'The plan was out the window': How the Camp Fire became California’s deadliest

An ABC10 Originals investigation finds the Paradise area was caught with no plan to evacuate people from a disaster the size of the Camp Fire. Many were caught in the wildfire's path with no knowledge of the evacuation orders issued for them.

If you're viewing on the ABC10 App, tap here for multimedia.

PARADISE, California — Eighty five people died when the Camp Fire burned down the town of Paradise and the surrounding neighborhoods of Concow and Magalia on Thursday, Nov. 8, 2018.

The fire forced the entire population to evacuate at once — an action emergency managers had actively avoided in their plans for handling wildfires.

There was no plan to handle an evacuation on this scale.

Some people became trapped, oblivious to the evacuation orders that had been issued for their homes.

Many had no warning as some notification systems went unused and others failed to reach large groups of people.

TWO CHOICES

"I HAD THE THINGS IN MY CAR... AND NOT MY MOM."

Christina Taft made a choice the day Paradise burned down.

She chose to run for her life. Now she regrets it.

“I was scared of dying because it just looked so bad outside,” Taft said. “I just wish I had done something different. I think about it every day wishing I could just you know reverse it all.”

Taft’s choice that day saved her life, but she couldn't convince her mom to leave the house with her.

“I had the things in my car and the car and not my mom,” Taft said. “That really hurts. It's like why didn't she get in? And why didn't I stay longer?”

After she escaped, Christina Taft tried over and over to get someone to go to the house to help her mother Vicki.

She figured she could call 911 for help, but there were only two dispatchers assigned to field calls that day. As the fire began to consume the town, thousands of calls poured in — activating an emergency spillover system so neighboring jurisdictions could answer.

When Christina got through, she learned the rescue she’d hoped to order for her mom didn't look likely.

“They told me they weren't getting anyone you couldn't get out themselves,” Christina Taft said. “That really shocked me and upset me. I was like, ‘my mom's gonna die now.’”

Is mom alive?

Christina could only wonder as the smoke plunged the town into an unearthly blackness.

The Camp Fire consumed the whole town between breakfast and dinnertime.

Sixty six-year-old Vicki Taft became another name on the list of hundreds missing.

Christina Taft’s mind kept going back to the choices: her own choice to leave, her mom’s choice to stay.

“We were fighting, so it was a really bad way to leave it,” Christina Taft said. “I didn't want to die and she wasn't going to listen to me.”

Words fail to describe the futility of this fight.

To say that time was “precious” at this moment doesn't do it justice. Time was life itself.

And yet, the two wasted a lot of it this way.

“For a whole hour, there was a lot being said,” Christina Taft recalls. “I think she was waiting for an authority.”

The authorities had decided already, but Christina and Vicki didn't know it.

The entire hour they spent fighting about whether to leave, their house was already under a mandatory evacuation order. But the order never reached them.

And they weren't the only ones.

A PERFECT FIRESTORM

THE CAMP FIRE BEGINS

IGNITION (6:29 A.M.)

14 MINUTES - FIRST CREW ARRIVES (6:43 A.M.)

“We have eyes on the vegetation fire, it's going to be very difficult to access,” said the voice on the radio.

That voice belonged to Matt McKenzie, a captain with CAL FIRE. He was the first to call back with a look at the flames.

The fire started just before sunrise in a canyon about eight miles from Paradise. They called it the “Camp Fire” because it started on Camp Creek Road, a scraggly dirt service road beneath the high tension power lines that ran down the steep canyon walls.

The road wasn't much use to fire crews. They couldn't get to the first flames in time to put them out.

McKenzie gauged the fire at 10 acres and growing fast. He knew this one could be big.

“We've got potential for a major incident,” McKenzie is heard saying over the radio. “It's got a really good wind on it. Critical rate of spread.”

To begin to grasp why it killed so many people, you need to understand that the Camp Fire wasn't just a bad fire.

It was a perfect firestorm.

26 MINUTES - FIRST MANDATORY EVACUATION (6:55 A.M.)

PULGA, A SMALL FOOTHILLS RESORT 7 MILES FROM PARADISE

31 MINUTES - SMOKE COLUMN APPROACHES PARADISE (7:00 A.M.)

A half-hour after ignition, Leland Ratcliff was in his truck driving from Paradise to Oroville. He was heading down the hill to his job as a firefighter with the Feather River Hotshots.

He saw the column of smoke in his rearview mirror, blowing sideways out of the canyon where it started.

“It was an ‘oh shit’ feeling because you see fire when it gets established in the canyon, it's notorious for large fires and gobbling firefighters up,” Ratcliff said.

He called a friend from his team who also lives in Paradise.

“He was right behind me, and he says, ‘oh shit,’" Ratcliff said. “It's going right for Paradise.”

52 MINUTES - MANDATORY EVACUATIONS FOR THE EAST SIDE OF PARADISE (7:21 A.M.)

1 HOUR, 1 MINUTE - THE FIRE REACHED THOUSANDS OF ACRES (7:30 A.M.)

Leland saw what was unfolding, what he calls a “doomsday column” of smoke heading toward town.

Roughly 40,000 people lived on the ridge. A lot of them were up there, including his kids and his wife.

He called her.

“I said, ‘Go get the kids from school and get home, get the cats, get the dogs, and get the hell out of there',” Ratcliff said. “She went to school, and at this point, the school was still accepting late arrivals because they hadn't gotten any kind of word to evacuate.”

“They just hadn't gotten any word that the fire was gonna be this bad.”

He wasn't being paranoid. Ratcliff’s training and experience told him exactly what that black column of smoke was doing as it blew sideways.

It was spreading the fire. It was full of hot embers.

THE HAILSTORM OF EMBERS

"YOU CAN'T START A FIRE ANY FASTER THAN THAT"

This perfect firestorm didn’t behave like the wildfires most people picture in their minds.

This fire had something far more pervasive than a wall of flames, something fire scientists call “ember cast,” created by the high wind and the terrain.

“You can't start a fire any faster than that, starting at the base of a dry hill that's burning up the hill on a really high wind that's blowing it up the hill,” said Hugh Safford, a research professor at UC Davis and the US Forest Service ecologist for all of California. “And at the top of that hill, the wind is catching the embers off the trees and throwing them out miles ahead of the fire.”

Those embers rained down on every part of Paradise.

Fire crews couldn’t steer the Camp Fire, much less head it off.

It was a windstorm full of sparks, which flew right over their heads and lit a million spot fires.

Rescuers started to get calls from people who can’t escape.

THE WARNED AND THE UNWARNED

THE FIRST EVACUATIONS

1 HOUR, 24 MINUTES - REPORTS OF PEOPLE TRAPPED IN THE FIRE (7:53 A.M.)

1 HOUR, 34 MINUTES - THE FIRST RADIO CALL TO EVACUATE PARADISE (8:03 A.M.)

“The town of Paradise is under mandatory evacuation,” said a dispatcher’s voice on the fire radio channel.

She repeated it so all the crews could hear. Still, there was confusion from the start.

Despite the all-town evacuation heard on the firefighter radio, the first alerts to people who live in Paradise town limits started to go out around this time — not for the whole town, but select parts of it.

“It's really starting to be impending doom,” Ratcliff said.

The hotshot crew Ratcliff worked with didn’t wait to be called.

They loaded up in their transport truck and headed toward the fire, deciding the best they could do was to go door-to-door to warn people.

They swung by Leland’s house near Clark Road and Pearson.

“My wife is still here. And I said, ‘Well, what the hell are you still doing here?’ At that point, she was hopping in the car and they took off,” Ratcliff said. “They got out of here before any of the mass chaos, panic could happen. They got down the hill, luckily, in plenty of time.”

2 HOURS, 1 MINUTE - LELAND RATCLIFF’S WIFE EVACUATES (8:30 A.M.)

2 HOURS, 1 MINUTE - A NEIGHBOR WAKES CHRISTINA AND Vicki TAFT (8:30 A.M.)

Vicki and Christina Taft were awoken by a knock on the door. Christina says a neighbor had heard about a fire in the hills, but didn’t know much about what the fire was doing.

There was a faint smell of smoke in the air.

“I just kind of took a shower and got ready and then started seriously packing seeing the cars outside starting to back up,” Christina Taft remembers. “My mom was making phone calls, lightly packing, kind of thinking it would just be fine.”

Christina says her mom paid the phone bill and spent the morning calling friends in town, none of them were evacuating. That’s when Christina and Vicki Taft started fighting about whether to leave.

They couldn’t see flames at this point, but the smoke was getting thicker. They weren't told they needed to evacuate.

A lot of people hadn’t.

“They expected that an authority would tell them, like every other fire like that we had we were told,” Christina Taft said.

If you weren’t actually there, you might argue this is where common sense should kick in. In fact, that’s the argument Christina Taft was making to her mom.

But it’s not that simple.

By staying put, Vicki Taft was doing what local emergency planners spent the last decade trying to convince everyone to do: wait for their zone to be called.

NO PLAN FOR THIS

"WE LEARNED NOT TO EVACUATE EVERYBODY AT ONCE"

Paradise had a good plan for most fires, but not this one.

What Paradise needed in the Camp Fire was to evacuate everybody at once, but the community actively planned against doing that.

Perhaps no one put it more plainly than former Paradise town councilman Woody Culleton, “We learned not to evacuate everybody at once.”

Culleton uttered those words during a 2015 meeting to update evacuation plans. It wasn't just his opinion. This was accepted wisdom, a lesson learned from the Humboldt Fire in 2008, when the roads jammed up on the ridge around Paradise during mass evacuations.

As a result, the community improved some of its roads and made a plan to reverse the directions of lanes to get more people out in a bad fire.

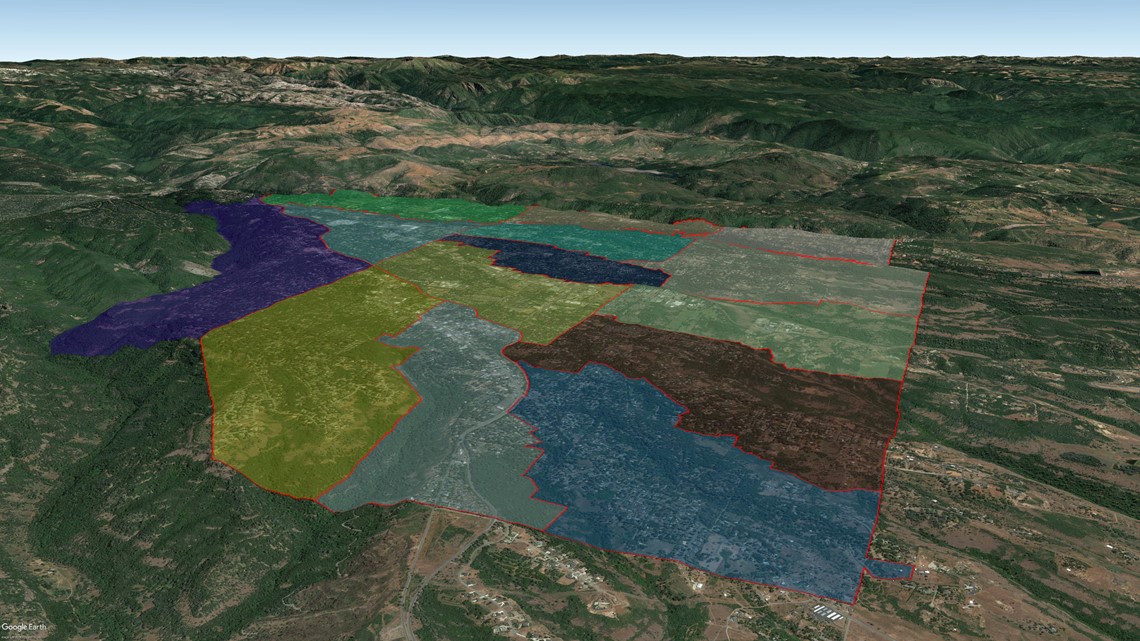

It also split all the neighborhoods into zones.

Paradise had 14 evacuation zones, along with many more for the neighborhoods outside town limits.

The idea was to evacuate only those who needed to escape — a strategy to keep roads flowing.

“There was never a whole-town evacuation plan,” said current Paradise town councilman Mike Zuccolillo.

Zuccolillo says he jumped in to help direct traffic on the day of the fire. The evacuation plans didn't cover this situation. He wasn't sure what to do.

“Do we try to hold up the traffic to get the firetruck up or do we let the firetrucks hold and just keep running the traffic down the hill,” Zuccolillo remembers wondering. “You were making decisions right on the spot because the plan was out the window. At that point, the plan was get as many people off as we get off this hill as quickly as possible.”

The plan may have been out the window, but the “go when your zone is called” mentality was already baked into the culture here.

On the emergency traffic plan document for Paradise, goal number one was to “prevent people from entering the evacuation area and becoming an additional burden upon the road system.”

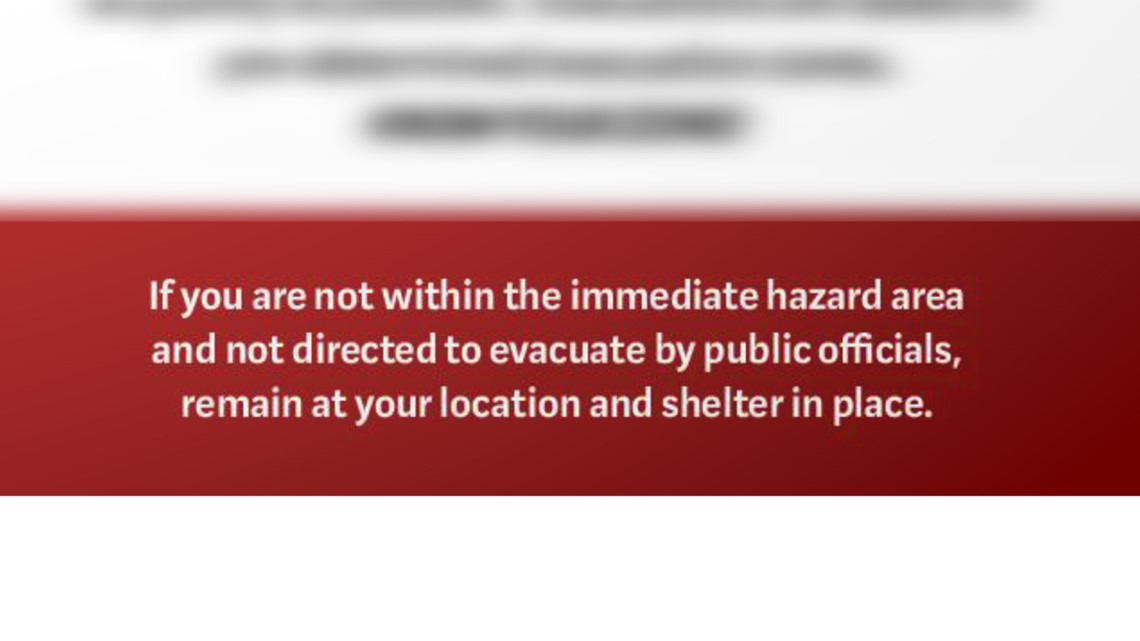

The front page of the area’s evacuation pamphlet warned people to “KNOW YOUR ZONE” and “if you are not within the immediate hazard area and not directed to evacuate by public officials, remain at your location and shelter in place.”

They did.

“A lot of people probably figured they could shelter in place. Because there was never a concept of everything burning," Zuccolillo said. “Unfortunately, a lot of people that passed, passed in their homes. If they had received notice that you were going to burn to death, people maybe would have tried differently.”

SHELTER IN PLACE

"SHE WAS HIDING IN HER HOUSE"

3 HOURS, 31 MINUTES - CHRISTINA TAFT LEAVES. Vicki TAFT STAYS. (10:00 A.M.)

“The lights went out and then I was like, ‘well we definitely should leave now',” Christina Taft said. “It kept getting darker outside and just like we were fighting, and I even said ‘I'm leaving.’ And she said ‘leave.’”

Her mom wouldn't budge and Christina felt her life was in danger.

It was.

“I tried and it didn't work. I mean I did try. I just didn't make the right decision,” Taft says. “She didn't either.”

A week after the fire, Christina got word that crews found human remains in the house. She gave a DNA sample.

Another week later, on Thanksgiving morning, she got the phone call: The body was her mom’s. Vicki Taft died in her living room as fire consumed the house.

“She didn’t want to die and I knew it was bad. She don't realize it's gonna be bad. She was hiding in her house,” Christina Taft said. “If I had stayed, she'd probably be alive now.”

CONFUSION AND DELAYS IN SHARING ORDERS

ORDERS OVERLAPPED AND NOTIFICATIONS LAGGED

The rescuers working that day didn't want Vicki to die in her house.

In fact, before Christina left at 10 a.m., authorities issued at least three evacuation orders that included the Taft house.

The first was almost two hours before Christina left. It was called out and repeated to fire crews over the radio at 8:03 a.m.: “The town of Paradise is under mandatory evacuation.”

The first attempt to communicate evacuation orders to zones of Paradise wouldn't come for nearly half an hour.

Despite that radio order for the whole town, the Butte County Sheriff’s office issued another mandatory evacuation order for only four specific zones of Paradise, including Zone 6 where the Tafts lived. That was at 8:32 a.m.

Another whole-town evacuation order can be heard on the fire radio at 9:04 a.m. The sheriff’s office used social media, too. The sheriff’s office issued a tweet to evacuate the Taft’s zone almost an hour and a half before Christina and Vicki Taft parted ways.

Looking at that tweet is painful for Christina. It’s the order she thinks her mom was waiting for.

“It really hurts that they put this out here and they wouldn't tell us,” Christina Taft said.

An order unheard is as good as no order at all. None of the evacuation orders reached the Tafts.

They weren't alone.

THE ORDER UNHEARD

MOST OF THE DEAD WERE FOUND IN HOMES OR OUTSIDE

If you talk to enough survivors of the Camp Fire, you’ll hear this over and over: many got no warning at all.

Some of the 85 people who died were found in their cars trying to evacuate. But most died outside running for their lives or inside their homes, like Vicki Taft did. Two-thirds of the dead were found inside their homes.

Leland Ratcliff saw masses of people who didn’t know to evacuate until the embers started falling on them.

“We picked up grandmas on the side of the road that were just barely able to make it up the side of the road,” Ratcliff said. “Fifteen-year-old kids that didn't know where to go. [We] just started throwing people in the truck.”

Those masses didn’t know what to do for a couple of reasons.

First, there simply weren’t enough rescuers in Paradise that morning to go to visit every street and warn people. Many of those who were in the area were dispatched to high-priority facilities such as Feather River Hospital, nursing and retirement homes, and local schools and daycare centers.

Second, our investigation found that county and town officials did not use all of the mass notification systems they had available — and the one system it did use failed to reach a lot of people.

CODE RED ALERTS

OPT-IN NOTICES FAILED TO REACH THOUSANDS

The county used a service called Code Red, which is a robocall alert system.

This service comes with a built-in limitation: users need to sign-up in advance to get alerts. It’s an “opt-in” service.

Mike Zuccolillo says only about 1 in 8 people tell him they got a mass notification that day. He was signed up for Code Red and says he didn't get an electronic alert of any kind.

“Nothing,” he said.

A review of the call logs from that day shows the Code Red alerts couldn't keep up with the fire. The service is only as capable as the phone lines, which can only handle so many calls at once.

At a time when seconds mattered, it took the system 16 minutes to call the phone numbers for the first evacuation zones in Paradise: Zones 2, 6, 7, and 13 were all included at that order.

The system attempted to make 11,169 calls to 4,459 numbers to share that order. It failed to reach almost a third of those phone numbers, a rate that would get worse as utility lines burned up.

In this first round of Code Red alerts for Paradise zones, 1,664 phone lines that signed up were never reached.

WIRELESS AND BROADCAST ALERTS NOT USED

FEMA CONFIRMS NO ACTIVATIONS FROM CALIFORNIA ON NOV. 8

There are two federally-managed alert systems that could have been used to reach masses of people, even if they’d never signed up.

But responders never used them.

The Emergency Alert System (EAS) could have sent out warnings on TV and radio stations all over Butte County. The Wireless Emergency Alert system (WEA) could have pushed a warning to cell phones in the area.

Both systems are managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which confirmed to us that no alerts were ordered from any agency in California the day of the fire.

Rescuers gave the order to abandon ship, but they never used the biggest bullhorn they had to spread the word.

Sheriff Kory Honea, whose office issued the majority of evacuation orders that day, said he’s not certain that there was a conscious decision against using EAS and WEA alerts, but it wasn’t the kind of thing the zone-by-zone plans called for.

“I think it's certainly worth taking a look at,” Honea said. “We were working the plan that we had.”

Honea himself wasn’t issuing evacuation orders that morning, he’d joined rescue crews on the ground to help people. He says the radio channels were overloaded and phone service was sporadic on the ridge as cars headed down all lanes of Skyway, the main drag through town.

He believes the existing plan can be credited for saving the lives of many people who got out. Honea points out that second-guessing what alerts would have been effective can be a tricky exercise, given the fact that the fire knocked out cell phone towers and telecommunication lines.

Honea acknowledges that some people may have died without receiving an evacuation order, but he’s just not sure how many additional lives could have been saved.

“I would submit to you that there's probably not a single jurisdiction in California, or for that matter probably in this country, that has the capacity to evacuate the entire population at one time so quickly,” Honea said.

AN IMMEDIATE LESSON

HUNDREDS OF TOWNS FACE SIMILAR RISK

The survivors of the Camp Fire will have to live with an uncomfortable question: if there were a plan for the worst possible firestorm, how many of our friends, family and neighbors could have been saved?

“No one ever came to us and said, ‘You know what. You could have a town-wide evacuation and you could lose everything in town,’” Zuccolillo said. “No one ever told us that.”

That’s unfortunate.

Fire scientists are surprised at the high death toll of this fire, but they’ve worried for some time that a fire just like this one could burn down an entire town at once.

The danger gets worse each year as fuel accumulates, temperatures warm, and throngs of people continue to flock to affordable neighborhoods built in California’s foothills and mountains.

There are a lot of Paradises in California.

“There are hundreds of towns in the Sierra that are realistically in areas just as risky fire-wise as the situation was in Paradise,” said forest service ecologist Hugh Safford. “There are some dice being rolled.”

There’s a lesson the leaders of Paradise want all those other Paradises to know:

“It could happen,” Zuccolillo said. “I mean, today this is the worst tragedy that's ever happened. I hope I'm the last person that says that. I hope there's not another town.”

Any community that hasn’t got an “abandon ship” plan should hold a special meeting now to start thinking about what they’d do in a fire that exceeds their predictions.

Paradise had its own vulnerabilities: one in five people under 65 had a disability and one in four were over age 65, according to US Census data. Both rates are much higher than the state average and it’s reflected in the fact that most of the 85 dead were elderly.

In hindsight, leaders are looking at warning options they didn’t have before.

“Air raid horns. Similar to tornado horns. Maybe that's more of a concept up here because you know we did have a more elderly population,” Zuccolillo said.

“I think that's something that going forward would be a good idea,” said Sheriff Honea. “The one problem you have to consider... you need to know what [the alarm] means. Because at three o'clock the morning when the air raid siren goes off, well what does that mean? Right? What do we do?”

Sirens are merely one example of the solutions Paradise and communities like it might consider as they look at how to plan for the next perfect storm. We can’t prevent every fire. Sparks happen. But no one thinks a spark should kill this many people.

‘SO MOM DIDN’T DIE IN VAIN’

TURNING LOSS INTO ACTION

“It was up to me to help her and I didn't. I left early,” Christina Taft said.”I have to live with that decision forever.”

Christina Taft carries a heavy burden now. She’s heard anecdotal stories of people waiting longer than she did, but escaping.

She called herself a “coward” for not waiting longer.

That’s not really fair when you consider the fact that some people burned in their cars trying to escape down the wrong road at the wrong time in the Camp Fire, but the heart can’t always be comforted by things the brain knows.

There is some comfort, though, in an honest conversation about why the fire took the lives it did.

“If there's some kind of change I feel like that would help, too,” Christina Taft said. “So it didn't keep happening. Something good. So my mom didn't die in vain.”

If enough people get that message, maybe the Camp Fire will remain the deadliest fire in California history forever.

At least, that’s the hope.

ABC10 journalists Michael Anthony Adams, John Bartell, Jason Beal, Mike Bunnell, Pedro Garcia, Mike Gaza, Gonzalo Magaña, and Chelsea Shannon contributed to this report.