SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Seventy-eight years after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066, California has officially apologized for its role in the internment of 120,000 of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a day of remembrance on Wednesday for the Japanese-American internment, marking a historic moment for the state that imprisoned more American citizens than any other in the U.S.

At the time, famed photographer Dorthea Lange was granted access to the internment camps, making remarkable photos of Japanese Americans, both young and old, who were forced into racial relocation and concentration.

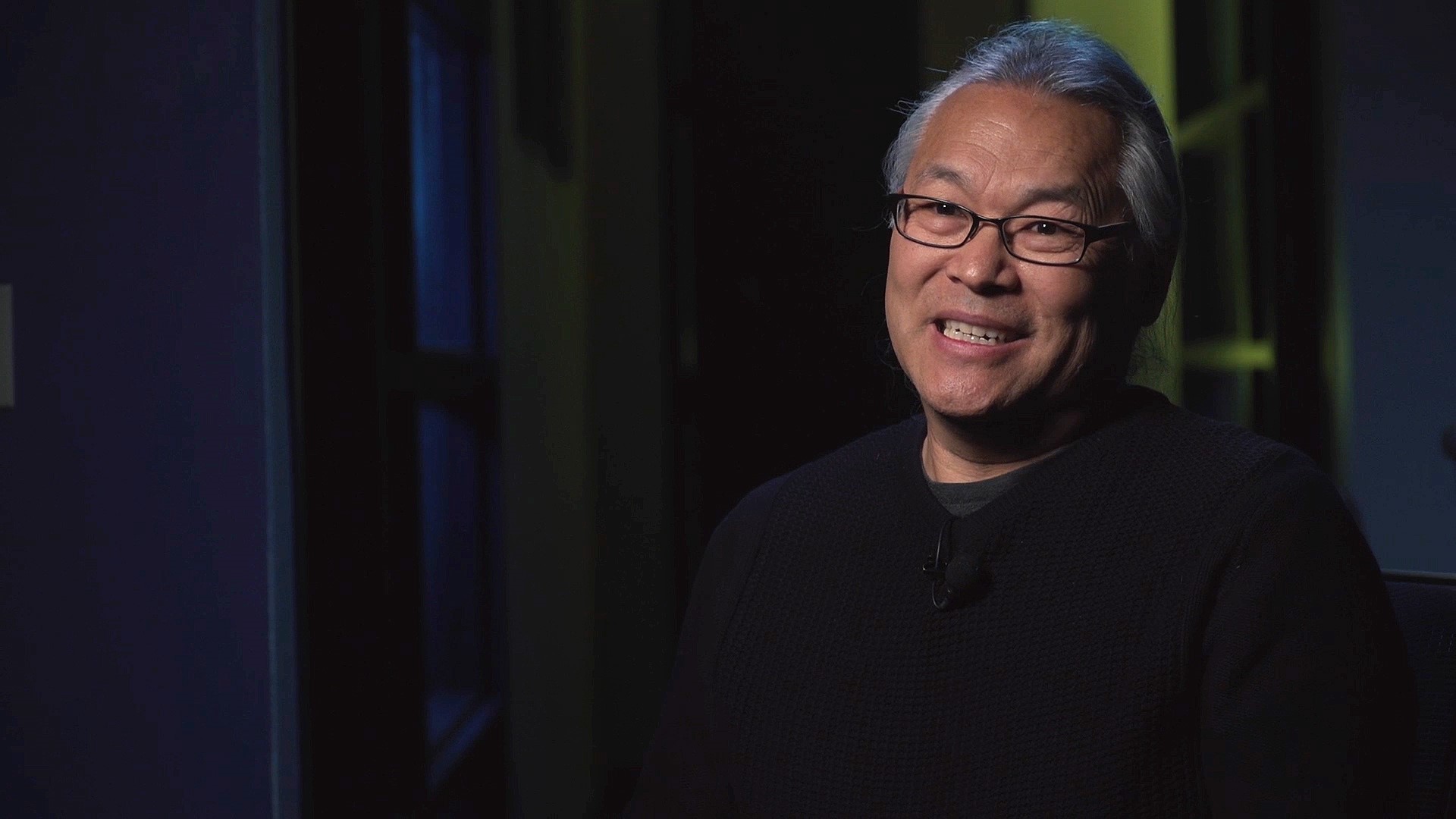

Over the years, Sacramento Bee Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Paul Kitagaki Jr., whose family was forced to relocate to an internment camp, has been photographing some of the original subjects — or their direct descendants — from Lange's photographs.

Kitagaki spoke to ABC10 on the 78th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 about his family, his journey through Lange's photography and what it means for the Japanese-American community for the state of California to apologize.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

ABC10: Can you put into perspective what this day means to you?

Kitagaki: The incredible thing about my family was that Dorothea Lange, the famous documentary photographer, photographed my family leaving Oakland. I didn't know about my story with my family, or that they were even incarcerated in World War II until I was a 16-year-old taking an American history class in 10th grade. I was shocked when I learned about it.

ABC10: How important is it that California officially apologized?

Kitagaki: I think it is very important for California to do a formal apology. The federal government did an apology in 1988 and that was so important for so many people I interviewed, to get an apology from the federal government because they were American citizens.

A lot of people here in California lost their jobs. A lot of the rhetoric from the media — Hearst and the McClatchy papers — tried to get rid of Japanese Americans during the war.

ABC10: It seems like those who were incarcerated did not want to talk about the internment camps.

Kitagaki: My family, my parents' generation, which was second-generation Japanese, they didn't talk about the story. It was something they wanted to get past. I think they felt shame and guilt. They were American citizens. They were locked up behind barbed wire, taken away from their home, put in these nasty places. They had to build their lives again.

Once they came out, they still had to face a lot of racism and prejudice when they came home. They didn't know what to expect, but I think they wanted to put on a cocoon on my generation. They wanted to shelter us from all that bad stuff that happened to their family, their parents.

I went to my parents to ask them about it, and they just said, 'Oh, well, we were put away into these camps, they were dusty, were cold and the food was bad.' They didn't talk about what was in their heart.

ABC10: Did your family have an understanding of how long they were going to stay in the internment camp?

Kitagaki: They had no idea what was going to happen. Everyone had two pieces of luggage to carry. You couldn't bring a radio or a camera. A lot of Japanese Americans burned their family photos because maybe they had a relative who was in the military in Japan, Japanese writings, they destroyed all that.

READ THE LATEST ON ABC10:

FOR NEWS IN YOUR COMMUNITY, DOWNLOAD THE ABC10 APP:

►Stay In the Know! Sign up now for ABC10's Daily Blend Newsletter