CALIFORNIA, USA — On Tuesday, the California State Senate is set to consider a bill to amend the state’s constitution to remove “involuntary servitude” as a protected form of punishment, a move aimed at formally severing vestiges of slavery from the law.

Involuntary servitude describes a person who works for another, against their will through some form of coercion or imprisonment, regardless of pay. Like the U.S.’s 13th amendment, California is one of 20 states where involuntary servitude is allowed as criminal punishment.

California is the latest state to change its laws in a movement across the country. Colorado first removed the term from its constitution in 2018.

Advocates who want to abolish “involuntary servitude” say it is slavery by another name and flies in the face of rehabilitation.

ABC10 took an intimate look at the abolition act, sitting down with the original author of the bill. He wrote it while behind bars, and now released from prison, he is determined to not only right wrongs through education but the state's constitution as well.

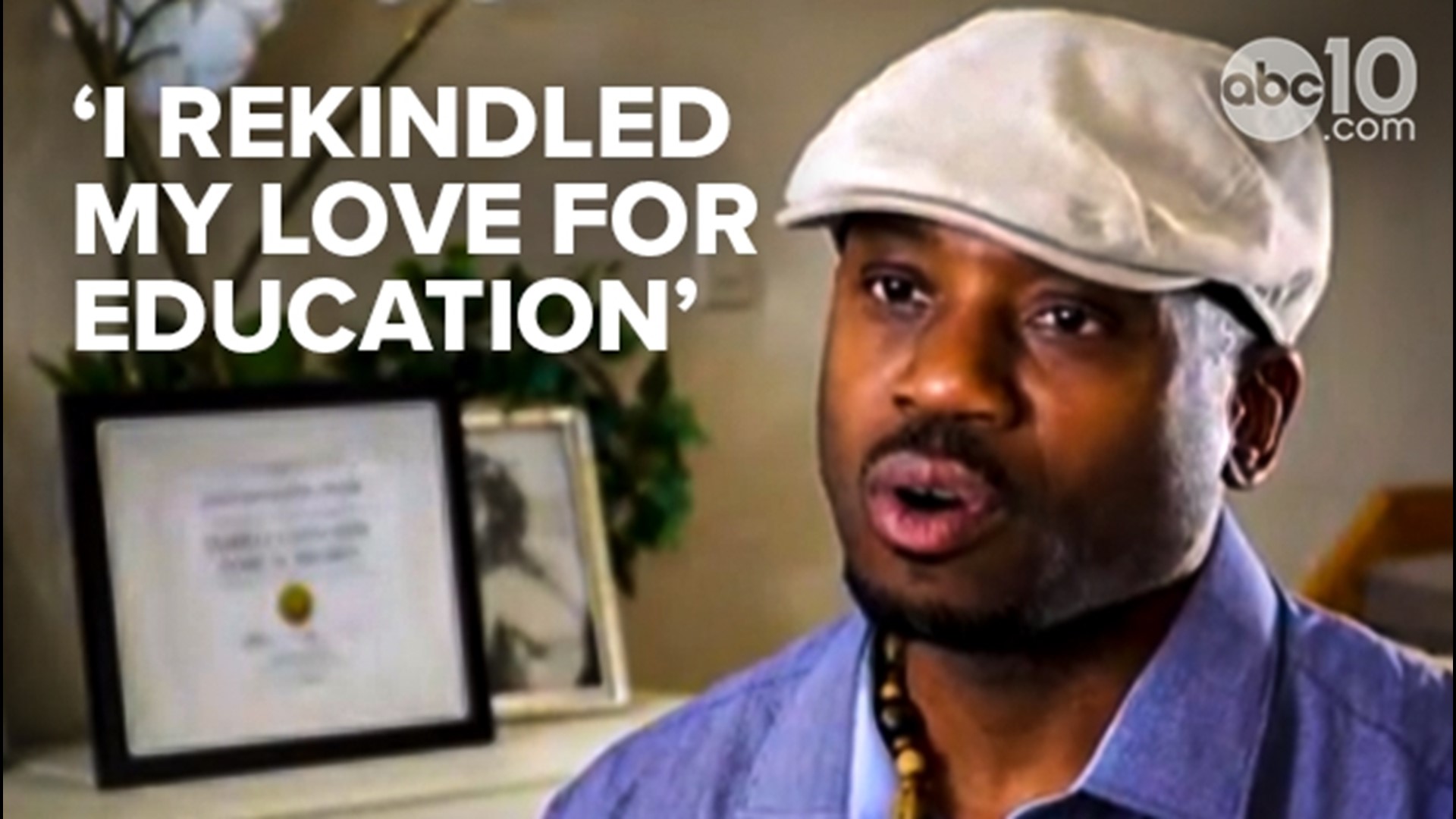

If you had asked Samual Brown, 24 years ago, if he’d be a father, husband, and community activist with three college degrees, he’d probably say, “No way.”

Back then, when he was a high school graduate set to attend Sacramento State University, he instead was facing two life sentences.

“I derailed it,” Brown said. “I was incarcerated for 24 years for the crime of attempted murder.”

Brown was convicted and entered California’s prison system in 1997.

“I lost respect for education prior to going to prison,” Brown said. “I didn't see how education was going to extract me from my immediate surroundings.”

Brown is now among 37 students who have graduated from California State University Los Angeles’ Prison BA Initiative. He earned a bachelor’s degree in communications last October while incarcerated at the maximum-security state prison in Lancaster. The program, aimed at reducing recidivism, was born at Cal State LA’s Center for Engagement, Service, and the Public Good (CESPG) in 2016.

Prior to enrollment, Brown had earned two associate degrees and created emotional literacy programs for fellow inmates. When he entered prison, he said there were no signs pointing to rehabilitation. It took several years of introspection and reading on his own.

“I rekindled my love for education,” Brown said. “Education is a powerful transformative tool.”

Dr. Taffany Lim is the executive director of Cal State’s CESPG. She says the Prison BA Initiative is more than just a piece of paper or a diploma. When she asks her incarcerated students what they’ve learned in `the program, she said, “It's not a specific teacher. It's not theory. The majority of the students will say the most important thing was that I was treated as a human and that has led also to a sense of hope, and a sense of transformation and their ultimate rehabilitation.”

After serving 24 years, Brown was released in January 2022, but he says getting home and achieving ultimate rehabilitation was a battle.

“Inside the prison system is forced labor over rehabilitation,” Brown said.

Brown says despite his work developing emotional literacy programs for fellow inmates, good behavior, and thousands of hours of self-help programming, his chance of release was predicated on his labor.

“You know, the prison is the modern-day plantation and '1-15' or '1-28,' the equivalent of the modern-day whip,” Brown said.

He is referring to forms added to inmates’ central files for misconduct and violating rules. He explains it this way from his most recent experience as a hospital janitor at the state prison in Lancaster: “I was required to be on the front line with COVID-19 hit,” he said.

It’s where the first California inmate tested positive for the virus. Brown said his job required him to clean infected areas of the jail.

“It's one of the higher-paying jobs. I made 75 cents an hour, right? Fighting COVID and cleaning feces off the wall and urine and blood, and this is my job, right?”

With little known about the virus at the time and his risk with asthma, Brown says he told supervisors he wouldn't come in every day, but he said they said doing so would result in a "1-15." Brown says he was soon scheduled to appear before the Board of Parole.

“I couldn’t survive that, so I had no choice but to do the work that they wanted me to do and continue to put my life on the line fighting COVID-19, even though I felt afraid for my own life,” he said.

A conversation with his wife, Jamilia Land, who now chairs the California Abolition Act Coalition, inspired him to make a change.

“She said, 'What can you make an appeal about not being able to work?' and I'm like, 'No.' She said, 'Well, just change the constitution!'" Brown recounted.

The California State Constitution was ratified in 1879. In the original document under Article 1 Sec. 18 it says: “Neither Slavery nor Involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crime, shall ever be tolerated in the State.”

Brown and Land contacted State Senator Sydney Kamlager after he wrote a proposal for the California Abolition Act in his cell. Kamlager is carrying it through the state legislature. It’s now formally known as Assembly Constitutional Amendment 3, or ACA3.

“ACA 3 is part of a national movement across the country of states working together to repeal these kinds of provisions,” Kamlager said.

California is among 20 states that still allow involuntary servitude on its books and is the latest trying to change it.

“We should not be saying it is okay to have slaves to have forced labor. We have a very dark history for many ethnic groups who've been subjected to involuntary servitude, and I just think it's time for us to stand up and say no,” Kamlager said.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, African Americans remain overrepresented in California’s prison population.

In 2017, the most recent year of data, 28.5% of the state’s male prisoners were African American, compared to just 5.6% of the state’s adult male residents.

According to a 2017 report by the Prison Policy Initiative, inmates earned between 8 and 37 cents per hour on average for regular prison jobs,

Brown says, when prisons prioritize cheap, forced labor over rehabilitation of inmates, communities of color, especially Black communities, are endlessly harmed if they can’t successfully re-enter society.

“It's not about stripping, you know, prisoners from the obligation of working, but more so along the lines of not filling the coffers of private prison corporations who place punitive labor, over those people dealing with their traumas,” Brown said.

The California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation (CDCR) declined to comment on ACA3.

While a legislative analysis of the bill doesn't have any opposing arguments on file, it notes CDCR is concerned billions in dollars of costs if they should be required to pay minimum wage. The analysis says these fiscal impacts are unknown without litigation.

ACA3 is up for a hearing before the State Senate on Tuesday. If passed, it would be placed on the ballot in 2022 for all California voters to approve or reject it.

WATCH ALSO:

ABC10: Watch, Download, Read