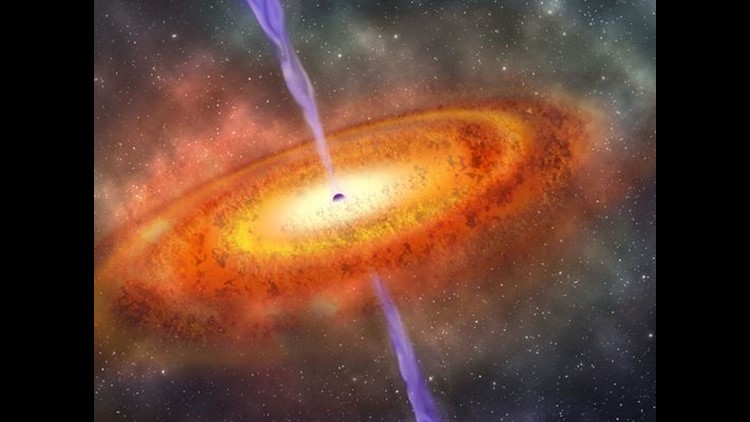

The most distant and oldest supermassive black hole ever seen has been discovered, astronomers announced in a study published Wednesday.

The black hole resides in a quasar and its light reaches us from when the universe was only 5% of its current age — over 13 billion years ago, or "just" 690 million years after the Big Bang.

Quasars are among the brightest and most-distant known celestial objects and are crucial to understanding the early universe, said study co-author Bram Venemans of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

The discovery of a massive black hole so early in the universe may provide key clues on conditions at that time, which allowed for huge black holes to form.

It's a truly gargantuan black hole, some 800 million times the mass of our sun. The size amazed and puzzled astronomers.

“This black hole grew far larger than we expected in only 690 million years after the Big Bang, which challenges our theories about how black holes form,” said study co-author Daniel Stern of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Study lead author Eduardo Bañados of the Carnegie Institution for Science said that "gathering all this mass in fewer than 690 million years is an enormous challenge for theories of supermassive black hole growth.”

This is very unlike the black holes that form in the present-day universe, which rarely exceed a few dozen solar masses.

Another study author, Robert Simcoe of MIT, said “this is the only object we have observed from this era. It has an extremely high mass, and yet the universe is so young that this thing shouldn’t exist. The universe was just not old enough to make a black hole that big. It’s very puzzling.”

The unexpected discovery was based on data gathered from observatories around the world. It's part of a long-term search for the earliest quasars, which will continue. Even older examples could be discovered, scientists said.

The discovery was found by scouring the new generation of wide-area, sensitive surveys astronomers are conducting using NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer in orbit and ground-based telescopes in Chile and Hawaii, Stern said.

"This is a very exciting discovery," he said. “With several next-generation, even-more-sensitive facilities currently being built, we can expect many exciting discoveries in the very early universe in the coming years.”

The study was published in the British journal Nature.