SACRAMENTO, Calif. — The Black Panther Party was a revolutionary organization, originally named The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

Young political activists Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale met as students at Merritt College in Oakland in 1961. Together, they founded the Black Panthers on Oct. 15, 1966, to protect Black people and their communities from police brutality and oppression.

The party recruited young Black people, including those experiencing poverty, into the organization to help make a positive change in historically marginalized and disenfranchised communities.

Like Civil Rights Leader Malcolm X, the Black Panthers believed nonviolent protests could not truly liberate Black people in the U.S. They confronted politicians, challenged police, and organized armed citizen patrols.

The Black Panther Party came into the national spotlight on May 2, 1967. On that date, Seale led a group of armed Black Panthers into the California State Capitol to protest against The Mulford Bill. On July 28, then-Governor Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law.

It prohibited "the carrying of a loaded firearm on one's person or in a vehicle while in any public place or on any public street in a prohibited area of unincorporated territory, except for specified law enforcement officers, military personnel, bank guards and messengers, sportsmen, private investigators and patrol operators, and persons authorized to carry concealable weapons."

Black Panthers quickly grew in popularity. By 1968, the Party had more the 2,000 members in major cities across the U.S.

Charles Brunson, who worked as a postman, founded the Sacramento Chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1968. Brunson opened the Black Panther office on 35th Street, near 5th Avenue and McClatchy Park, in the Oak Park neighborhood.

The Black Panthers created more than 35 survival and educational programs to support Black people, children, elderly, and low-income communities. They provided food, clothes, transportation, health clinics, sickle cell anemia screening, adult education, legal aid, and much more.

One of the most successful programs was the free breakfast offered to more than 20,000 school children each morning, nationwide.

In Sacramento, Black Panthers served breakfast to dozens of children at United Church of Christ on 4th Avenue. The party also gave away thousands of bags of groceries every month to families and the elderly.

Black Panthers started a Liberation School, also called Freedom School, at the Oak Park office to teach children Black history and other courses. The party provided a community newspaper called The Black Panther to help keep the public informed about the Party's doings, among other happenings in Black communities, nationwide.

The newspaper came with a list of guidelines, called "the 10-point program," to highlight the Black Panthers' beliefs. The 10 points are:

- We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

- We want full employment for our people.

- We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

- We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

- We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

- We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

- We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

- We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

- We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

- We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

More than 50 people eventually joined the Sacramento Chapter of The Black Panther Party, including young Black college students in the region and surrounding areas.

Despite growth, the Sacramento Chapter was soon forced to shut down. Law enforcement, including the Sacramento Police Department and Sacramento County Sheriff's Office, raided the Black Panther building in Oak Park on Father's Day 1969.

From the beginning, the FBI viewed the Black Panther Party as an enemy of the U.S. government. The agency worked to destroy the Party by using misinformation, intense surveillance, police harassment and lethal force. Those efforts were made through the agency's counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO).

The FBI's actions were so extreme the agency publicly apologized for "wrongful uses of power" in 1976. The press, along with other media organizations, also played a role in discrediting the Party through racist and imbalanced reporting, and creating mistrust and fear of Black Panthers and Black people.

Still, to this day, the legacy of the Black Panther Party lives on.

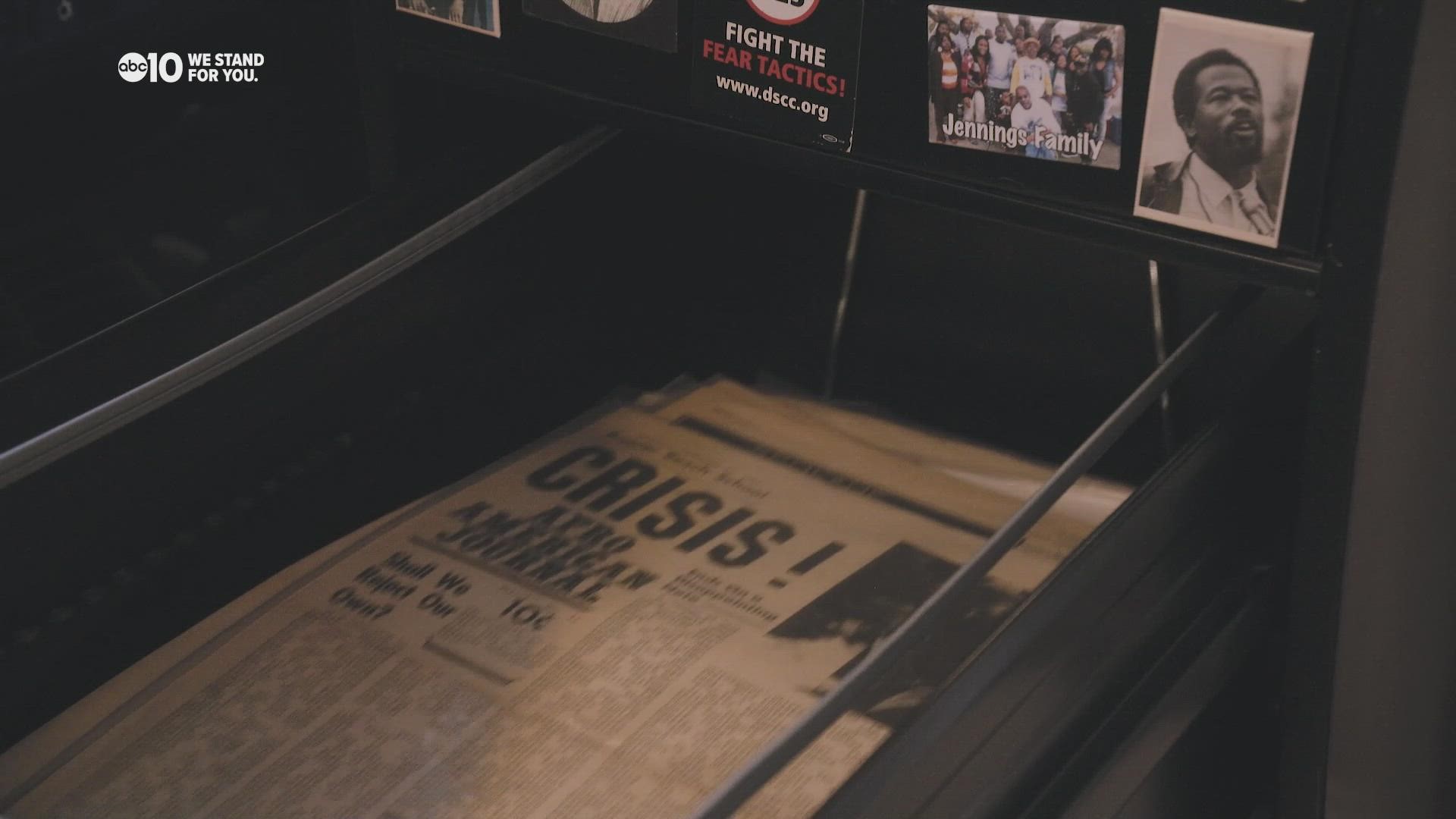

Bill Jennings lives in Sacramento's Curtis Park neighborhood. As a historian and former member of the Black Panther Party, he uses a personal archive room to tell the story of the Black Panthers. For more than 30 years, Jennings has collected thousands of historical artifacts, photographs, newspaper clippings and other memorabilia.

"Keeping the legacy of the Black Panther Party alive is very important," Jennings said. "I take it very serious. I have a whole basement of information, anything related to the Afro-American struggle during 1965 to 1975."

During the Black Power movement, Jennings was inspired to join the Black Panther Party. After becoming a member in Oakland, he says he began to work closely with founders Newton and Seale, along with other distinguished members of the group, to help Black people and communities organize, nationwide.

"During that time, 1965 and 1966, there was a lot of civil rights activity going on," Jennings said. "The Black Panther Party laid out a guideline of how to organize in the community. We would also follow police to make sure they wouldn't beat and brutalize people."

Now, Jennings works to help educate the public about the Black Panther Party. That includes helping to lead a Black Panther Party Legacy and Alumni group, called "It's About Time."

"There were maybe about 30 Panthers in Sacramento from the Bay Area," Jennings explained. "We started organizing a group called It's About Time. And, from 1996, we've been together. We put on reunions, too. I became in charge of doing exhibits. As the historian, I travel around the country to different museums, spreading the word about what the Black Panther Party was all about."

Jennings is not the only one working to keep the legacy of the Black Panthers alive. Jordan McGowan is the founder of Neighbor Program based in Sacramento. It's a "Pan-Afrikan socialist organization committed to serving the people and radically loving our neighbor."

Similar to the Black Panther Party, Neighbor Program offers a list of community services to the public. That includes free groceries, health and wellness clinics, legal aid, a community newspaper, and adult education classes.

Neighbor Program also operates a full-time transitional kindergarten through eighth grade community homeschool. It's called Malcolm X Academy for Afrikan Education. The academy is modeled after the Black Panthers' Liberation School, including Oakland Community School (OCS). It's the longest standing program of all the survival programs established by the Black Panthers.

Malcolm X Academy, along with all Neighbor Program community services, is housed at The Shakur Center in Sacramento's Oak Park neighborhood.

The Center opened last year, becoming the hub for Neighbor Program. A Black Panther Party flag flies outside of the building on 4th Avenue. For McGowan, he says it's a personal decision.

"When people see the Black Panther flag, it brings a great deal of pride," McGowan said. "My father, when he came home from Vietnam as a veteran, he was recruited into the Black Panther Party or to be associated with them in some capacity. I grew up, innately, aware of who I was, an Afrikan, of Malcolm X, of the Panthers."

McGowan, like Jennings, is encouraging others to learn more about The Black Panther Party, along with other significant Black leaders and groups, not just during Black History Month in February, but year-round.

"The Black Panthers represent dignity, pride, a history of who we are as Afrikans, and Afrikan resistance," McGowan said. "They demonstrated love, an undying love for their people, and that's who the Panthers are to us. So, keeping that legacy alive, it's also about survival, truthfully, how do we survive together."