SACRAMENTO, Calif. — The smoke has (partly) cleared from the legislative battlefield, in the aftermath of a struggle pitting the leader of the California Senate against not only powerful water and agricultural interests but also Gov. Gavin Newsom. And California’s two largest water-delivery systems may soon be operating under rules that differ ever more significantly.

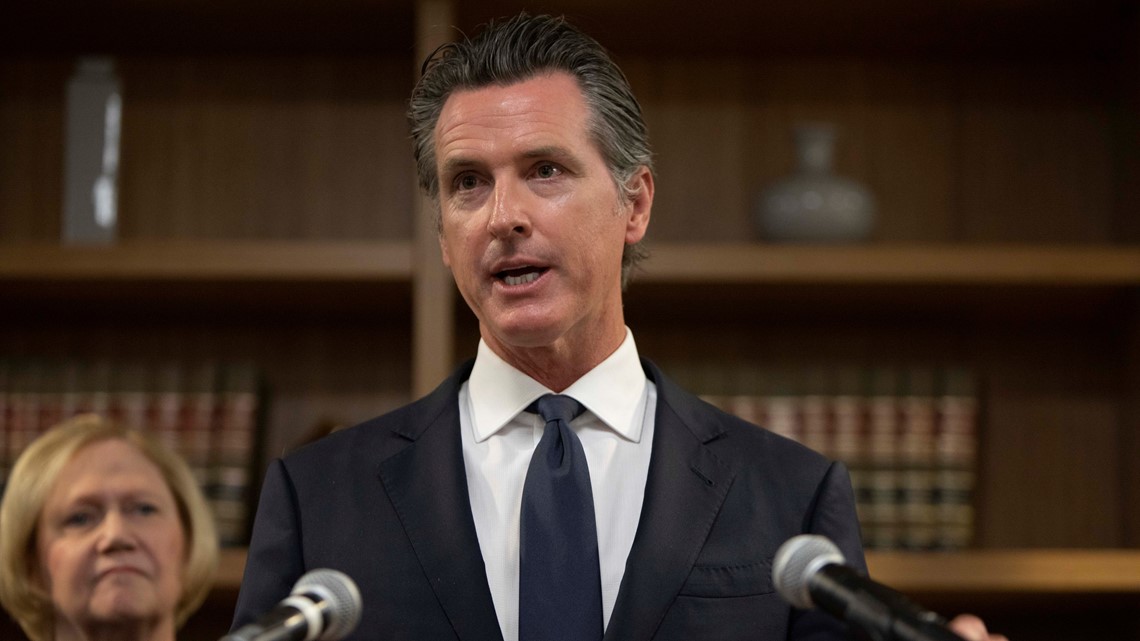

Newsom has said he won’t approve Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins’ bid for a legal backstop against environmental rollbacks by the Trump administration. And Washington is poised to reduce protections for endangered fish species in the state’s largest watersheds.

The result may be the heightened regulatory uncertainty that opponents of the bill said they hoped to avoid: While the federal water managers could begin sending more supplies to contractors and agricultural users, state authorities — who adhere to stricter standards for species and habitat protection in the waters they control — could compensate by providing less for cities.

Both state and federal managers have worked for years to harmonize their disparate rules as much as practicable. But now the potential for incompatible management of California’s critical water resources may also create more legal wrangling, experts say, rather than establish a level playing field and resolve the state’s longstanding water wars.

“There’s going to continue to be litigation,” said Holly Doremus, a professor of environmental regulation at UC Berkeley’s law school. “I would think it would help the state to have as much control as it can over water operations.

“California water law imposes requirements that federal law does not; California water law is more protective of the environment,” she said. “The state and the federal government have very different views.”

Atkins, a San Diego Democrat, authored the bill, SB 1, which the Legislature passed. It would require the state to assess proposed changes to U.S. environmental and workplace-safety laws. If the new federal rules were to be less stringent than those in place on January 19, 2017 — the day before Trump took office — California officials could either adopt the pre-Trump standards or impose stricter ones.

The thorniest part of the bill involves endangered-species protections and the resulting implications for water supplies. Protection of endangered fish and their habitat restricts water flow in certain places at key times of the year, and farmers and water brokers oppose those constraints, which limit their supplies.

Trump plans to significantly change how U.S. species law is implemented, which could mean more water for farmers at the expense of the Delta smelt, salmon and other fish.

Newsom says Atkins’ bill would disrupt a collaborative, and voluntary, approach to water management. He called the measure “a solution in search of a problem” and is expected to veto it.

Atkins avoided a direct public challenge to Newsom but said in a written statement, “SB 1 is the product of a full year’s worth of work, so clearly I am strongly disappointed in its impending fate.”

In staking out his position, Newsom is caught between his fellow Democrats and environmentalists on one side, and his relationship with Central Valley farmers and water brokers and sympathy for their needs on the other.

The Central Valley water project, run by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, provides water for those farmers as well as flood control and water for Sacramento and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Newsom has sunk political capital into the region — and literal capital, too. His administration recently committed $70 million to support the voluntary agreement, funding habitat restoration and projects to enhance water quality.

The agreement is important to Newsom, who has coaxed the various water interests into signing a pact to manage flows from the Sacramento and San Joaquin River systems in the Delta Estuary. That process is nearing a conclusion.

And, although Newsom and other opponents claimed the bill would have derailed the agreement, Atkins’ legislation specifically notes that it would have no effect on it: “This article does not affect the process by which voluntary agreements are entered into to assist in the implementation of new water quality standards lawfully adopted.”

Water agencies and others see the anticipated federal changes, coupled with the voluntary accord, as an opportunity to redefine how water is managed in the state, one of the most complex and fraught issues in California.

“I firmly believe it would be one of the most signal accomplishments in my lifetime if we could achieve comprehensive management across the Delta,” said Dave Eggerton, Executive Director of the Association of California Water Agencies. “That would be amazing.”

Both the state and federal water projects are in the midst of recalibrating plans. The state has been regulating the amount of water flowing in and out of the Delta, which has angered Central Valley farmers, who irrigate some 3 million agricultural acres.

The state’s plan update is coming out in phases, and the voluntary agreement could be incorporated into the next update. A revised version of the agreement is expected by the end of October, according to Lisa Lien-Mager, a spokeswoman for the state Natural Resources Agency.

Trump has promised farmers they would receive more federal water. Last year he signed a memorandum directing federal agencies to “minimize unnecessary regulatory burdens,” streamline environmental reviews and accelerate water deliveries to the Central Valley.

An updated biological review is also expected soon, and “the smart money is that the new biological opinion will be more permissive (than) the old one,” said Doremus.

That may give the state a legal window, she said, to assert that the Trump administration’s water pumping won’t adequately protect a precious state resource — water. That legal argument, called the “public trust doctrine,” would almost certainly require a court to sort out.

While much of the debate over the bill focused on water, the measure also applied broadly to air regulations and employee safety in the workplace. Earlier this year, the Trump administration announced a new rule eliminating the requirement to report workplace injuries or illness in detailed electronic reports to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Six states sued to reverse the rule, though California was not among them.

California does not need Atkins’ legislation to respond to federal rollbacks with new rules of its own. But in the case of imperiled species, implementing new rules could take years.

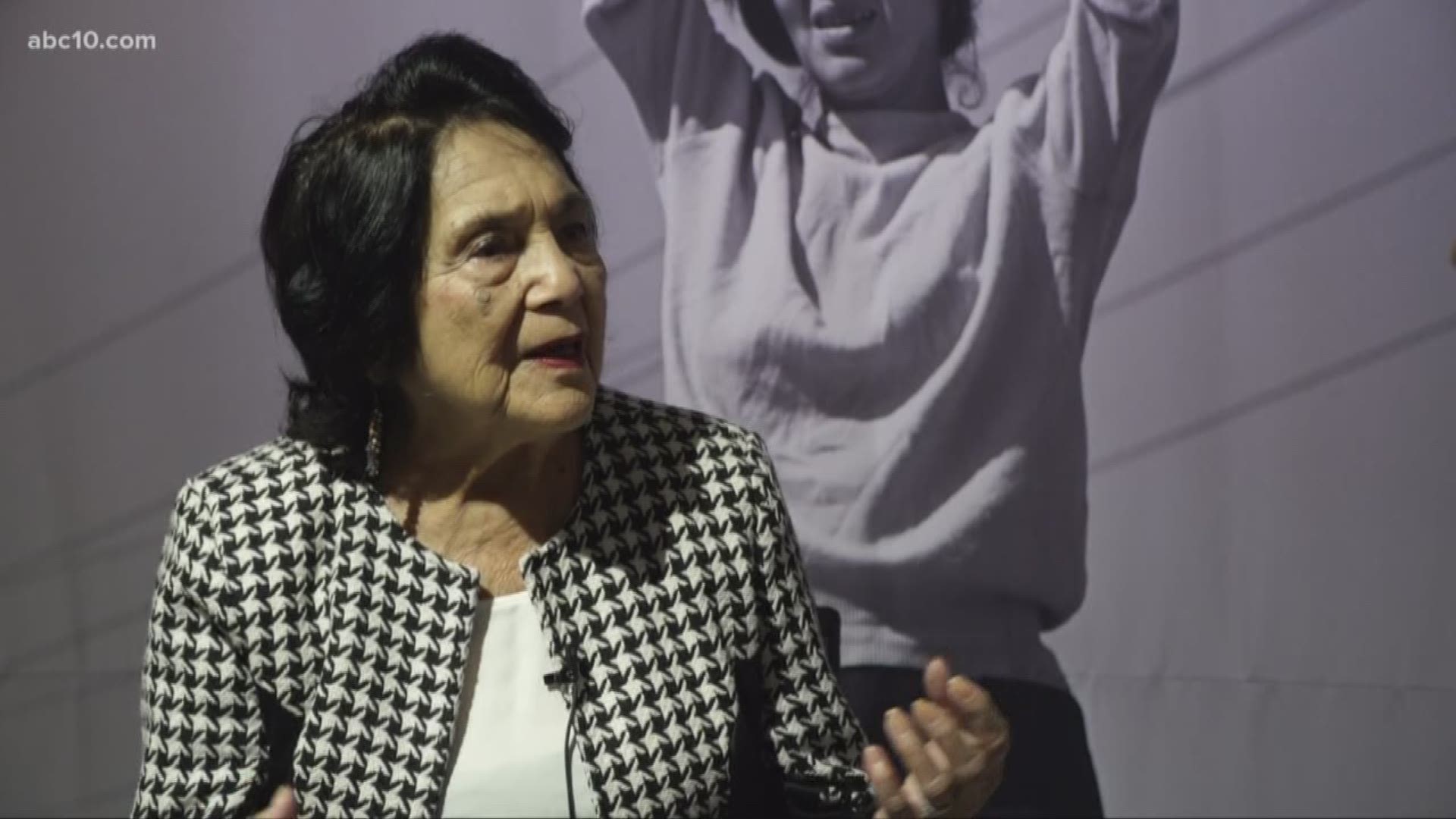

For Newsom, torpedoing Atkins’ signature legislation may have long-term political ripples. Support for him among some of California’s environmental advocates has soured, particularly because, they say, Newsom parroted opponents’ talking points that mischaracterized the impact of the bill.

“Is it going to be the same relationship, absolutely not. It’s naïve to think it would be,” said Kathryn Phillips, the California director of the Sierra Club, who called some of Newsom’s statements about the legislation “appalling.”

“Is this going to hurt the long-term relationship? You’re damn right it will,” she said.

Some groups will likely paint the governor — who sees himself as an environmental warrior — as a politician who, when it mattered, sided with big business and Donald Trump.

That’s not slander to the bill’s opponents, who, flush with success, have showered the governor with praise. But those same water and ag interests threatened to walk away from the voluntary water negotiations unless Newsom came out against the bill, and there’s no guarantee that wouldn’t happen again.

Kate Poole, a water lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group, said Newsom was “blackmailed” by the threats to leave the bargaining table.

“That’s not going to end with SB 1,” she said. “They’ve got him over a barrel.”

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.