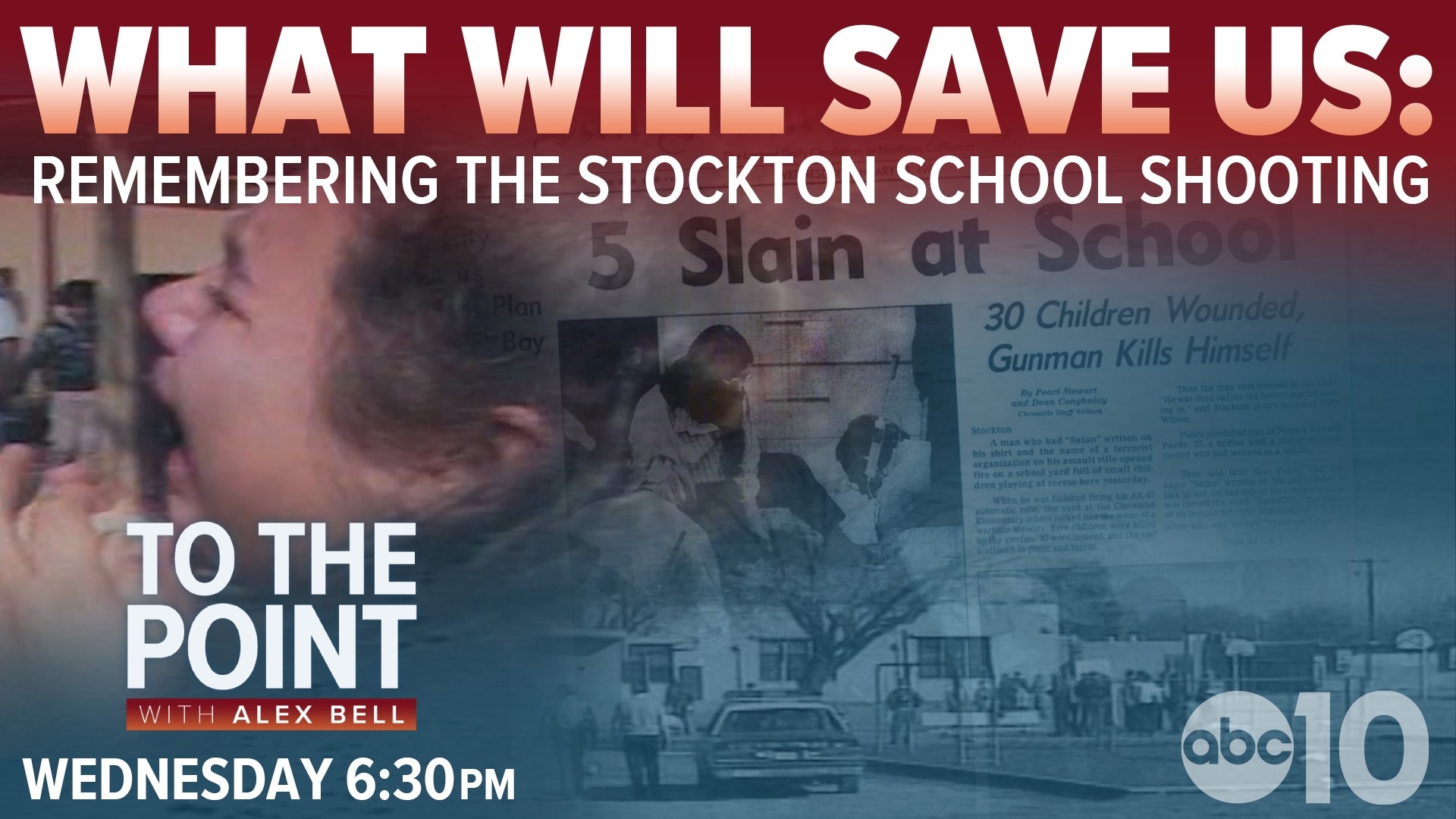

What Will Save Us? | Remembering Stockton's Cleveland Elementary School shooting

Survivors of the shooting are revisiting the school together for the first time and sharing how the shooting led them to lifelong advocacy

Five students were shot and killed at Stockton's Cleveland Elementary School on Jan. 17, 1989. It was one of the nation's worst school shootings at the time.

Many people thought they would never see a school shooting like it again, but it's unfortunately a relived reality. Survivors of the shooting are revisiting the school together for the first time and sharing how the shooting led them to lifelong advocacy. Here are their stories.

Chapter 1 THE DAY OF THE SHOOTING

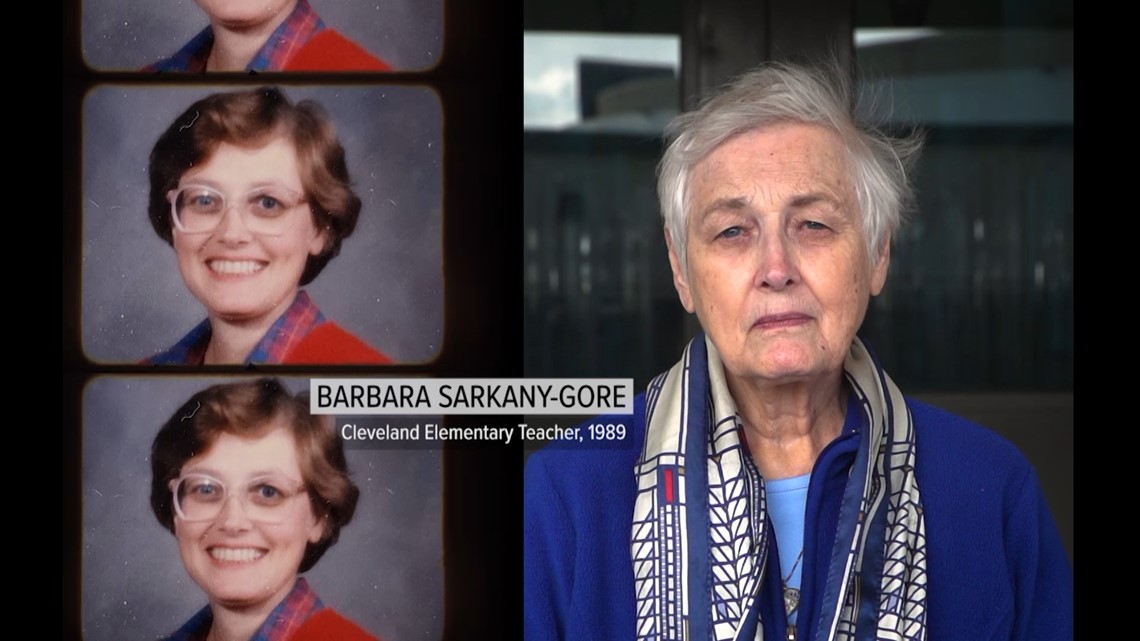

Barbara Sarkany-Gore was a kindergarten teacher at Cleveland Elementary School in 1989.

“I had just stepped back to view my work when the bullets came to the wall and landed at my feet, at which point I yelled to my morning teacher to run," she said.

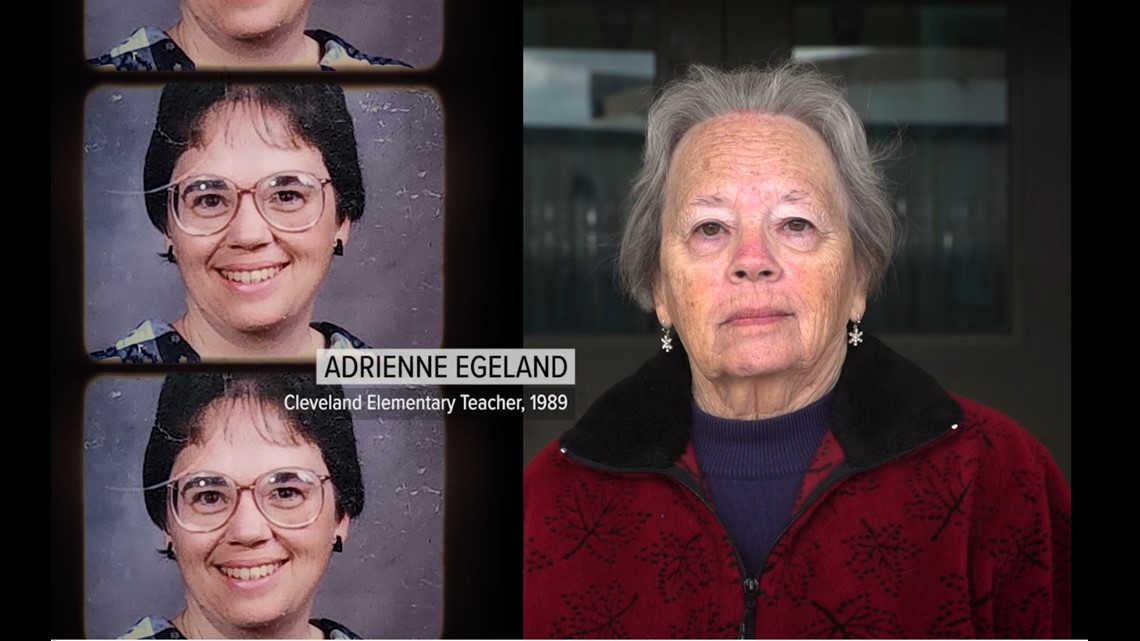

Fellow colleague Adrienne Egeland was also a kindergarten teacher. She thought she heard firecrackers before realizing moments later it was the sound of gunfire.

“We opened the doors and there were kids coming through the hallway right outside our room and they were racing. Some of the kids would get partway into the hallway and fall because they had been shot," said Egeland.

A gunman set his car on fire with a Molotov cocktail during recess. He then walked onto the elementary school campus where 300 first, second and third-graders were playing. He fired more than 100 rounds with an assault rifle in less than a minute.

“I had been trained, very seriously trained in first aid in basic training, but we had no supplies. There was nothing to stop the bleeding with except our hands,” said Egeland.

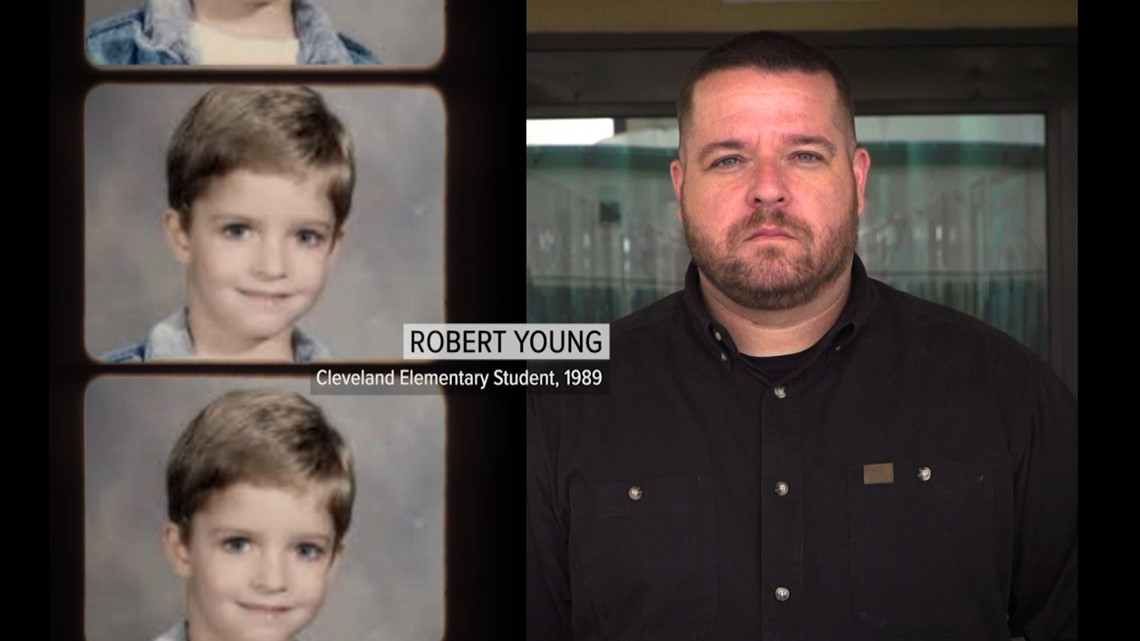

Rob Young was 6-years-old at the time of the shooting. He says his mom would walk him to school.

“She walked me up to the back gate. At the time it was just an open gate of just a pole and a pole. She gave me a hug and a kiss on my cheek and told me, 'Have a good day.'"

Unbeknownst to him, it would be the same gate the gunman walked through. Gunfire erupted while he was on the playground.

“I knew everybody was running and screaming and that alone was terrifying for me,” said Young.

He started running to his classroom when he was shot.

“I turned to see where my best friend Scotty was and when I turned around, that's when I got hit. That's when the round went through my right foot. I landed on the ground and another round struck me in my chest, too. It hit the pavement right before it went into my chest," said Young.

When he looked up from the pavement, he could see his substitute teacher holding a classroom door open.

“I took off running. Bullets were coming through the wall and she was just telling us to get down under our desks," said Young.

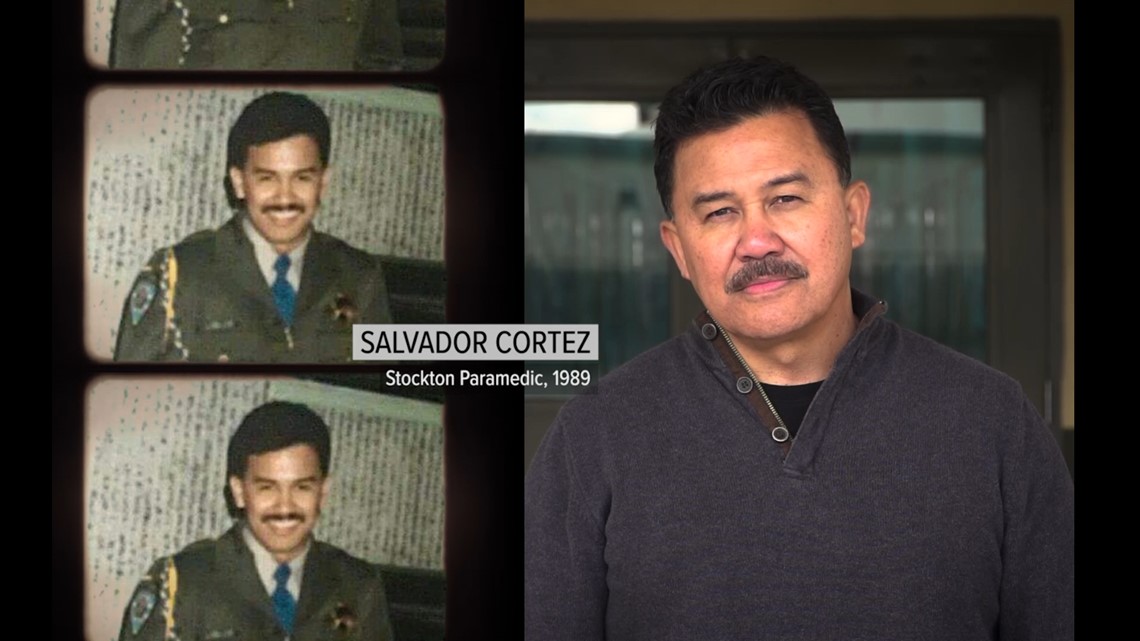

Salvador Cortez was finishing up the last month of his paramedic ambulance career when a call for a man with a gun came in at Cleveland Elementary.

“We didn't have a protocol for active shooter response. In fact, the term had not even been coined yet (active shooter),” said Cortez. “As we started walking out some of the hallways, you could see the blood trails of the kids who had been shot and it would lead to a cupboard. Then we would open the cupboard and there would be a child there."

The shooter was 24-year-old Patrick Purdy, a former student of Cleveland Elementary. Purdy shot himself and died at the scene.

“What I realized is that the scene was so disorganized and so chaotic that none of the systems that are in place today were in place that day [in] 1989. We didn't have kind of an incident command system structure,” said Cortez.

Since Rob was in first grade, the only thing he knew about gunshot victims was what he'd seen in the movies.

“You get shot, you die," said Young. "The thing that went through my mind? I can't die right now because my mom's not here, my family's not here with me.”

Five students all under the age of 10 died that day. More than 30 others were injured. At the time, an overwhelming majority of the student population was Southeast Asian.

"Those families, you know, a lot of them had escaped the Killing Fields of Cambodia, Khmer Rouge and Vietnam. They came here as refugees to escape what was going on in their home countries and they come here to be safe,” said Young.

Chapter 2 THE NEXT DAY

Some students and teachers returned to school the following day.

“I was in disbelief, because who would shoot children? And why?” said Sarkany-Gore.

She says returning the next day was almost as bad as the day of the shooting. She felt overwhelmed and unsafe.

“I wanted to be with my colleagues, someone else, other people [who] had been through the same thing... but I didn't want any children in my room," she said.

Staff would continue to find bullet shells in supply cupboards well into the school year.

The shooting changed the little moments Egeland shared with her students.

“I never pulled one of my students aside to talk to them about their behavior when it was time for them to go out for recess or to go to lunch or to go home for the day. I never wanted a harsh word or a message to be part of them leaving me; the last thing they would remember," she said.

PTSD is something the two teachers live with today.

"I do have PTSD and panic disorder, and I do take medication,” said Sarkany-Gore. “It's something that I've learned to live with. It's never going to go away. Sometimes it feels like it was yesterday, and other times it feels like in some other life.”

For Egeland, each time she hears about another mass shooting it impacts her more and more.

“How frustrating is it that 34 years later these incidents are still happening,” she said.

For Rob, the shooting robbed him of the innocence of being an invincible little kid. He soon realized many of his friends were killed that day or sustained significant injuries. The injuries he sustained are something he still lives with.

"It (the bullet) narrowly missed my heart and lungs. They're still there," he said.

The bullet that went through his foot left him with nerve damage and he had to learn how to walk again.

Surviving the shooting is one thing, living with the trauma decades later is another, but these survivors turned a painful tragedy into action.

Chapter 3 LIFE AFTER THE SHOOTING

State assembly members passed the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989 after the shooting. The California assault weapons ban was a first in the nation legislative restriction on assault weapons and served as a model for the U.S. assault weapons ban passed by congress in 1994. The federal law expired in 2004.

California's assault weapons ban remains uncertain today.

“A big focus of my life since the shooting has been trying to get people to understand why we are so determined to reduce the incidences like this,” said Egeland.

She and Barbara are members of the nonprofit Cleveland School Remembers. The organization promotes gun safety and advocates for legislation.

"It makes me feel very angry. It makes me feel like giving up. What does it take to have some kind of better gun laws?” said Sarkany-Gore.

Rob dedicated the last 20 years of his career to law enforcement, beginning his career as a Stockton Unified School District police officer.

“I was always proud to come back and really serve in that capacity. Everybody always asked, 'Did the shooting really push you towards that career choice?' And I would say it definitely strengthened it. I am a product of this district. I am a product of this school. I am a product of this community,” he said.

Salvador Cortez spent more than 30 years with California Highway Patrol before starting his own company, TacMed Services. He now teaches tactical medicine and active shooter training.

He says it gives him hope when he sees people take a class because he wants everyone to be safe.

"So much of the training that occurs today is lecture-based and so that makes it very difficult for an officer to actually understand what the feel of an active shooter event is. My course is scenario-based,” said Cortez.

A large part of the survivors' stories is making sure nobody forgets the young lives taken that day.

"I've always been afraid that if we stopped talking about it that my friends who were killed... that we're going to forget their memory. I don't want to let that happen. Their lives mattered,” said Young.

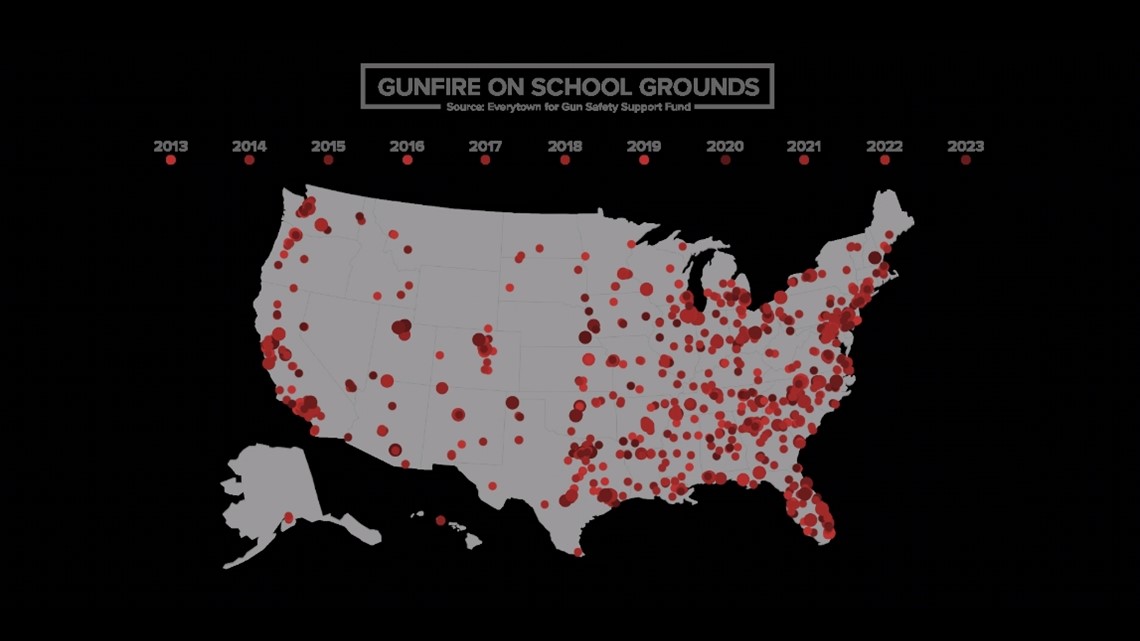

The organization Everytown for Gun Safety tracks school shootings. In the last 10 years there have been at least 1,092 incidents of gunfire on school grounds across the country.

More than 360 people have died and more than 770 have been hurt. Firearms are the leading cause of death for children and teens, according to the CDC.

Chapter 4 NEW GENERATION OF SCHOOL SAFETY

School campuses like Cleveland Elementary have been the backdrop of horrific scenes of gun violence for the last three decades. Day after day, devastated families and communities are grieving and trying to build a safer future. It’s changing the way schools are run and built.

Take Kairos Public Schools [in Vacaville], for example. They recently built a brand-new school and say they aren’t taking any chances.

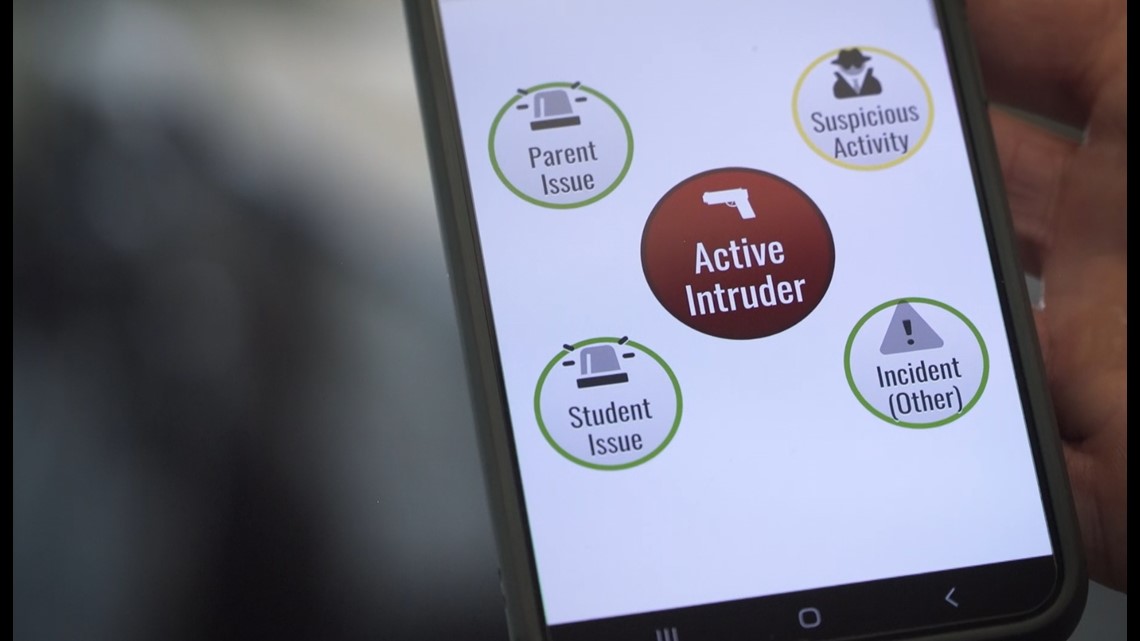

When you first enter the parking lot of Kairos Public Schools, they have cameras with license plate readers capturing everyone who comes onto the campus. Their cameras also use AI, facial and license plate recognition. They can set the school on lockdown with just the push of a button.

"On our phones we can push 'active shooter' and it's going to send an alert to every single person on the phone, as well as our intercom system. Then that sends law enforcement immediately coming into our direction," said Kairos Public Schools co-founder Jared Austin.

In the event of a lockdown, one button can also deactivate everyone's key card in the event someone harms a staff member and tries to access their card.

Leslie Shebley, a fellow co-founder of Kairos Public Schools, believes security is a primary focus. For her, one of the main features to help Kairos are panic buttons located in multiple locations throughout the building.

"So if there's ever an issue in any one workshop space, all they have to do is lift this up and hit the button. It locks the facility down and begins to notify the police,” said Shebley.

Every classroom also has an intercom system which gives vocal, audio and text instructions on what to do during a lockdown so staff and students have step-by-step instructions during a potentially high-stress situation.

The mass shooting at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas, happened as Kairos Public Schools was breaking ground on its newest school. Austin says it changed everything and the charter school began rethinking every detail of campus security.

He believes school safety must be a priority in any school design and will only continue to enhance in the future.

“We may never know if any of these measures were worth it, but we also may never know how many potential acts of violence they deter because of the steps we were willing to take and the investment we're willing to make," said Austin.