MODESTO, Calif. — The end of Modesto's tent city will mean ending a burst of momentum that saw families put in homes, thousands of services given out, and even a reduction in crime. Despite the highlights, officials say the outdoor shelter can't be the only option, and that the next step has to be taken.

At the beginning of 2019, Modesto and Stanislaus County officials allowed hundreds of homeless people to camp under the 9th Street Bridge while they tried to find an answer to the city's homelessness problem.

It was a quick and unprecedented reaction brought about by a 9th Circuit Court ruling, which generally prevented agencies from enforcing certain laws on the homeless when there weren't enough shelter beds to accommodate them.

At first, the city allowed the homeless to camp out in Beard Brook Park in 2018, so they could enforce the no camping ordinances in the rest of the city parks.

RELATED:

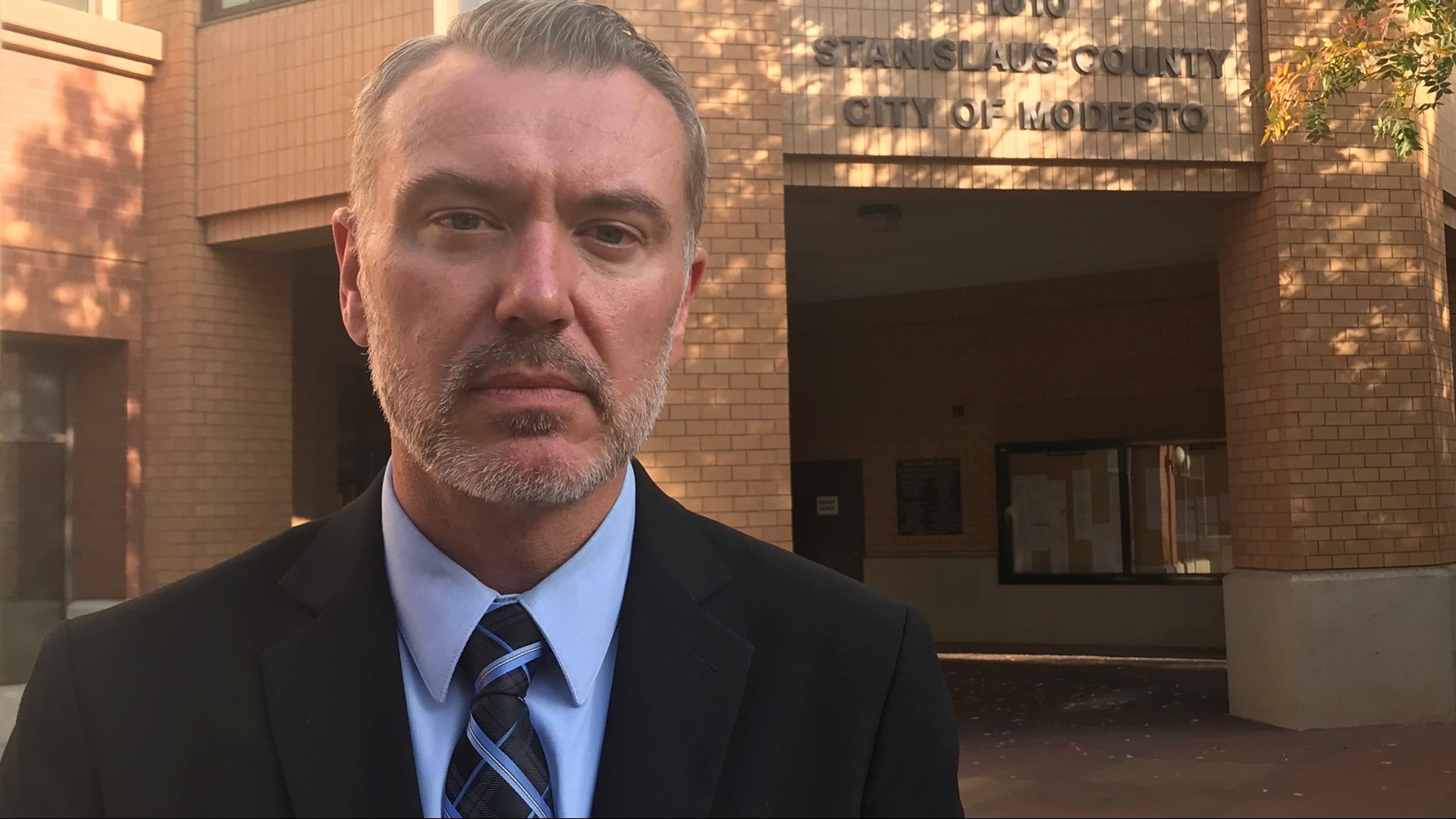

“Beard Brook Park was an emergency situation," said Modesto spokesperson Thomas Reeves. "When our leadership at the city got together and decided that we needed to open up the park, we opened Beard Brook Park not knowing what to fully expect but we knew we had to do something fast."

With the rains coming at the end of that year, the lack of level ground, and mud sliding from the hill, the park simply wasn't safe, and a new site under the 9th Street Bridge was made.

The area had lines of uniform tents that housed about 700 people over the course of the Modesto Outdoor Emergency Shelter's (MOES) lifespan.

In that time, Stanislaus County provided 3,100 services and transitioned 25 families to homes. Many of those services dealt with case management, homeless court, substance abuse, youth services, and mental health.

According to Reeves, Modesto even saw a crime reduction, specifically with calls for service from police and ambulances.

"We’ve seen a direct correlation between allowing for our homeless individuals to go into one location and the calls for service and the quality of life crimes that we would otherwise experience in other parts of the city go down," said Reeves.

Amid all the success and positive attention the MOES has gotten, it will ultimately be shut down and its residents will have to find new shelter. City officials have already committed to returning the park back to the public.

While it seemingly derails the momentum that the MOES was generating, Reeves says that, despite the benefits the city saw, the MOES wasn't doing anything to solve homelessness.

"Where there might be significant benefit in opening or allowing for unlawful camping at this one facility, the reality is that there is much more that needs to be done to break the cycle of homelessness...," said Reeves.

He added, “There’s other housing needs that we have in town that we’re solving, so we have to be able to say 'this is not the only answer.' There are other issues that we need to solve and that we’re working toward solving.”

According to Becky Meredith, deputy executive officer for Stanislaus County, MOES wasn't even really a shelter. She says it's more campground than shelter, and, by HUD guidelines, the people there are still considered unsheltered.

"MOES was, generally speaking, an unregulated outdoor camping area," said Meredith. "Law enforcement did not search tents for drugs."

"In the [new] shelter, weapons, drugs, and alcohol are not allowed," she added. "Those would probably be the biggest things folks were allowed to do and have at MOES that will not be allowed here [at the Salvation Army shelter].”

Once the MOES closes, it will take eight weeks to perform "bio-hazard remediation."

"There’s still going to be substantial waste, human waste, possession waste, the tents are likely going to need to be disposed of," Meredith said. "We don’t anticipate any of the tents are going to be reusable. There’s a lot of drug paraphernalia that is on the ground still out there because again this is unsheltered camping.”

The closure of MOES is intended to coincide with the opening of the new 182-bed shelter run by the Salvation Army. However, Maj. Harold Laubach of the Salvation Army knows that the traditional shelter life can be a tough adjustment.

“Not everyone is comfortable living that close to someone else, so, if you’re dealing with people with mental health issues, you’re dealing with people with anti-society issues, and things like that... it's going to be much more comfortable to live in a tent outside where you don’t have to deal with other people," Laubach said.

The shelter tries to make up that difference by having personal relationships and a reputation with the people they take in.

“We understand not everybody is capable or willing to move to a shelter," Laubach said. "We make it safe as possible. We make it as welcome and as open as possible, and those that choose to take it can [do so] and those that choose other arrangements, that is up to them.”

With the closure of MOES pending, the city of Modesto is also expecting a possible increase in homeless-related issues and illegal camping in the downtown area. If those issues happen and people refuse help, the city is prepared to enforce its laws and regulations to combat what Reeves called the "negative impacts of vagrancy."

"We’ve been making it very clear since the beginning of this issue over a year ago.. we are not going to criminalize homelessness, but there will be accountability for the negative impacts of vagrancy-related issues in town.”

FREE ABC10 APP:

►Stay In the Know! Sign up now for ABC10's Daily Blend Newsletter

WATCH ALSO: