CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published in CalMatters

Nearly three years after being released from state prison for defrauding the government, Attila Colar saw a new opportunity to pull in steady money from California taxpayers.

He didn’t even need to hide his criminal past when he applied for a contract with a California rehabilitation program for parolees leaving state prisons. Former felons are welcome as landlords in the state-funded rehabilitation program, and many have a strong history providing services to their tenants. But he covered up his record, anyway.

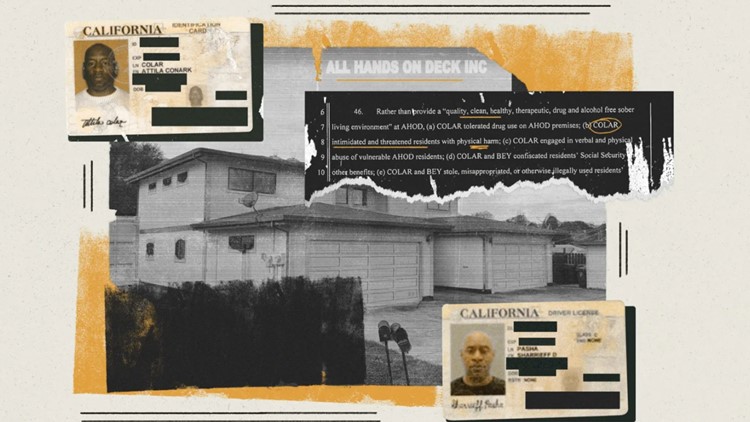

Using one of his five aliases, Colar, 51, eased through the vetting process at the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation in the fall of 2019.

The nonprofit he created, All Hands on Deck, then joined the list of companies entrusted with helping parolees stay out of trouble and get back on their feet through the state’s Specialized Treatment for Optimized Programming, known as STOP.

But Colar didn’t make good on those promises. Instead, he used the names of tenants and other false identities in a scheme to claim $1 million in fraudulent COVID-19 relief benefits, as a federal jury would later find. He “falsely represented that the residents were CEO’s of companies with hundreds of employees with million-dollar payrolls,” the U.S. Justice Department said in announcing his conviction.

That wasn’t all.

Prosecutors alleged in the indictment — and two former residents also told CalMatters — that Colar physically abused residents who were former prisoners enrolled in the parolee program as well as people with mental health disorders living on fixed incomes. Although prosecutors did not charge him with abuse or present evidence of it at trial, in the indictment they painted a picture of life inside the two Contra Costa County homes Colar operated. In addition to engaging in “physical abuse” of residents, he “tolerated drug use … confiscated residents’ Social Security and other benefits,” and ignored their medical needs, according to one of the many counts in the indictment for which he was convicted, conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

“It was like inmates running it,” said a former parolee who once lived at the home and spoke to CalMatters on condition that CalMatters not name him out of concern for his safety. “I ended up relapsing,” he said, adding that he was sent back to prison.

Colar, who is also known as Dahood Bey, is being held without bail as he awaits sentencing. He faces up to 220 years in prison after the jury in June found him guilty of 44 felony counts, including wire fraud, bank fraud, identity theft, being a felon in possession of a firearm and ammunition, and witness tampering.

His co-defendant and longtime companion, Jameelah Bey, pleaded guilty to five counts — aggravated identity theft, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, conspiracy to commit wire and bank fraud, obstructing an official proceeding and witness tampering — and testified in Colar’s trial.

Court records, including trial exhibits and Bey’s recently unsealed plea agreement, detail how Colar scammed state officials and contractors for a couple of months before anyone caught on.

Invoices included in the court records show that a state contractor continued paying Colar thousands of dollars a month to house former prisoners through a second parolee reentry program well after an employee alerted corrections department officials to suspected fraud. The contractor moved some tenants out of the homes Colar operated right away, but the state did not remove all of them until after Colar’s indictment and arrest.

After CalMatters asked the department about the state’s delayed removal of parolees from the homes, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said the agency would respond better in the future. The spokesperson acknowledged that the department did not relay concerns about Colar to the second parolee program.

“Moving forward, if (the Division of Rehabilitative Programs) becomes aware of issues with a subcontractor that requires the removal of participants, it will cross-reference subcontractors across all contracts to ensure participants are removed immediately and/or not placed at any associated facility for all community programs,” wrote department deputy press secretary Pedro Calderón Michel.

Colar’s scheme, as detailed in the indictment and for which he was convicted, depended in part on his exploitation of California’s largest parolee reentry program, STOP, which serves about 8,500 people a year and costs $100 million annually. The program is meant to give parolees a soft landing outside of prison, but it has operated with little oversight for years. A separate yearlong CalMatters’ investigation found that state officials — after spending more than $600 million on the program since 2014 — cannot say if it has helped steer newly released prisoners away from crime or find jobs.

Our report detailed how the corrections department leaves most of the program’s operations to four large contractors — GEO Reentry Services, Amity Foundation, HealthRight 360 and WestCare California. They in turn hire subcontractors who provide housing and services to parolees. All Hands on Deck was one of them.

For about two-and-a-half months of work providing housing and some rehabilitative services, Colar collected $81,188. That stream of revenue ended for him after STOP service provider GEO Reentry realized that All Hands on Deck had submitted fake fire inspection certificates, according to trial exhibits. The fraudulent documents — which sent GEO Reentry and the state scrambling to move parolees out of Colar’s reentry homes — was the first red flag that would eventually lead to the unraveling of All Hands on Deck.

Prior to the trial, Colar filed a motion to dismiss the case. It was rejected by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. CalMatters reached out to him by mail. He responded with a phone call from Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, first agreeing to answer questions about the STOP program but, before doing so, saying he would have to call CalMatters back. He has not.

Colar represented himself in court, where in an opening statement he denied defrauding the government and GEO. He said he worked around-the-clock to serve parolees.

“I don’t know how you can defraud GEO Group when we worked day and night,” he said. “They expected us to work 24 hours around the clock for a little bit of money.”

He said prosecutors were “telling half truths to make me look bad,” according to a trial transcript. “I’m not no golden boy, either,” he told the jury. “I’m not saying that I walk straight on the path.”

Colar said the federal government clawed back the money All Hands on Deck took in from the Paycheck Protection Program.

“No money was lost,” he told jurors.

He also acknowledged having physical conflicts with residents, although he said he was defending himself after the state contractor GEO Reentry sent violent people to the properties he ran.

Abuse, fraud charges in East Bay

Colar’s decades-long record in East Bay courtrooms was a prelude to the federal charges he faced stemming from his work with parolees.

The cases dating to 2002 include pleas of no contest over allegations that he threatened an ex-lover’s romantic partner, beat up a tenant at a property he rented, falsified DMV records, and later used fraudulent documents to win security services contracts with government agencies throughout the state.

Colar once worked as a baker, driver and bodyguard for Your Muslim Bakery, according to The Chauncey Bailey Project, a news group that covered the fallout after Oakland Post editor Chauncey Bailey was killed in 2007.

Colar’s co-defendant in the current case, Jameelah Bey, also worked for the bakery, where she taught third through 12th grade girls, according to details from her plea agreement. Bey told federal prosecutors that she was one of several wives to bakery founder Yusef Bey. He died in 2003 before his trial for lewd conduct with a minor, the Chauncey Bailey Project reported.

The Oakland-based dessert-seller folded in 2007 as it faced bankruptcy and accusations that its leader ordered the killing of the journalist, who was looking into the operation’s finances. The bakery’s leader at the time, Yusef Bey IV, the founder’s son, was convicted in 2011 of orchestrating Bailey’s killing and was sentenced to life without parole.

After the bakery’s collapse, Colar led an organization called Black Muslim Temple that operated a security firm and janitorial service, according to court records.

He and others affiliated with the temple submitted fake documents — such as false descriptions of their insurance coverage, work experience, education and military service — to get public contracts with the Port of Oakland, the Housing Authority of Los Angeles and other California government agencies between 2011 and 2014, the judge in the case said while sentencing Colar, court transcripts show.

In 2015, Colar and the others pleaded no contest to filing false documents and several felonies, which is punishable as if pleading guilty. Jameelah Bey, Colar’s co-defendant in the COVID-19 loan fraud case, also pleaded no contest to charges in the 2015 fraud case.

Colar was sentenced to five years in state prison and served about two: one in prison and one in jail.

Before his release, the mother of Colar’s children filed and won a temporary restraining order against him, according to a filing with the Contra Costa County Superior Court.

“As (Colar) gets closer to being released from prison, he is becoming increasingly more verbally aggressive. All signs of his former violent, intimidating, manipulative ways are resurfacing in conversation,” she wrote to the court. When requesting a no-travel order for the children, she said, “he will falsify documents to sway an outcome to his advantage.”

Colar was released on Dec. 27, 2016, less than eight weeks after the judge issued a temporary restraining order.

How he won another California government contract

By 2019, he was on to a new venture: All Hands on Deck.

The nonprofit described its mission as providing “housing to men getting out of prison, food bank services, life and work skills,” according to the company’s certificate of incorporation. It would use homes in El Sobrante that Colar’s family has owned since the late 1990s.

One of the company’s target customers was the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which funds several programs to help parolees adjust to life after prison.

With some exceptions, the STOP program welcomes former prisoners to manage homes and services.

“A CEO’s criminal past is not an automatic disqualifier from consideration,” wrote Monica Hook, GEO’s vice president of communications, in an emailed response to CalMatters. GEO Reentry Services is a Florida-based for-profit company that manages STOP providers for the state corrections department.

“In fact, some of our best service providers are formerly incarcerated individuals,” Hook wrote.

The only crimes precluding someone from working with the STOP program are “drug trafficking in a prison/jail, escape or aiding/abetting escape, battery on a peace officer or public official, or … unauthorized communications with prisons and prisoners,” wrote Terri Hardy, a department spokesperson.

Nonetheless Colar’s application for a state security clearance — which identified himself as the program’s house manager using his legal name and birthdate — did not include his previous arrests, the signed form shows. The form listed someone else as the nonprofit’s executive director: one of Colar’s aliases.

A decade of court records from his previous criminal cases in which he pled no contest detail how Colar became an expert in aliases — an expertise that would come in handy once he got the state contract to rehab parolees.

He used two names when forming his company, All Hands on Deck, in Delaware. One was his legal name; the other was the alias David Lee. As the indictment laid out, both names were listed in the company’s bylaws as “Incorporators."

Nearly two weeks after All Hands on Deck registered with California’s Secretary of State, Colar — using the alias Sharieff Pasha — and other representatives of the company, applied to participate in the STOP program as a landlord and service provider, according to the application filed with GEO Reentry Services.

Although Colar incorporated the company, another person signed the application as All Hands on Deck’s CEO. Colar was listed as the company’s director, and Jameelah Asma, court records said is an alias for Jameelah Bey, was the company’s assistant director, the application shows.

The indictment later noted that Colar in late 2019 opened a bank account for All Hands on Deck as the company’s chief executive officer, treasurer and secretary — the “sole signatory on that account.”

STOP contractor GEO agreed to pay All Hands on Deck up to $100 each day per person for housing and food, up to $125 per person for one hour of individual therapy, and up to $95 per person for two hours of group sessions for outpatient treatment.

First signs of fraud in California rehab home

When the first parolee moved into an All Hands on Deck reentry home on New Year’s Eve, Colar’s nonprofit still had not obtained the certification or license from the state Department of Health Care Services that its contract required. According to evidence from the trial, All Hands on Deck in June 2019 told GEO that its certification was pending. Four years later, the department told CalMatters it never received an application from All Hands on Deck.

A list of summary testimonies of prosecution witnesses filed with the court for Colar’s trial described how a maintenance man was once listed as the company’s nurse practitioner; a security guard was also once listed as the housing director.

Problems followed soon after move-in day.

GEO Reentry reprimanded All Hands on Deck for discharging a resident without explaining why, signing up residents for unnecessary services, inaccurate charges and enrolling parolees in the program without approval by GEO, as the contract required, court records show.

But it really began to crumble after GEO discovered fake fire inspections, in which the fire district’s name is misspelled, from the All Hands on Deck homes in El Sobrante, GEO and Colar emails admitted as evidence in his case show.

“Our biggest concerns are that (All Hands on Deck) sent us phony documents and have participants sleeping in uninspected housing, potentially unsafe,” Diane Harrington, GEO Reentry’s STOP Program director, wrote on March 9, 2020 in an email to All Hands, copying a corrections department employee. “For certain, we are not sending any new placements with this unresolved.”

In an email signed with one of Colar’s aliases, All Hands on Deck denied knowing anything about the forged documents. The message said a board member had been “trying to sabotage our company and business relationships” and the company email was “taken over” by the person.

That information did not alter GEO Reentry’s efforts to quickly move eight STOP parolees out of the homes Colar ran.

“We really need … moves to take place tomorrow,” Harrington wrote in an email to her colleagues and corrections department employees.

As parolees from the Colar site moved into other STOP-funded homes throughout the Bay Area, stories about All Hands on Deck began to trickle out.

One parolee told a GEO employee that a man using the name of one of Colar’s aliases took “cash from his wallet” … after the parolee was “fined $250 for allegedly making a hole in a wall,” Harrington wrote in an email to All Hands on Deck on April 13, 2020, according to court records. The resident “was not provided with a receipt when the cash was taken form (sic) him, giving the appearance of impropriety.”

In a reply email to GEO and the department employee, someone from All Hands on Deck denied the allegation: “(The former resident) is disgruntled and angry because we reported an incident to … his (parole agent) about his substance abuse problem.”

The email exchange underscores the problematic power dynamic inherent in a program that places parolees under the supervision of a taxpayer-supported landlord, one advocate said in an interview with CalMatters.

“It’s extremely difficult to go through a process where you know you’re being harmed, but it’s better to stay silent,” said Kelly Savage-Rodriguez, program coordinator at California Coalition of Women Prisoners. “If you speak up in this area, you could be removed from the program and have nowhere to live.”

More parolees, and $1 million in COVID fraud

Email exchanges and invoices included in trial exhibits show that while GEO Reentry and state officials moved STOP participants away from Colar’s site, GEO and the state allowed parolees under a separate state-funded parolee program to stay.

The Day Reporting Center is another state parolee reentry program paid for by the corrections department. It “offer(s) an array of services designed to increase the success of at-risk parolees discharging from correctional institutions,” according to the department’s website.

All Hands on Deck charged taxpayers $35 per day for every Day Reporting Center parolee the company housed.

The nonprofit billed $45,764 for nearly 10 months of work under that program, according to the indictment that led to Colar’s conviction. The money kept coming until December, nine months after GEO identified the fraudulent fire inspections and began moving parolees out of the STOP program.

As Day Reporting Center parolees continued living at the reentry home, Colar began his scheme to get COVID-19 relief loans through the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program.

He listed others including his boarders — those living on the taxpayers’ dime — as his staff, inflating All Hands on Deck’s employee roster to 81 people and the company’s monthly payroll to nearly $800,000, the jury found.

In reality, the company had no salaried employees except Colar himself, as the U.S. Department of Justice noted in heralding his conviction.

Colar started applying for those federal program loans in April 2020, ultimately filing 16 fraudulent loan applications seeking $34 million for All Hands on Deck and several companies, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. He received about $1 million in payments, the indictment says, before the feds came knocking.

Colar “targeted some of the most marginalized and dispossessed persons in our community. Their badly needed cash went into the defendant’s pocket. In the end, the defendant manipulated the very people who came to him for help,” U.S. Attorney Ismail J. Ramsey said after Colar’s conviction.

New charge: Witness intimidation

Colar first appeared in court in the COVID-19 fraud case in September 2020, when federal prosecutors charged him. At that time, five Day Reporting Center parolees were living at All Hands on Deck, invoices and court records show.

Weeks later, GEO decided to cut ties with its troubled subcontractor, according to messages contained in trial exhibits. “As of 12/27/2020, GEO will no longer need to use All Hands on Deck transitional housing services,” wrote Mahnoor Tariq for GEO Reentry Services, in a contract termination letter to All Hands on Deck.

On the final invoice, GEO Reentry accused All Hands on Deck of “wrongfully” charging for the program.

“Please pay $560 only,” wrote Tariq on the invoice stamped on Jan. 25, 2021. “Being wrongfully charged $945 for (a parolee). Vendor refusing to take it off invoice.”

By that time, federal prosecutors were digging in and learning more about the company.

One former tenant told CalMatters that his experience in the home traumatized him.

“I’ve been hurt, beat up, stabbed, punched, pushed, hit, yelled at, attacked,” said the tenant, who spoke to CalMatters on condition that CalMatters not name him out of concern for his safety. “I have a lot of anger towards them. They shouldn’t have done what they did. I think they should be punished but karma is going to catch up with them … God will get them,” the former tenant said.

U.S. attorneys expanded their accusations in April 2022, adding Jameelah Bey, plus her four aliases, as a co-defendant.

That document included another charge against Colar and Bey, alleging that they attempted to intimidate a witness by preventing that person from appearing before the grand jury.

Prosecutors wrote in the indictment that Colar and Bey had “a doctor’s letter transmitted to the United States Attorney’s Office with the intent to influence, delay, and prevent” a former resident from testifying, the indictment says.

That doctor’s letter didn’t stop the prosecution. Bey copped to the charge, pleading guilty. The jury Colar faced found him guilty of that charge, too.

In her plea agreement, Bey admitted to trying to defraud GEO Reentry and the government. She also told prosecutors in a written statement submitted to the court that she committed many of her crimes at Colar’s direction, adding that he abused her throughout their 15-year relationship.

Bey said she knew what she was doing was wrong, but felt “compelled to do them given (her) relationship — and personal domestic violence history — with Mr. Colar.”

“I also engaged in this wrongdoing because Mr. Colar used the cash from (All Hands on Deck) to pay for our home and fund the life we were building with the kids.”

As Colar awaits his sentencing in Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, All Hands on Deck has shuttered. Boarders are still renting rooms inside the homes his family owns.