SACRAMENTO, Calif. — This Black History Month, ABC10 is highlighting the contributions of African Americans in the arts in honor of the 2024 Black History Month theme.

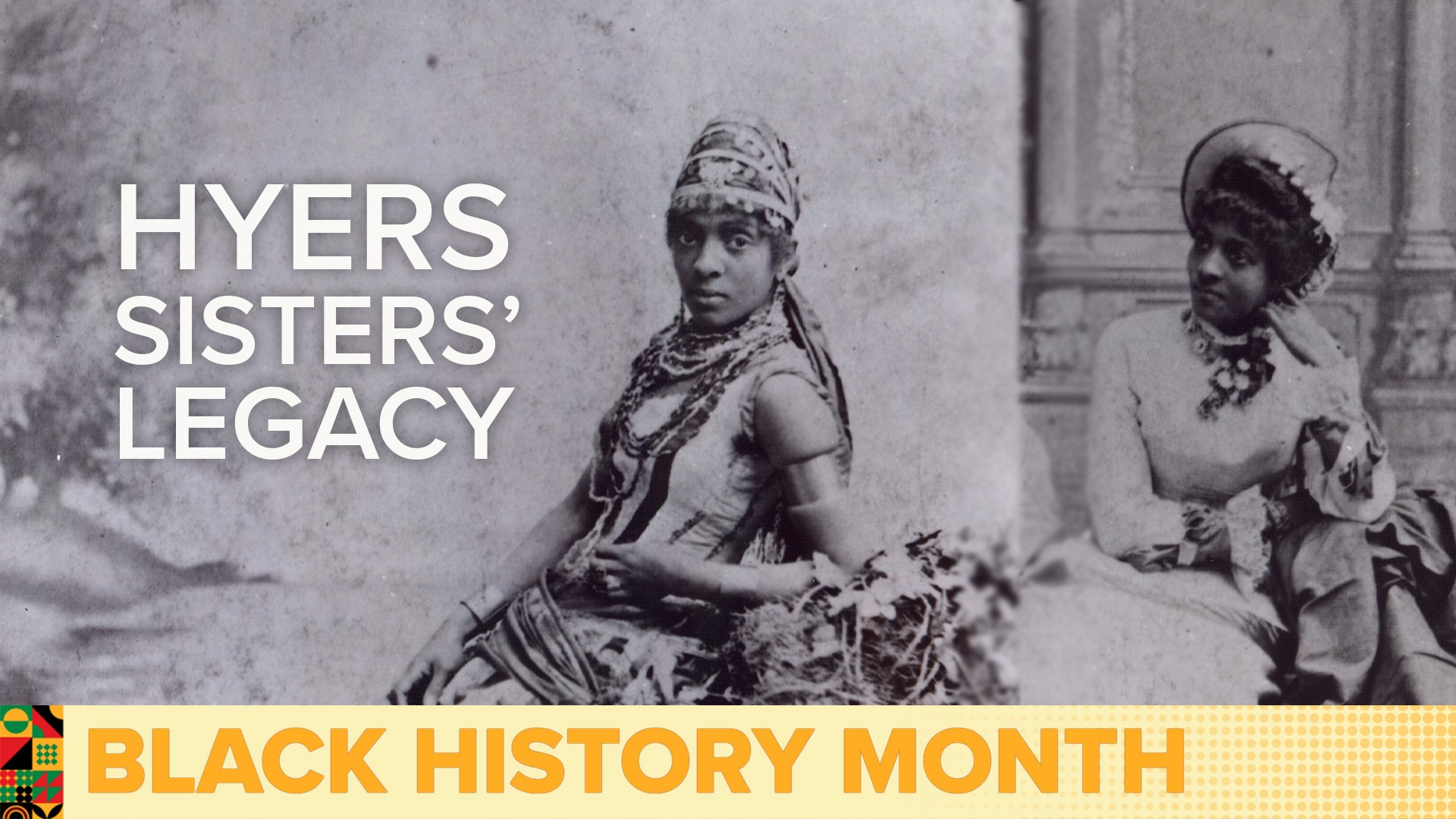

Two trailblazing sisters who helped pioneer modern American musical theater were from Sacramento.

Anna and Emma Hyers changed the course of popular entertainment from a form that ridiculed African Americans to one portraying them with dignity.

Their story is told in two award-winning documentary films produced by Susheel Bibbs, a classical singer, documentary filmmaker and researcher, who lives in Sacramento.

Through Bibbs’ research for another documentary on Mary Ellen Pleasant - known as the Mother of Civil Rights in California - Bibbs learned about the contributions of a largely unsung pair of sisters who changed the face of musical theater in more ways than one.

“We owe [the Hyers Sisters] the concept of human-ness of African Americans and trying to portray that [on stage],” Bibbs said.

Anna and Emma Hyers grew up in Sacramento in the 1860s. They performed opera with their parents from a young age.

“The father and mother were amateur opera singers,” Bibbs said.

Bibbs says the Hyers Sisters eventually embarked on an opera career as a duo becoming the very first African American women to entertain white audiences while touring across the U.S., garnering acclaim in the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era.

“They were so popular that when they got to New York, they had the distinction of becoming the first African American women to be on a mixed stage in a mainstream – white, Caucasian – audience,” Bibbs said.

This was no small accomplishment, especially against the backdrop of another type of performance popular at the time, known as minstrel shows.

Minstrel shows got their start in the 1830s and 40s. White actors donned “blackface,” painting their face with burnt cork and portraying offensive caricatures of African Americans.

Bibbs shows the offensive images of minstrel shows in her documentaries. ABC10 chose to show selective clips in our story after consulting with Bibbs, who said she believes it’s important to show them because “if you don’t see the imagery, you don’t understand what the Hyers Sisters were up against and fighting for.”

“It's making fun of the way people talked, also,” Bibbs said.

As she and retired public historian Dr. Rick Moss explain, these insulting performances were vile attempts at giving white audiences justification for slavery before and during the Civil War, portraying the false narrative Black people were ignorant and inferior. The depictions got worse.

“After the Civil War, it became angry. Then it became something biting and harsh,” Bibbs said.

In the decades after the war, minstrel shows grew in popularity among white audiences as more African Americans - especially formerly enslaved people - gained access to education, wealth, land, and political power.

Bibbs points out these biting depictions had long-lasting harm, influencing culture, people, and eventually, racist policies, such as the 'Separate but Equal' doctrine and Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation well into the 20th century, the effects of which still impact Black Americans to this day. Even the name Jim Crow itself would come out of minstrels as it was the name of a staple character created by Thomas Dartmouth Rice, known as the Father of Minstrelsy.

“Even though the proponents of slavery lost, their belief in the inferiority of Black people did not disappear,” said Moss.

He is the former Chief Curator and Director of African American Museum and Library at Oakland and provides an important historical perspective. He says minstrel shows were so popular and lucrative after the Civil War, that some African Americans formed their own minstrel troupes and performed in blackface, using burnt cork just like white minstrel performers.

“On the part of those performers, they had to make a living. They had to live and they had to eat. Would it be easier digging a ditch? Or going on stage and performing and being something that you know you're not?” Moss said. “So it was survival, I believe.”

But out of that also came prominent Black performers such as Bert Williams who, unlike many other blackface performers, used the stage to present African American characters and stories with dignity. While putting on blackface makeup just like his white counterparts, he did not perform for humor at the expense of African Americans.

"His characters were not... the same jolly, ignorant characters of prior minstrel show(s). It had some heaviness to it, there was a bottom to his performances. And audiences, Black and white, got it, and they understood that he was much more than just what they saw on stage. There was more behind this person," Moss said.

Showcasing performances portraying the African American experience with dignity and humanity was what the Hyers Sisters did next instead of pursuing an international opera career.

“The Hyers, in 1876, decided they weren't going to Europe; they were going to abandon a dream for the greater good,” Bibbs said. “And they were taught that it had to do with their people being free - and free of the bondage of the imagery that the blackface minstrels put upon them.”

Seeing the growing hostilities against African Americans, the Hyers Sisters started their own touring theater company called the “The Hyers Comic Opera Company.”

“They were the ones responsible for the first American musical. Not the first African American musical; the first American musical,” Bibbs said.

They produced several musicals and toured for some 20 years — all without the use of blackface.

“They focus these stories on the African American experience, from slavery to freedom… to see African Americans as human beings,” Bibbs said. “They had white and Black in the cast. They had dancers and nobody had blackface, and so you're looking at something really revolutionary.”

The work of the Hyers Sisters and other pioneering Black artists helped lead to an end of minstrel shows, according to Bibbs and Moss.

“Something else came along to replace it, and Black people had a large hand in making sure there was something much better that could replace it,” Moss said. “Those little battles being fought - whether to cork or not cork, play the banjo or not - it's a pretty rich legacy.”

This rich legacy lives on in Bibbs’ own personal story, who pivoted from a career in classical music to telling the stories of Black women trailblazers through documentary filmmaking.

“It was really something to make that change and go against what people expected of me,” she said. “That’s what the Hyers did: they connected with that, in me, that ability to connect your dreams with your values.”

ABC10 had many internal discussions and collaborated with African American community members and colleagues about how to use and talk about the racist images of minstrel shows in a responsible way – and only to educate and tell this important story. Everyone we spoke with emphasized the importance of showing the images, to acknowledge America’s dark past and fully understand the African American experience – while also celebrating the resilience of the Black community, as clearly demonstrated by the efforts of the Hyers Sisters.

Anyone interested in watching one of Bibbs’ documentaries on the Hyers Sisters can rent or purchase it HERE. Actors featured in Bibbs' film include Hope Briggs, Shawnette Sulker, Robert Sims, Omari Tau, Othello Jefferson and Bibbs herself.

WATCH MORE ON ABC10: Honoring Black history at the Sojourner Truth African Heritage Museum in Sacramento