It's been 50 years since the Detroit riots, but healing is hard to come by.

Social and legal equality are at the forefront of Detroit (***½ out of four; rated R; in select cities Friday, including New York, Detroit, Chicago, Atlanta and Los Angeles, in theaters nationwide Aug. 4), the latest film from Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty), who continues to take on some the most chilling chapters in American history.

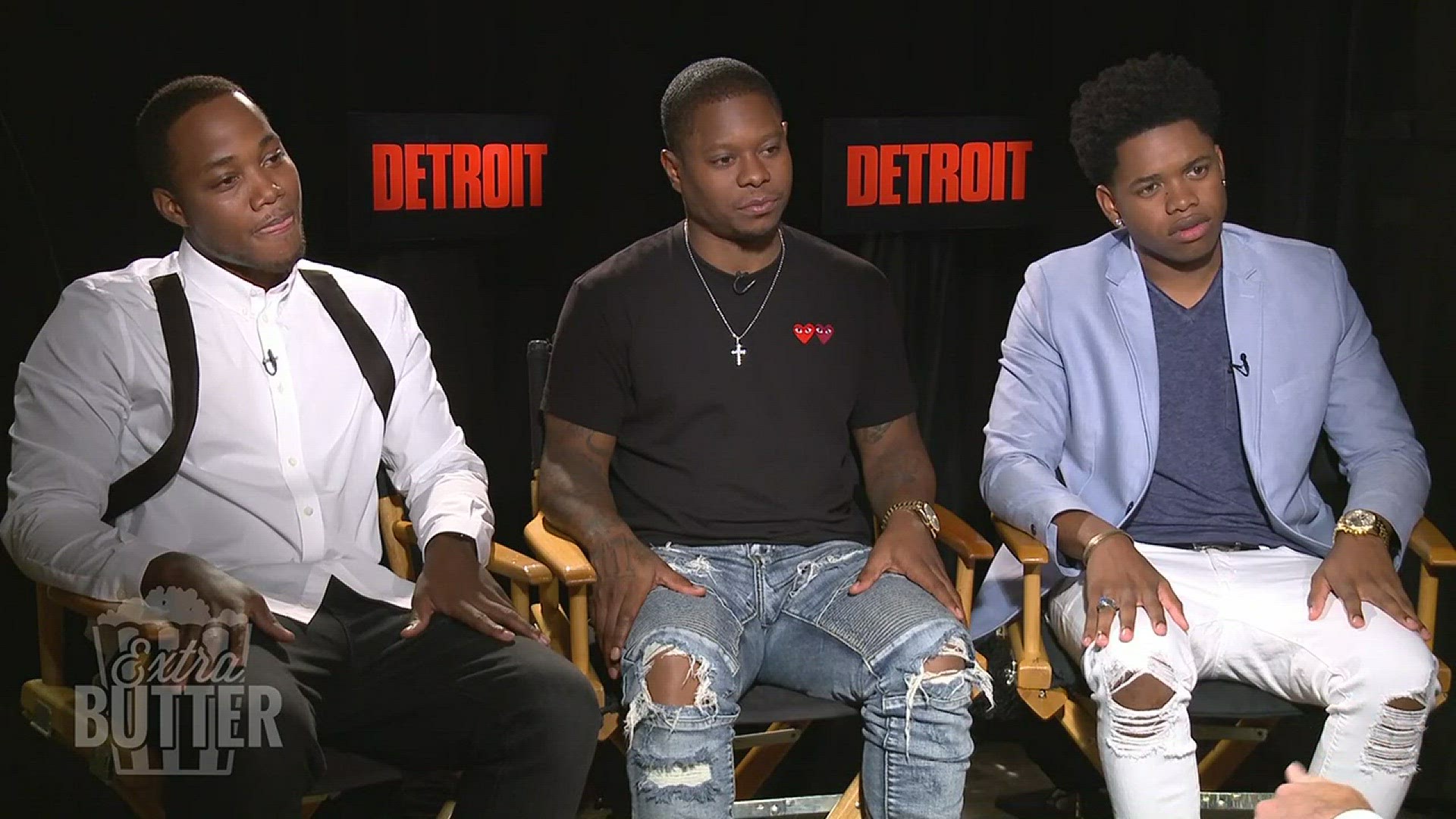

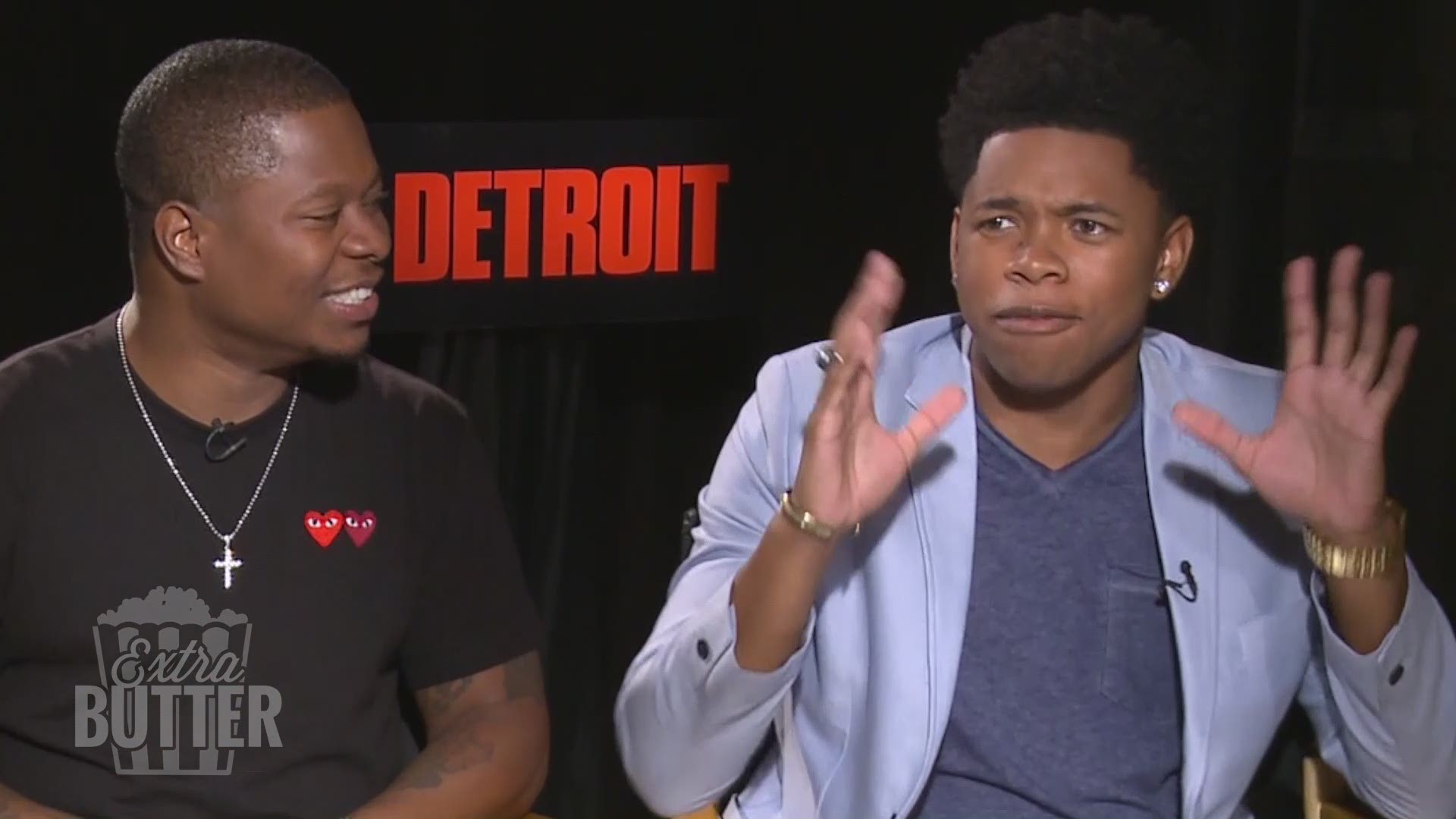

For Detroit, the director relies on a mostly unknown cast (save for Star Wars: The Force Awakens’ John Boyega and Avengers: Age of Ultron's Anthony Mackie) to tell the homegrown horror story of what happened at the Algiers Motel as riots choked Detroit's inner city in 1967.

Kathryn Bigelow brings her unflinching eye to a real-life night of terror in 'Detroit'

Police stormed the Algiers and viciously interrogated a group of young black guests and two white girls (Hannah Murray and Kaitlyn Dever), ultimately killing three unarmed teens.

In Zero Dark Thirty, Bigelow juxtaposed Jessica Chastain's nausea with the U.S. military's illegal torture techniques. In Detroit, as guests are bloodied in a hotel hallway lineup, there's no such counterbalance, creating a prolonged exercise in unchecked power. It's a stunning, if devastatingly effective achievement.

Political and civil tensions are set to a boil in the movie's opening scene, when police raid an unauthorized African-American club, marching their captors onto the streets. An angry crowd forms, and Molotov cocktails begin to fly.

Shot in cinema vérité style, Detroit seamlessly mixes real news footage with scripted scenes. The audience meets the central players, beginning with racist cop Philip Krauss (an exceedingly committed Will Poulter, playing a composite character), who shrugs when he's disciplined for gunning down a black man running away with two bags of groceries.

It’s impossible to take in the scene without seeing Trayvon Martin’s face. Or Michael Brown’s. Or Philando Castile’s.

As the city burns and tanks roll in, Boyega, playing steady security guard Melvin Dismukes, readies himself for the night's looting. Across town, aspiring Motown singer Larry Reed (newcomer Algee Smith in a stunning performance) and his friend Fred Temple (Jacob Latimore) take refuge in the Algiers after a gig is canceled, where $11 gets them a room to wait out the crisis with booze, tunes and girls.

It’s here where Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal largely rely on first-person accounts and found documents about what transpired in the Algiers, with a bit of creative license.

From a hotel room, prankster Carl Cooper (Jason Mitchell) shoots a blank from a starter pistol toward police staking out a street nearby. A riot squad and the National Guard descend on the tiny motel.

The next 40 minutes turn the Algiers into a lawless house of horrors. Led by the unhinged Krauss, police officers brutalize guests, accuse the women of prostituting for Mackie's Vietnam vet Robert Greene and enact a ruthless “death game,” pretending to shoot guests in closed-off rooms to force others to talk. Cops drop pocket knives by the hands of the dead, the implication clear.

Detroit is likely destined for the Oscar race, where Smith and Poulter could go head-to-head with best supporting actor nominations, if the film sustains itself through the long awards slog.

The film's unflinching gaze on a lawless night will likely be politicized, but calling Detroit anti-police misses the mark. The question Detroit begs is, in a democratic nation, to whom does the law apply?