SACRAMENTO, Calif —

In 2015, Eduardo began the process of fleeing his home in Mexico.

He was forced to leave after his family got caught up with a powerful criminal organization. Eduardo knew too much about their activities, so they targeted him and his family.

“The torture was too strong,” Eduardo said. “They ripped part of my leg, they almost wanted to tear my whole leg off. I have scars. They broke a tooth and fractured my forehead. I thought if I left my state in Mexico, I would be safe. But no.”

Eduardo and his brother attempted to escape, but members of the crime organization caught up with them and killed his brother, who was only trying to defend Eduardo. The threats continued no matter where in Mexico Eduardo tried to hide, so he chose to leave.

When he made it to the San Ysidro crossing in Tijuana, he was met with thousands of Central American migrants arriving at the same time, attempting to claim asylum. Eduardo started volunteering, as he waited for his turn in the unofficial lists that placed people in line to request asylum at the Port of Entry.

“Eduardo was just this incredible force in the office,” said Rachel Antony-Levine, a volunteer at Al Otro Lado, a legal clinic helping asylum seekers on the Tijuana side of the border. “He would help out when migrants came in who were very vulnerable, who needed water and food before they could even start talking about their legal needs. He would tend to them with so much compassion and so much so so much warmth and really make them feel comfortable.”

When the time came, Eduardo crossed into the United States. Antony-Levine gave him her phone number, address, and the promise she would sponsor him to make it easier for him to be released by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE] on parole.

“Asylum seekers who have committed no crime, who have presented themselves at the Port of Entry are still getting detained and they have to get parole in order to get out,” Antony-Levine said, adding if the migrant doesn’t have a U.S. citizen willing to vouch for them, provide housing and, “basically take on their parole case, they don’t have a chance of getting out.”

Antony-Levine submitted an 86-page parole request which included letters from congressional offices. Eduardo, however, was still denied.

In a 2017 class action lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security, the ACLU and other groups claimed that under the Trump Administration, ICE field offices denied parole to almost 100 percent of detainees who were eligible for it. According to California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, “more immigrants are being held in detention facilities than ever before in American history.”

“People in immigration detention are civil detainees,” Aaron Fischer, Litigation Counsel for Disability Rights California, said. “What that means is that they are not charged related to any criminal conviction or sentence. They are there solely for civil proceedings, in this case, immigration proceedings.”

In 2016, the number of immigration detainees convicted of a crime was less than half, according to internal ICE documents reviewed by Mother Jones. Fischer added migrants are not there for punishment and many people in immigration detention centers are not required to be detained.

“The Constitution says that they should not be treated in a punitive type atmosphere,” Fischer said. “They are there merely to go through their immigration civil proceedings.”

In March 2019, Disability Rights California released a report about conditions at the Adelanto ICE detention center, the largest in California which houses about 2,000 detainees. The report notes a “significant number of people in detention are asylum seekers fleeing persecution and violence [and] can carry with them trauma.”

“They are extremely vulnerable to further deterioration and in many cases, they reach a breaking point where they engage in self-harm or even attempt to kill themselves,” Fischer said.

According to the Disability Rights California report, they often face counter-therapeutic treatment in detention centers.

Pilar Gonzalez, supervising attorney at Disability Rights, said prior to 2017, there were federal guidelines that allowed for people with disabilities, mental health needs, and medical needs to not be detained.

“That is no longer the case under President Trump’s immigration policies,” Gonzalez said.

RELATED:

Recent reports by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra and State Auditor Elaine Howle found that cities and counties in California that contract with ICE to hold immigration detainees, “lack proper oversight of these facilities, risking the health, safety, and rights of detainees.” Their findings included prolonged periods of confinement without breaks, lack of access to legal counsel, and poor communication with family outside.

“This negatively impacts their chances of getting asylum," said Christina Mansfield, co-founder of Freedom for Immigrants, a nonprofit that works to abolish immigration detention.

Part of what Manfield’s organization does is put together a network of volunteers who visit detainees in detention centers. Some volunteers even offer to host detainees for months at a time in their homes.

“There are many asylum seekers who are in immigration detention for no other reason than they do not have a place where they go after they are released,” Manfield said. “And so the government will not release them.”

Maya and Miles Harris are hosts, currently housing two sisters seeking asylum from Honduras in their East Sacramento home.

“There’s really not a more concrete thing you can do than giving a person who needs space, space… and just knowing that the sooner we would say yes, the sooner a person would be able to leave detention,” Miles said.

At the border: The journey to asylum

Levine said most of Eduardo's time was spent in solitary confinement. She had no access to contact him.

“So, I just always had my phone on, ready to hear from him,” Levine said. “A lot of that time, he was deeply depressed. I was very worried about him.”

While in detention, Eduardo said inmates abused him psychologically and sexually. He said he witnessed violence, abuse and felt his life was at risk.

“When I turned myself into U.S immigration authorities, it was traumatizing,” Eduardo said. “I asked myself, ‘why is this happening to me? I’m not a criminal.’” They have people with criminal records of the worst. And you are mixed in with them. It was shocking, I kept asking myself, ‘why am I here?’"

Eduardo spent an additional two months at a different facility in Orange County. He said he couldn’t understand why he was being treated like a criminal when he was asking for help. He was placed in handcuffs, wore a “prisoner” uniform, and was confined to a small, solitary cell.

After two months in detention, Eduardo asked a judge to deport him to Mexico because he couldn’t stand it any longer.

"Every minute that went by, my life was at risk," Eduardo said. "I couldn’t stand it any longer. My life was at risk there. I didn’t know if I was in more danger in Mexico or at the prison.”

The judge warned him that if he chose self-deporting, he would not be able to step foot into the U.S., nor would be granted asylum either. When the judge heard the reasons why Eduardo was seeking asylum, something unique happened. The judge granted Eduardo was granted asylum at his first master calendar hearing, which is when asylum seekers are provided a date for their first hearing.

“It was the quickest asylum case in U.S. history,” Levine said.

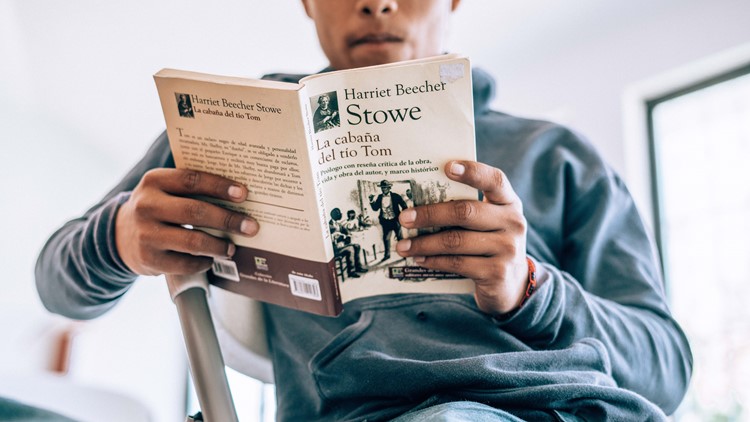

Eduardo is now working full-time at Javi's Cooking, a bakery in Oakland run by an Argentinian immigrant who came to the U.S. on a soccer scholarship.

“He's a really really good worker,” said Javi Sandes, owner of Javi’s Cooking. “He wants to learn. We talked in the beginning and I said look there is room to grow and you are in a really amazing country.”

Eduardo lives with Rachel and her roommates and is taking English lessons when he’s not working. The people who have helped him along the way were shocked at the judge’s response and say his case is the exception, not the rule.

Continue the conversation with Lilia on Facebook. If you're viewing on the ABC10 App, tap here for multimedia.

________________________________________________________________

WATCH PART ONE

WATCH PART TWO

________________________________________________________________

WATCH MORE:

Stories of men, women, and kids who risked death to get to the US-Mexico border, and how the situation looks from both sides.