense of this,” he said. “Zero.

“In those situations where they have leverage, which is Country Villa, they just bury their heads in the sand.”

Residents of the homes in question have been hit hard during the pandemic. Country Villa South – which has 87 beds – has had 185 COVID-19 cases and 26 deaths; Country Villa Los Feliz – which has 131 beds – has had 90 COVID-19 cases and 28 deaths. That puts both homes in the top 4% of homes statewide with the highest numbers of resident deaths due to COVID-19, a CalMatters analysis of state data found.

Country Villa South is rated one star out of a possible five stars by Medicare, a classification described as “much below average.”

State inspectors have cited the facility for infection control violations six times since March 2020, according to federal nursing home data. After several staff were confirmed positive for the virus that month, inspectors found the home deficient for failing to implement infection control protocols to stop the spread of COVID-19.

“These deficient practices had the potential to place all 75 residents of the facility at risk of contacting the COVID-19 virus,” according to the April 8, 2020, inspection report.

Problems in the home predate the pandemic. In 2019, the state fined the home $20,000 after a resident’s leg was caught under a wheelchair with an unsecured leg rest, and fractured badly enough to require surgery.

Molly Davies, the Los Angeles County long-term care ombudsman, whose office advocates for residents of nursing homes and other adult care facilities, said she’s also heard many complaints about Country Villa Los Feliz, despite the fact that that home’s rating recently increased from two stars (“below average”) to three (“average”).

In 2019, the state fined the facility $2,000 after a patient with Alzheimer’s wheeled himself out of the facility through a propped-open emergency exit, rolled down a steep ramp, fell out of his wheelchair and hit his head on the street.

Davies calls the idea of the state accidentally granting licenses to operate nursing homes “unfathomable.”

“It just continues to speak to the farce that is the regulatory enforcement system of skilled nursing facilities in California,” she said.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

RELATED:

ABC10: Watch, Download, Read

Watch more from ABC10:

The Price of Care: Investigating California's Conservatorships