CALIFORNIA, USA — Former President Donald Trump won a second term after four years out of the White House, likely thrusting California back into leading the resistance against him.

The Associated Press made its call at 3 a.m., declaring that the Republican defeated Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris, who would have become the first woman president and the most powerful Californian in four decades.

Instead, Californians now face a repeat of Trump’s first term from 2017 to 2021 — another four years of governance consumed by combative showdowns between the state’s Democratic leadership and Washington, D.C., possibly distracting from or even setting back progress on addressing California’s own problems.

Though many were rooting for a Harris victory — which could have taken California’s priorities nationwide and brought additional resources home — state officials, industry leaders and activists prepared for this outcome. Trump, after all, routinely made California a punching bag in his campaign.

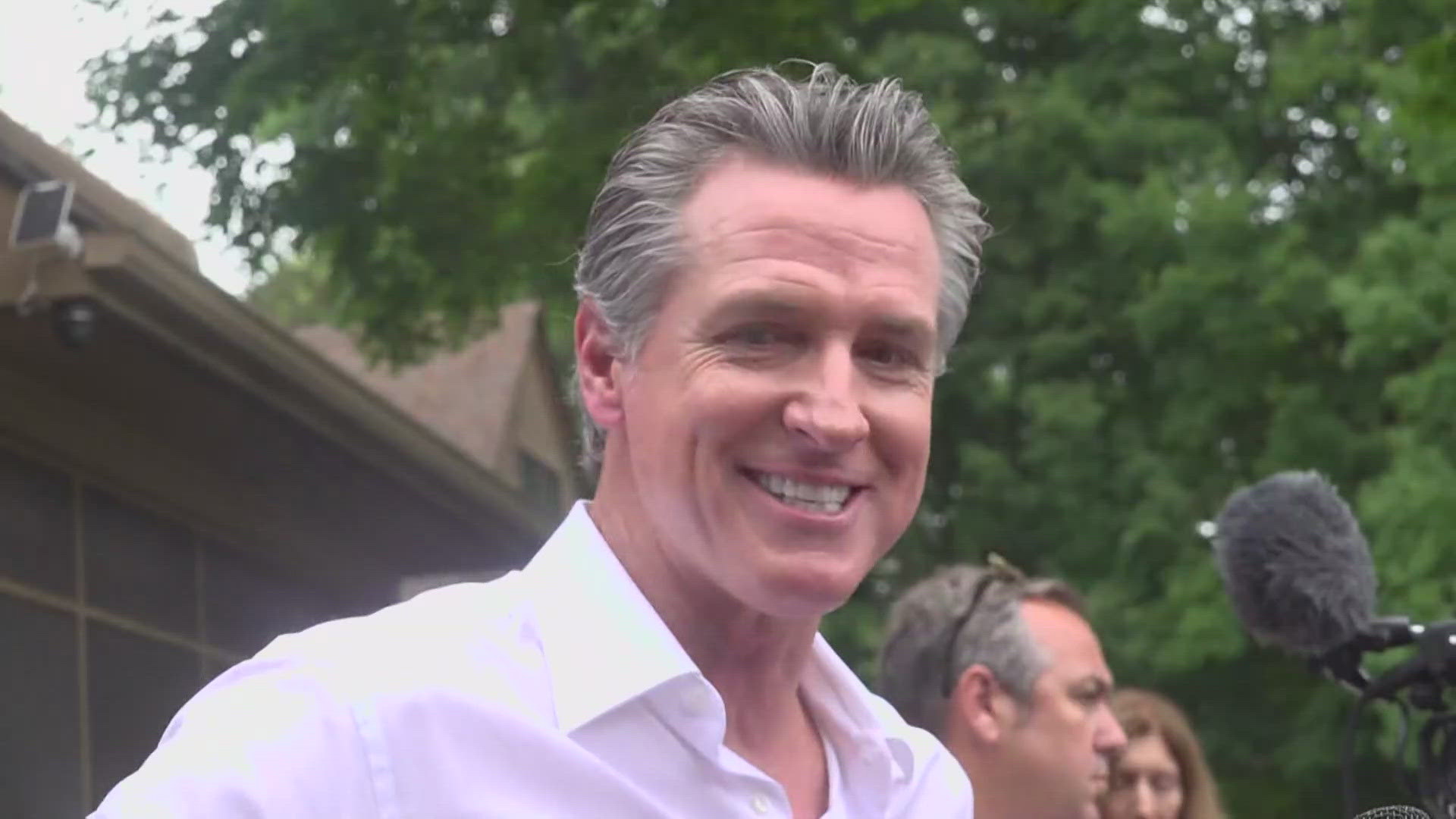

Across state government, officials have been gaming out a response to “Trump-proof” California. Gov. Gavin Newsom and his budget team are developing a proposal for a disaster relief fund after the former president repeatedly threatened to withhold emergency aid for wildfire recovery from California because of its water policy.

“The best way to protect California, its values, the rights of our people, is to be prepared, so we won’t be flat-footed,” said Attorney General Rob Bonta, whose team has been working with advocacy organizations and attorneys general in other states on how they would answer another Trump administration. “We will fight as we did in the past if that scenario unfolds.”

During Trump’s first term, California sued more than 100 times over his rules and regulatory rollbacks. Bonta said his team has preemptively written briefs and tested arguments to challenge many of the policies they expect the former president to pursue over the next four years: passing a national abortion ban and restricting access to abortion medication; revoking California’s waiver to regulate its own automobile tailpipe emissions and overruling its commitment to transition to zero-emission vehicles; ending protections for immigrants brought to the country illegally as children; undermining the state’s extensive gun control laws, including for assault weapons, 3D-printed firearms and ghost guns; implementing voter identification requirements; and attacking civil rights for transgender youth.

“Unfortunately, it’s a long list,” Bonta told CalMatters days before the election. “We are and have been for months developing strategies for all of those things.”

California takes on Trump

In many ways, California is more protected from swings in federal regulations than other states, because it has a robust regulatory framework of its own that often goes much further than the federal government.

Lorena Gonzalez, president of the California Labor Federation, said unions see an ongoing challenge to the constitutionality of the National Labor Relations Board as a much bigger threat than any actions Trump might take. California law is already stronger than federal law on minimum wage, overtime pay and wage theft protections.

“He can’t do anything through the Department of Labor that would undo that,” she said.

But with Democrats in control of every state office and holding supermajorities in both chambers of the Legislature, Trump’s victory could completely upend policymaking in California.

During his first term, legislators focused on counteracting his federal agenda — though not always successfully. California’s governors in that period, Newsom and Jerry Brown, took executive actions to limit the fallout of his rollback of environmental regulations, including launching a pollution-tracking satellite and negotiating with auto companies to maintain higher mileage standards.

Newsom’s office declined to discuss the stakes of the presidential election — although at a press conference last week, he said “no state has more to lose or gain in this election” than California. Nor did representatives make Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuire or Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, both Democrats who will shape the legislative agenda and state budget next year, available for interviews.

A return to open conflict is a worrisome prospect for the business community, which was often caught in the middle of federal and state rules during Trump’s first term — such as with a 2017 law that restricted employer participation in workplace immigration raids.

“Having the state react, it sort of puts things in limbo,” said Jennifer Barrera, president and CEO of the California Chamber of Commerce. “When the two aren’t aligned, it creates some problems for our members that operate on the national level.”

How far will California go?

As Democrats look to protect California’s liberal values, there is concern they will resist Trump’s plans by going further in the opposite direction, in potentially counterproductive ways.

Federal regulations make only a marginal difference in the cost of housing in California, according to Dan Dunmoyer, president and CEO of the California Building Industry Association, but he fears the state’s response could unintentionally undermine its efforts to boost construction. In 2019, as the Trump administration narrowed federal water protections, California adopted even more expansive state regulations that developers complained made it more complicated and costly to get building permits.

“The anti-Trump factor is real,” Dumoyer said. “I expect that if Trump says the sky is blue, they’ll say it’s black today.”

Divided partisan control could also further gridlock Congress, setting up the nation’s largest state as the battleground for major policy fights, especially in areas that are not of interest to Trump.

Adam Kovacevich, founder and CEO of Chamber of Progress, a left-leaning tech industry association, said advocacy groups seeking more oversight of the industry have been very active in Washington, D.C., for the past four years and enjoyed a lot of success with the Biden administration. Under Trump, they will turn to California to lead the way on regulating artificial intelligence and children on social media, as well as enforcing antitrust law.

“Congress is an environment of legislative scarcity,” he said. “California is an environment of legislative abundance.”

Trump is also viewed by the tech industry as a wild card who might punish major companies that he believes opposed him, Kovacevich said. Such a contentious relationship could hurt their profits — and then California’s tax revenue.

“It’s tech industry success that plays a huge role in funding the state’s social safety net,” he said.

Immigrant community on the defensive

With Trump’s campaign heavily emphasizing tougher enforcement of the U.S.-Mexico border and mass deportations, California’s large immigrant community — millions of whom are undocumented — has been plunged into an especially uncertain and terrifying moment.

As Newsom put it last week, “the impacts from valley to valley, Silicon Valley to Central Valley, will be outsized” — particularly if Trump also revives his push to limit legal immigration, including by refugees, foreign workers and international students.

The California Immigrant Policy Center, an immigrant rights advocacy group, has already led 15 scenario-planning exercises with hundreds of people from organizations across the state to prepare. “We know that the Trump administration is going to target California. They’ve been targeting California throughout this election cycle,” Masih Fouladi, executive director of the group, said. “We need to do a lot in California to make sure that we are defending, protecting our communities.”

Under Trump, Fouladi said, immigrant rights groups would lobby to make sure state and local resources are not used to detain and deport people and that non-citizen residents continue to have access to health care and other public services, which the state has significantly expanded over the past decade.

One likely priority is strengthening the California Values Act, the 2017 “sanctuary state” law that limited police cooperation with federal immigration authorities. After a contentious legislative battle, the version that passed was scaled back from what supporters originally envisioned, exempting people convicted of hundreds of more serious crimes from the protections and allowing state prison officials to continue handing over individuals facing deportation orders.

“What we hope for is to address the rights of the immigrant community in a humane way,” Fouladi said.

This article was originally published by CalMatters.