If you're viewing on the ABC10 App, tap here for multimedia.

The Carr Fire claimed the lives of two adults and two children who lived in its path despite evacuation orders and dozens of alerts issued by first responders as the flames roared through the neighborhoods West of Redding, California.

Two firefighters died fighting the Carr Fire, along with a utility worker killed in an accident during recovery efforts. But four of the seven people who lost their lives in this fire were killed in their own neighborhoods.

ABC10 has learned that dozens of electronic alerts were sent to the community, in addition to the hard work of rescuers on the ground to try to reach people and warn them in person.

It raises a difficult question: Were any of their deaths preventable?

IT BURNED FOR DAYS BEFORE TURNING DEADLY

The Carr Fire didn’t start out as the monster it eventually became.

In an area where people are used to living with fire, it was easy for people to shrug off at first. The fire burned for three whole days in a less populated area before it forced the mass evacuation of homes.

It started by Whiskeytown Lake, an area operated by the National Park Service about five miles to the West of Redding.

People in Shasta County started to receive alerts about the fire on Monday, July 23—the day the fire was accidentally sparked by a “recreational trailer malfunction,” according to park officials.

The next morning, fire commanders reported making “good progress” thanks to an “aggressive battle” overnight.

But the Carr Fire was stubborn. It kept growing, burning up more of the park as the week went on.

Fire crews tried to build lines around it, but the rough terrain made that work slow-going. Meantime, the fire was helped along by triple-digit temperatures and dry fuels.

It went on like that until Thursday, when the Carr Fire began to make its own weather.

It spawned what some meteorologists consider to be an honest-to-goodness tornado of fire, which quickly pushed flames out into that bone-dry fuel.

That allowed the Carr Fire to mushroom in size, shooting Eastward toward Redding, jumping the Sacramento River, and claiming more than a thousand homes.

A little before 10 o'clock Thursday night, we learned of the first confirmed death: Don Smith was an 81-year-old contract bulldozer operator who died while helping to build fire line in the North part of the town of Shasta.

He was “overtaken by the fire and was found deceased by emergency personnel,” according to the Shasta County Coroner.

HOW PEOPLE WERE WARNED

The warnings began Monday night after the fire started and escalated Thursday when rescuers scrambled to evacuate people from the neighborhoods between the park and Redding.

In the worst of it, first responders started going door-to-door to tell people they needed to evacuate— that method is relatively slow and risky compared to electronic warnings, but generally the most effective way to get people to comply with evacuation orders.

Electronic alerts have the advantage of reaching people more quickly. Dozens of alerts went out using different kinds of technology.

Shasta County did deploy the technology that went unused in the 2017 Sonoma County fires, drawing widespread criticism of the response from local officials there.

Shasta County’s dispatch agency confirmed to ABC10 that a total of three alerts were issued on a federally-regulated system called WEA, which stands for “Wireless Emergency Alerts.”

You likely recognize the technology if you’ve ever received an AMBER alert notice on your smartphone—an emergency alert sound plays and a message forces its way onto your screen.

Shasta County rescuers used one more system that was not activated in Sonoma’s 2017 fires: the Emergency Alert System (EAS.)

TV and radio stations in Redding blasted out EAS warnings about the Carr Fire. State officials reported that this technology that went unused in Sonoma because the broadcast stations for the area also reach the entire San Francisco Bay Area and the so-called “warning spillover” would have alerted millions to an emergency that was no threat to them.

EAS and WEA alerts reach people whether they’ve signed up or not, but Shasta County also operates a warning system of its own that people can subscribe to through a contract service called “CodeRED.”

Previously dedicated to robocalls of landlines, the county upgraded the service this January to allow people to get the alerts via cell phone.

Dispatchers told ABC10 that the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office and Redding Police Department issued a total of 59 different notifications about the Carr Fire on CodeRED.

Those alerts were sent to 31,979 registered phones in the form of calls, text messages, and emails.

30 of the 59 alerts for the Carr Fire went out between Thursday morning and Friday morning, while the evacuation orders kept coming.

TECHNOLOGY HAS LIMITS

The WEA system that pushes alerts to cell phones is a heavy-handed tool, which is why it’s only used in extreme cases.

On the positive side, you don’t have to sign up for it. It’s an opt-out system.

If a cell phone tower is ordered to issue a WEA alert and your phone is in contact with that tower, you will get that alert—regardless of where you are.

That can lead to confusion. If you want to warn people on one side of a hill about a fire, but the cell phone tower is on top of that hill—the message is going to reach people on all sides of it—even those who don’t need to evacuate.

This means that the WEA messages have to be clear and precise to avoid causing confusion and clogging up evacuation routes with people who don’t need to leave.

Unfortunately, the WEA system isn’t built for detailed messages.

Messages are currently limited to 90 characters—less than a third of the maximum length of a tweet.

The FCC has made rule changes aimed at allowing longer messages and more precise geographic targeting of WEA alerts, but those rules aren’t supposed to take effect until next year.

By contrast, the CodeRED alerts are less regulated because they comes from an opt-in system. But that’s a drawback because you have to sign up in advance of the emergency, making it unlikely to reach everyone who could use life-saving information. Visitors are unlikely to have registered in advance with a county they are headed to for a vacation.

Both technologies are only as good as your cell phone connection, which can be spotty in remote and mountainous terrain like the Carr Fire area.

QUESTIONS REMAIN

We don’t yet know what, if any, alerts were received by the two adults and two children who lost their lives in the fire.

The family of 62-year-old Daniel Bush believe he might not have died if he’d had help evacuation. His sister Kathi Gaston told the Redding Record-Searchlight that she was upset about roadblocks keeping her from coming to his aid:

“If we’d been able to go in when we wanted to, he’d be alive right now,” she said. “I’m very upset about it.”

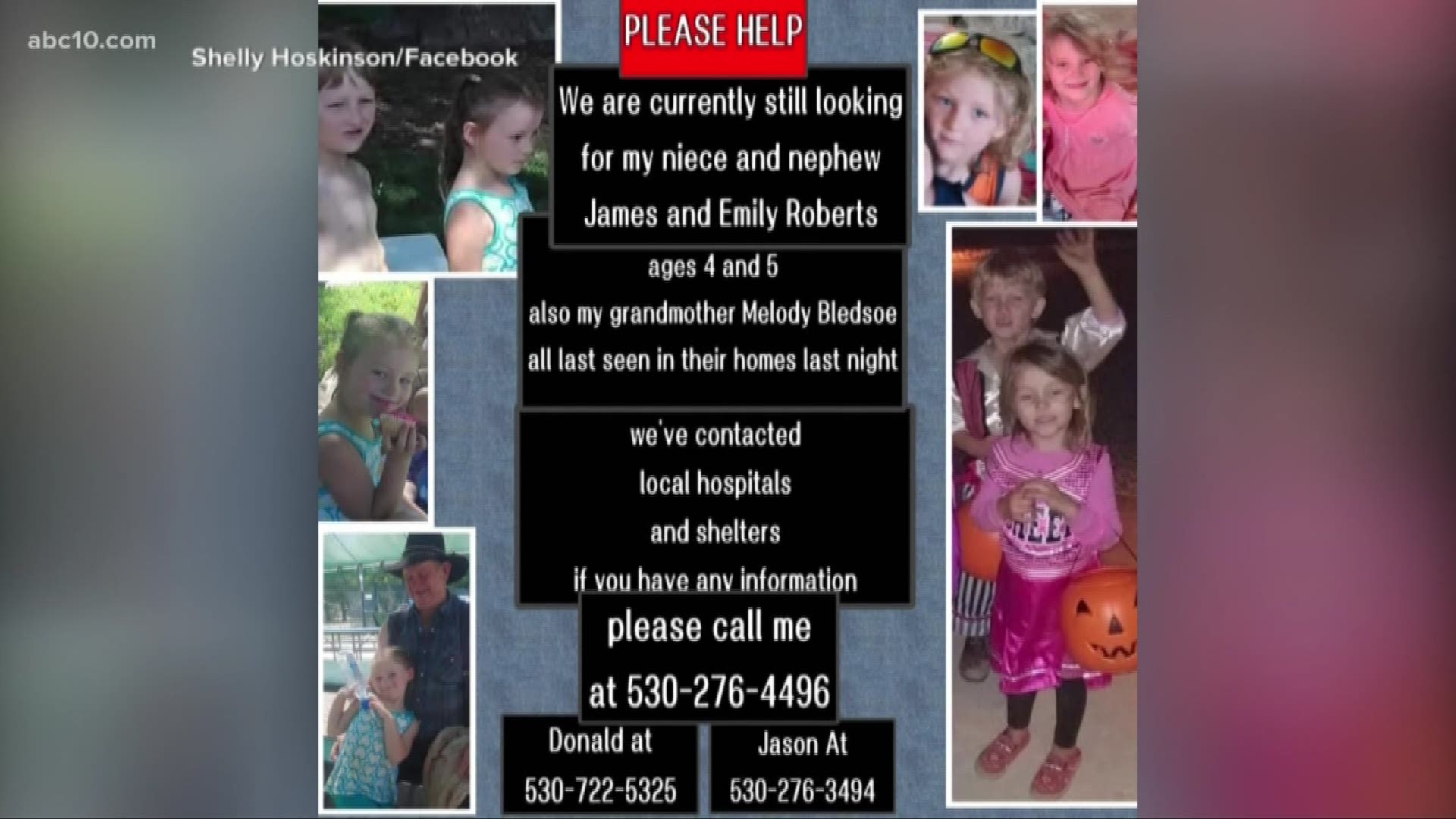

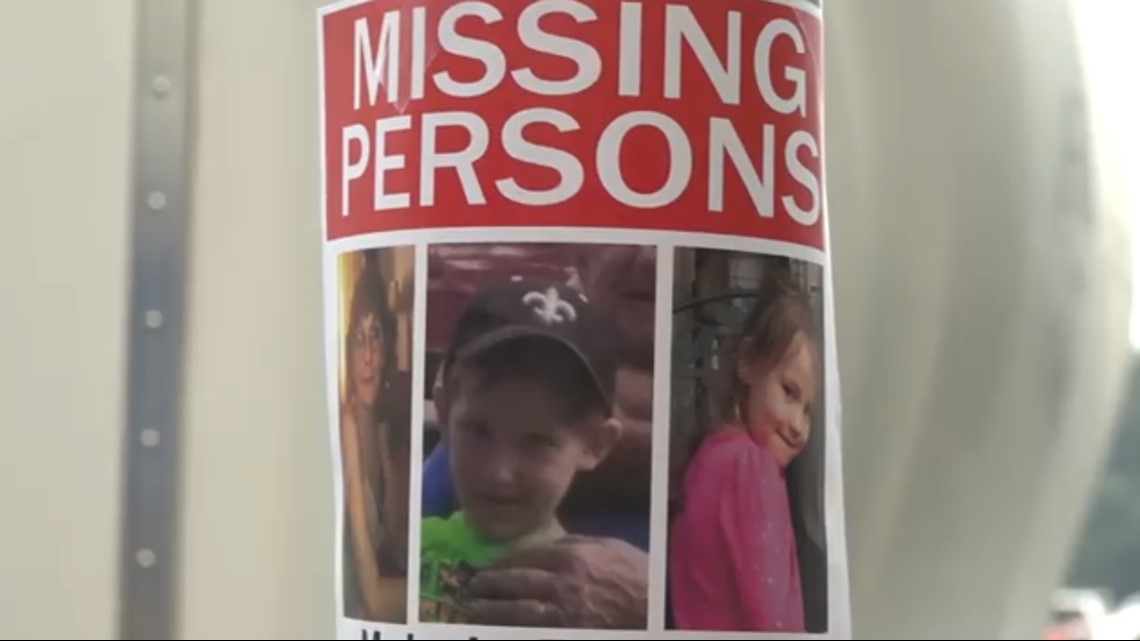

70-year-old Melody Bledsoe died in her mobile home along with her great-grandkids James Roberts, 5 and Emily Roberts, 4.

They spent their final moments on the phone with Melody’s husband Ed Bledsoe, who attributed their deaths to the quickness of the fire. He’d driven to town for an errand and was only gone a matter of minutes when he learned the fire had made a run for his house.

Investigators will also look for lessons that can be learned from the deaths of the people who were working on the Carr Fire.

In addition to bulldozer operator Don Smith, the fire killed a Redding city firefighter named Jeremy Stoke.

Jairus Ayeta, an 21-year-old lineman apprentice for PG&E, died in an accident days after the other fatalities.

You can contact ABC10 reporter Brandon Rittiman with tips about this or any story: brittiman@abc10.com