SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Love was in the air early this year when the newly-inaugurated Gov. Gavin Newsom first proposed his first-ever state budget. Pacing the stage of a packed auditorium, he unveiled his ambitious, $209 billion plan with the studiousness of a policy wonk and the charm of an eager politician. He praised lawmakers by name, tossing verbal valentines at fellow Democrats whose majority party support he needed to approve the budget.

“I love this Legislature,” the governor declared.

As budget negotiations heated up over the spring, however, lawmakers weren’t as easily wooed as it may have seemed at the outset.

They pushed back against some of Newsom’s key proposals—to tie transportation funding for cities to their pace of housing development; add a new tax on water to cover the cost of toxic clean-up; tailor an existing health care council to focus only on developing a single-payer system; align California tax law with changes in federal tax law to pay for larger refunds for low-income residents. Outside the budget, lawmakers killed housing bills that would have helped build more homes and protect tenants from eviction or steep rent increases—complicating more Newsom campaign promises.

In the negotiations since, the Legislature and the governor have found enough common ground to advance most of Newsom’s budget priorities, using a different source of funding for the water clean-up, for example, conforming to some of the federal tax increases and adopting Newsom’s buzzwords for the health care council without changing its original mission. And the budget does include more than $2 billion to address the state’s housing crisis.

Still, Newsom’s learning curve has been apparent, not only compared to his predecessor, Jerry Brown, but compared to the Legislature, where term limits have raised the level of experience.

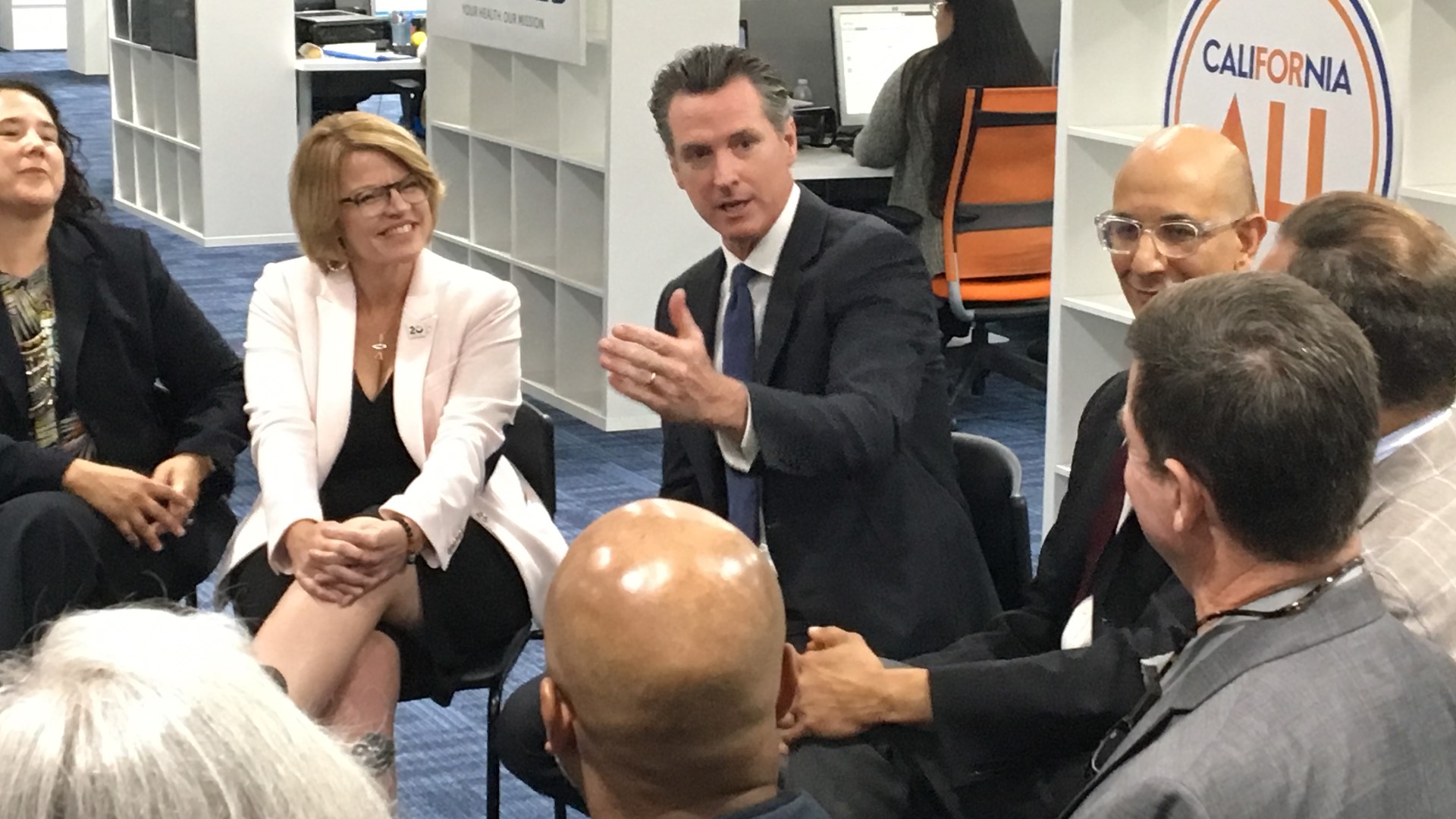

Six months into his job, Newsom is still figuring out how to work with a Legislature that feels more empowered to flex its muscles than many members did against Brown, who was not only a master of political strategery but also the longest-serving governor in California. Newsom’s enormous stack of priorities—reducing poverty, building more housing, expanding health care, changing criminal justice, improving services for children and families—has given lawmakers more opportunity to find common ground, but also more ways to push back.

“Unlike his predecessor who would pick one or two things to do each year,” said Mark Baldassare, president of the Public Policy Institute of California, “this is a governor who seems to pick one or two things to do every day.”

Newsom has downplayed the legislative pushback, saying he “couldn’t be more pleased” with the budget. “These are small issues to resolve,” he said. “They are important issues, but small differences.”

It’s true that the Legislature and governor are aligned on the vast majority of the $215 billion spending plan—helped, no doubt, by the fact that many of Newsom’s proposals were things lawmakers had floated in years past but been unable to convince Brown to fund: health care to undocumented young adults, an expansion of preschool, repealing taxes on diapers and menstrual products, funds to clean-up toxic drinking water.

And the Legislature occasionally bucked Brown too. They shunned his idea to link California’s electrical grid with other western states, for example, and refused to change liability laws for utility companies.

But the dynamic with Newsom differs in some significant ways. Many legislators were just toddlers when Brown was governor for the first time, contributing to the sense of gravitas he had in the Capitol. Newsom, at age 51, enters as their political contemporary.

Brown, in his last two terms, also worked with a rotating cast of legislative leaders as term limits forced many from office. Newsom is negotiating with more experienced Capitol players. Rendon is in his fourth year as Assembly speaker and has the potential to become the longest-serving speaker since Willie Brown. Senate leader Toni Atkins was the Assembly speaker from 2014 to 2016, making her the first Californian in more than a century to lead both houses of the Legislature.

Because voters approved a change in term limits several years ago, almost all of today’s lawmakers can be re-elected for up to 12 years. Many are now in their seventh year and anticipate remaining in office past the end of Newsom’s 4-year term.

“On policy, (Newsom) is largely aligned with us. I see very few areas where we are going to disagree,” Rendon predicted last year. “But ultimately, I do see the balance of power changing because we’ve been here for a while.”

Asked this month to assess that prediction, Rendon demurred, saying it’s too soon to judge. But he acknowledged that negotiating with Newsom has been different than it was with Brown. Newsom is more collaborative, he said, but Brown was more focused: “When somebody only cares about a couple issues, they can dig in on those issues.”

Another difference stems from how the current and former governors spend their time and money. Newsom is using both to befriend lawmakers. As he coasted to victory in last year’s general election, he donated more than $76,000 to 21 Democrats running for the Legislature, and often campaigned alongside them.

He also gave more than $200,000 to the state Democratic party, which spent heavily to help Democrats flip the House and win a historically huge majority in the Legislature. Brown spent his campaign money almost exclusively on ballot measures, and rarely made endorsements in legislative races.

Once they were elected, Brown invited lawmakers to perfunctory social events but didn’t devote much time to cultivating friendships with them. Newsom’s calendar from his first three months in office documents about two dozen meetings with individual legislators.

In an interview with CALmatters last year, Newsom acknowledged his “stylistic difference” from Brown. He noted, though, that after two terms as San Francisco’s top elected official, he’s not a complete novice in the art of political seduction.

“I’m not constitutionally capable of being, on certain issues, as strategic as Governor Brown is, in terms of when to engage,” Newsom said. “I tend to want to engage in everything early in the process. And that may be a liability.

“But it worked for me a little bit (as) mayor. Also caused some friction and setbacks, so I’ve learned some things.”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.