POLLOCK PINES, Calif. — Record-setting blazes raging across Northern California are wiping out forests central to plans to reduce carbon emissions and testing projects designed to protect communities, the state’s top fire official said Wednesday, hours before a fast-moving new blaze erupted.

Fires that are “exceedingly resistant to control” in drought-sapped vegetation are on pace to exceed the amount of land burned last year — the most in modern history — and having broader effects, said Thom Porter, chief of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Hours after Porter spoke, a grass fire spurred by winds up to 30 mph (48 kilometers per hour) swiftly burned dozens of homes, forced the evacuation of schools and threatened the city of Clearlake about 80 miles north of San Francisco.

Rows of homes were destroyed on at least two blocks and television footage showed crews dousing burning homes with water. Children were rushed out of an elementary school as a field across the street burned.

Lake County Sheriff Brian Martin issued a warning of “immediate threat to life and property."

“This isn’t the fire to mess around with,” he told KGO-TV.

Fires burning mostly in the northern part of the state threatened thousands of homes and led to extended evacuation orders and warnings, as well as power outages to prevent utility equipment from sparking fires amid strong winds.

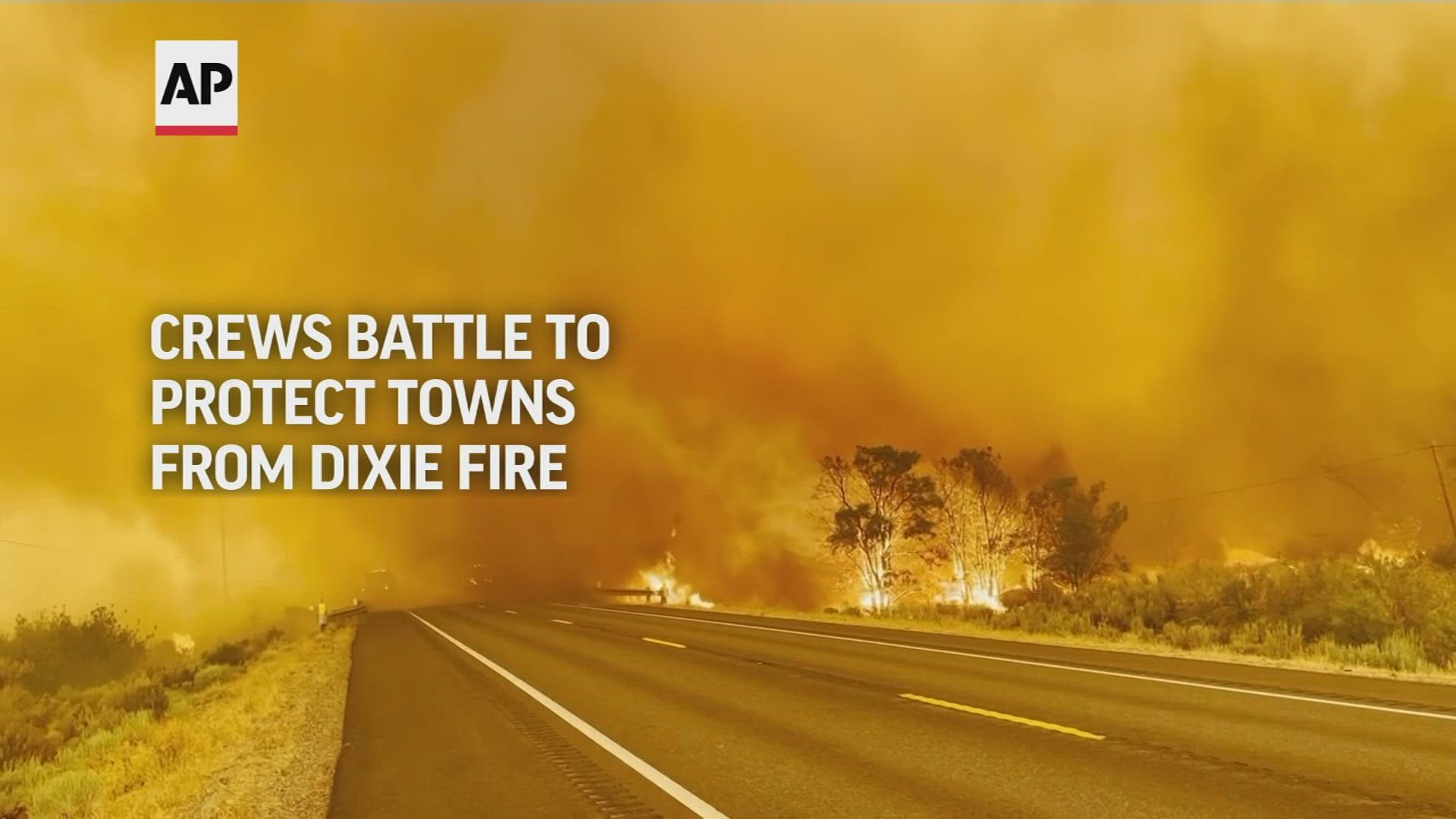

The largest current fire in the West, known as the Dixie Fire, is the first to have burned from east to west across the spine of California, where the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains meet, the state's fire chief said.

It was also one of several massive fires that have destroyed areas of the timber belt that serve as a centerpiece of the state's climate reduction plan because trees can store carbon dioxide.

“We are seeing generational destruction of forests because of what these fires are doing,” Porter said. “This is going to take a long time to come back from.”

Although the Dixie Fire is only a third contained and remains a threat, dozens of fire engines and crews were transferred Wednesday to fight the Caldor Fire, which exploded in size southwest of Lake Tahoe and ravaged Grizzly Flats, a community of about 1,200. It covered 84 square miles (217 square kilometers).

Dozens of homes burned, according to officials, but tallies were incomplete. Those who viewed the aftermath saw few homes standing. Lone chimneys rose from the ashes, little more than rows of chairs remained of a church and the burned out husks of cars littered the landscape.

Chris Sheean said the dream home he bought six weeks ago near the elementary school went up in smoke. He felt lucky he and his wife, cats and dog got out safely hours before the flames arrived.

“It’s devastation. You know, there’s really no way to explain the feeling, the loss,” Sheean said. “Maybe next to losing a child, a baby, maybe. … Everything that we owned, everything that we’ve built is gone.”

All 7,000 residents in nearby Pollock Pines were ordered to evacuate Tuesday. A large fire menaced the town in 2014.

Time lapse video from a U.S. Forest Service webcam captured the fire's extreme behavior as it grew beneath a massive gray cloud. A ceiling of dark smoke spread out from the main plume that began to glow and was then illuminated by flames shooting hundreds of feet in the sky.

John Battles, a professor of forest ecology at the University of California, Berkeley, said the fires are behaving in ways not seen in the past as flames churn through trees and brush desiccated by a megadrought in the West and exacerbated by climate change.

“These are reburning areas that have burned what we thought were big fires 10 years ago,” Battles said. “They’re reburning that landscape.”

The wildfires, in large part, have been fueled by high temperatures, strong winds and dry weather. Climate change has made the U.S. West warmer and drier in the past 30 years and will continue to make the weather more extreme and wildfires more destructive, according to scientists.

Battles said the fires have created a vicious cycle. Burning increases carbon emissions while also destroying trees and other ground cover that can absorb the greenhouse gas. Dead trees will continue to release carbon they once stored.

The fire is burning along the U.S. Route 50 corridor, one of two highways between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. The highway through the canyon along the South Fork of the American River has been the focus of a decades-long effort to protect homes by preventing the spread of fires through a combination of fuel breaks, prescribed burns and logging.

“All of that is being tested as we speak,” Porter said. “When fire is jumping outside of its perimeter, sometimes miles ... those fuel projects won’t stop a fire. Sometimes they’re just used to slow it enough to get people out of the way.”

In the Sierra-Cascades region about 100 miles (161 kilometers) to the north, the month-old Dixie Fire expanded by thousands of acres to 993 square miles (2,572 square kilometers) — two weeks after the blaze gutted the Gold Rush-era town of Greenville. About 16,000 homes and buildings were threatened by the Dixie Fire, the second-largest in state history.

“It's a pretty good size monster," Mark Brunton, a firefighting operations section chief, said in a briefing. "It's going to be a work in progress — eating the elephant one bite at a time kind of thing.”

The Caldor and Dixie fires are among a dozen large wildfires in the northern half of California.

More than 40,000 Pacific Gas & Electric customers had no power, though the utility began restoring electricity to customers as forecasts for low humidity and gusts were expected to improve Thursday.

Most of the fires this year have hit the northern part of the state, largely sparing Southern California, which experienced rare drizzle and light rain Wednesday. Fire conditions in the region are expected to get worse in the fall.

___

Associated Press writers John Antczak in Los Angeles and Olga R. Rodriguez and Janie Har in San Francisco contributed to this report.