SACRAMENTO, Calif — It’s a hot Monday afternoon and Alma Jimenez’s AC is running full speed in the room where her 7-year-old son, Abraham, “goes” to virtual school in their Concord apartment. Jimenez sets up the video call and sits a few feet away, ready to intervene if Abraham loses focus, as she knows he will. She will spend the next six hours tending to Abraham’s educational needs.

Unlike some parents, Jimenez can’t work from home: She’s a house cleaner. She’s also a single parent. And the bills are piling up.

“COVID-19 got me by the neck,” she says in hushed Spanish.

Until the pandemic, Jimenez was raising an astute, bilingual child on her own, making about $22,000 a year. The job’s still hers, and she needs it more than ever, but there’s no one else to watch her son. What’s she supposed to do, she asks, go and leave him alone all day?

Virtual school is testing the limits of families of all shapes and sizes as they try to juggle the roles of worker, teacher, and parent. But few are being tested like single parents who can’t afford not to head to their essential jobs every morning. Many are facing the hardest choice of their lives: prioritize their children’s education and survive without their usual income or choose their jobs to pay the bills.

Nearly one in six parents in the U.S. is raising a child alone. Many are caring for more than one: A quarter of the country’s children live with a single parent. Among Black children, it’s nearly one in two.

“Parents were struggling before, and the Bay Area is so expensive to live in, two working parents is necessary,” said Julianne Rositas, manager for a parent advisory program at Family Paths, an Oakland-based nonprofit serving families in five languages.

More than 8 million Californians have filed unemployment claims since March, and as the pandemic continues to shed jobs, households with two incomes are becoming less frequent. Rositas remembered two single mothers who were roommates. One lost her job, and the other was an essential worker who couldn’t decide whether to pay rent or utilities. Without internet, the moms knew, there is no school.

It takes a lot to make virtual school work.

“Imagine being five years old trying to do Zoom by yourself. It’s impossible,” said Aponi O’Keefe, a graphic design student who took up pod teaching during the pandemic. “You need constant supervision, someone to instruct breaks, lunchtime, playtime, a schedule of some sort that resembles a school day.”

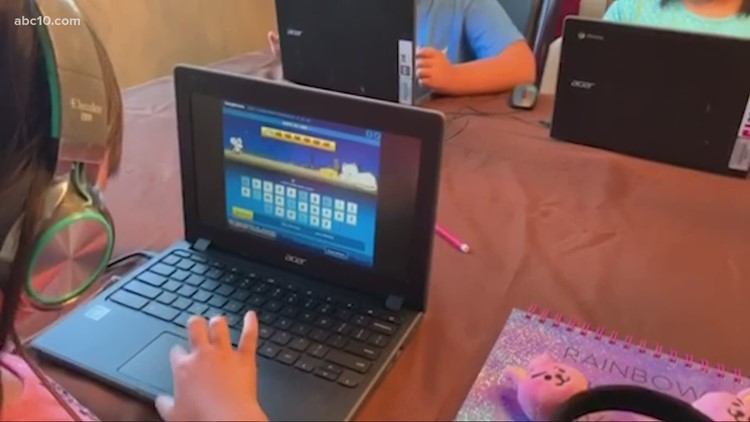

Even those with the luxury of working from home find it difficult. Many are doing their remaining work after putting the kids to bed. Others struggle to help with academic courses they learned decades ago, which are now taught via apps and games. For first-generation immigrants like Jimenez, it means teaching a language they’ve never studied. She translates Abraham’s homework with a cellphone app every time she wants to help.

“What is happening right now is the teacher is having to summarize the syllabus to the parent so they can be able to teach it,” said Daniel Castrillon, a 20-year-old virtual school instructor in Berkeley.

Self-employed tutors and educators say dozens of Bay Area parents seeking help with virtual school have responded to each of their online ads. “Some parents have just opted out altogether and chosen to send them to camps or learning pods outside,” said Christine Chen, the director of a software company, mother of two, and head of communications for Golden Gate Moms, a social group of 4,000 Bay Area moms.

“I totally understand why schools are online, but I don’t understand how any single parent – or how any parent – is expected to work and be their kid’s teacher right now,” said Kathryn Reeve, a master’s student at San Francisco State University and part-time tutor since March. “There’s definitely a divide between families who have resources and more space and can hire.”

Castrillon said he supervises a young boy whose mother — a single parent — works as a software engineer. The boy also has a tutor who specializes in specific academic topics, while Castrillon’s job involves supervising virtual class and helping with school work from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., five days a week.

Jimenez can’t afford tutors, child care, or someone to watch over Abraham’s classroom time, which can cost anywhere from $25 to $100 an hour.

For a “modest yet adequate standard of living,” the Economic Policy Institute estimates that a parent like Jimenez would need to make $8,221 a month, or $98,652 a year. She currently makes $400 monthly working a Friday shift, thanks to Abraham’s school, which is off most of that day so she can leave him with a cousin who agreed to watch him occasionally. With the $100 she makes each week, Jimenez has to pay for food, gas, insurance, internet, and school supplies for the week. She often has to cut down on food and she’s late multiple months on her PG&E bill.

“Every dollar that I earn, I look at how I should spend it,” she said. “Before it was down to the dollar, now it’s every penny.”

Abraham’s classroom is in the living room, which doubles as Jimenez’s bedroom. On the wall are some of Abraham’s drawings. “I want to be a Youtuber,” one reads.

Jimenez hasn’t been able to make her $1,420 rent since May, when the cleaning company she works for lost all but two clients. Late in the summer, she said, business started to pick up, but virtual school had started. While some Bay Area elementary schools have successfully applied to return to in-person school, Jimenez said Abraham’s hasn’t mentioned reopening plans. She is bracing for yearlong virtual school.

“You have to choose. I can’t pay my rent, but my boy is doing well,” Jimenez said. “Education comes first.”

Jimenez has gotten some help: a $500 check from the state’s Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants project, and the same amount from Monument Impact, a nonprofit serving low-income and immigrant communities in Concord. She also received a one-time boost of $365 for groceries from the program for children eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. But the help has dried up.

She and her son are currently staying housed thanks to Contra Costa’s local eviction moratorium, which was extended until January 31. Jimenez started a GoFundMe page seeking help and has been studying bookkeeping and administration online. At this pace, she’ll become a self-employed tax accountant by January — a job she can do from home. The trick will be staying housed until then.

"It’s often too much to handle for one mom," Jimenez said. “It feels like the whole world and I’m alone carrying it.”

This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.

WATCH MORE: Elk Grove Unified preparing for in-person learning as Sacramento County eases restrictions