If you're viewing on the ABC10 App, tap here for multimedia.

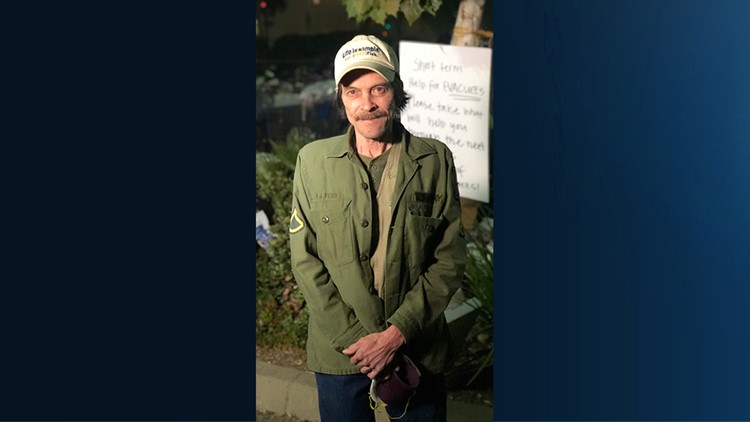

CHICO, Calif. (AP) — Bob Talk hadn't even transferred the title for his new trailer — the one that was supposed to get him off the streets — when Northern California's deadly wildfire whipped through and turned it to ash. He had lived in the trailer park in Paradise for all of three days.

Talk is now among hundreds of people still in a shelter a month later.

The future is uncertain for all of the fire's victims, but it's uniquely challenging for the many like Talk who were already living on the edge, homeless or nearly so, before escaping with their lives and little else.

"I don't know what I'm going to do," Talk said as he ate fruit and salad in the dining hall of a Red Cross shelter, his dog on his lap. "But I'm not going to leave this town."

Talk, 61, said he had set aside $500 a month from a public assistance check to buy the trailer for $3,500. The plan was to move in with his 39-year-old daughter and host a Christmas party. The extended family would be excited to be off the street. But his daughter was struck and killed by a car while riding her bike Oct. 3.

When the flames swept through Butte County on Nov. 8, killing at least 85 people in the nation's deadliest wildfire in a century, Talk hitched a ride to safety with a sheriff's deputy. He ended up staying in a Walmart parking lot in nearby Chico that became an unofficial shelter, where people with nowhere else to go pitched tents or slept in their cars.

Last week, the final holdouts, including Talk, were sent to the Red Cross shelter at the Silver Dollar Fairgrounds in Chico.

Talk wasn't sure how long he would stay — "Maybe I'll meet my future ex-wife in here," he joked — or what he would do next. But he knows he will be in Chico, where he was born and raised before he started working at carnivals for 40 years.

"I like adventure," he said. "Every time I walk out that door I make an adventure."

The shelter gets him out of the cold and lets him come and go as he pleases. His only complaint: There's a designated area to smoke cigarettes but nowhere to light up marijuana, which is legal in California.

Eighteen percent of the people in Butte County, population 230,000, live in poverty. The median household income is about $47,000 — $20,000 less than the statewide figure.

The Red Cross is consolidating shelters that cropped up across Northern California into one center at the fairgrounds, where about 450 people were staying as of Wednesday night. Red Cross spokesman Stephen Walsh said the agency is working with the local government and nonprofit organizations to find longer-term housing for people, whether they were homeless before the disaster or not.

A snapshot survey found nearly 2,000 homeless people in Butte County on one January night in 2017, the most recent count. That was before the blaze destroyed 14,000 homes.

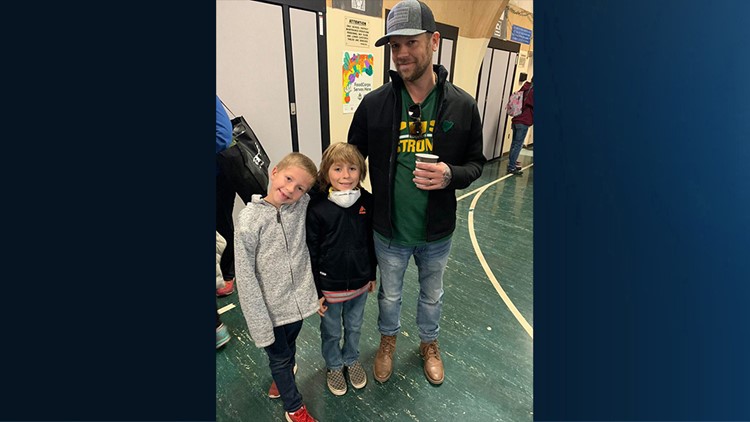

Michael Jones, 36, was one of the last to leave the Walmart parking lot. His disabled pickup truck was towed to the fairgrounds, where he is now staying and where he had his first shower in two weeks.

Jones had moved to Paradise about seven months ago to help take care of his mother after quitting his job as a millwright in Sacramento.

The tow-behind trailer where he had been living was destroyed in the fire. A lawyer gave him automobile parts, and he is hoping a mechanic will fix the truck for little or nothing. He is looking for work and wants to stay close to Paradise.

Jones said the fire has forced him to get back to the basics in life, and he is excited for the future despite it all.

"Minimalistic living is becoming more popular. This way, I get a head start into that," Jones said. "I feel oddly liberated by this thing."

Camp Fire: Faces of the Fire

The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimates there are 2,500 families eligible for a voucher to stay in a hotel, but only about 200 have obtained one, said Kevin Hannes, an agency official. He said he expects interest to rise after people get a chance to see their damaged or destroyed homes.

Steve Wilson, who was homeless in Chico before the disaster, has seen the streets grow more crowded with people like him. Hustling for handouts has gotten tougher because people are giving their money to fire victims instead, he said.

On Tuesday, he said, security guards tried to clear him from the parking lot at an abandoned Toys R Us where he had been staying. They backed off after he complained that they weren't hassling others there who were homeless because of the fire, he said.

There's also been a certain benefit to the outpouring of support for those affected by the fire.

"Before the fire, the homeless around here, you couldn't pitch a tent," Wilson said. "The law enforcement, they didn't want us pitching tents. Then with the fire, they can't find us because we're blending in with them."

Watch now... A cafe owner steps in to help when a Redding man faces an unspeakable tragedy in the aftermath of the Carr Fire: