Television and movies often depict the identification of bodies in dramatic scenes in morgues, usually involving drawing back a sheet to reveal the face of the deceased, often accompanied by the bereaved gasping and/or fainting in shock.

While it may have played out that way in days past, forensic science has largely supplanted this method.

“We try and do it scientifically, rather than visual,” said Kimberly Gin, spokesperson for the Sacramento County Coroner’s Office.

This week, as an autopsy was pending to find cause of death for a body found in the Feather River Sunday.

The Sutter County Sheriffs's Office have confirmed that the body found was that of missing 20-year-old college student Aly Yeoman.

A fisherman saw the body near the Live Oak Recreational Park boat launch, in Live Oak, according to a Sutter County Sheriff's Office report. However, the body had not been identified until Tuesday afternoon.

Alycia Yeoman's truck was left in an orchard in Live Oak before her disappearance more than a month ago.

Most unidentified bodies are identified by fingerprints, if the fingerprints are still intact. When they aren’t, examiners turn to dental records.

Depending on how recent the dental records are, a person’s teeth can positively identify him or her, especially if there is something unusual about the teeth or dental work done, Gin said.

The last resort is DNA.

Dental records and DNA are usually only practical if investigators have some idea of who they think the unidentified person was, and this is most likely when the person has been reported as missing. Gin stressed that a missing person’s report can be a crucial element in discovering identity.

The quickest way to identify a body is by fingerprint. Dental records can take longer, depending on how long it takes to locate and request them.

DNA testing typically takes the longest, Gin said. Although the state laboratory makes such cases a priority out of deference to families anxiously awaiting the results, it can take six to eight weeks for a routine case.

This also depends on cooperation from relatives of the missing person, Gin said. In some cases, people don’t want to give DNA samples out of distrust of government agencies, however, the county normally prevails.

Sometimes there are complications.

In the case of Joaquin Islas-Moreno, a man whose body was found in 1980 and not identified until last year, the original information given to investigators contained a wrong name. However, relatives of a missing man happened to find reconstruction sketches of the man on the county’s website, and thought it was him.

Fortunately, the county still had slides from the autopsy containing tiny samples of the man’s organs to test against a relative’s DNA sample, so they did not have to exhume the body.

Although the name didn’t match up, the DNA test did.

The family finally had an answer after 36 years.

The coroner’s office currently has 73 active ‘John Doe’ and ‘Jane Doe’ cases dating back to 1975. Investigators never give up on these cases, and continue to seek leads years or even decades later, Gin said.

Cases of teens and young adults can be challenging, because sometimes they aren’t reported as missing, and often have never been fingerprinted.

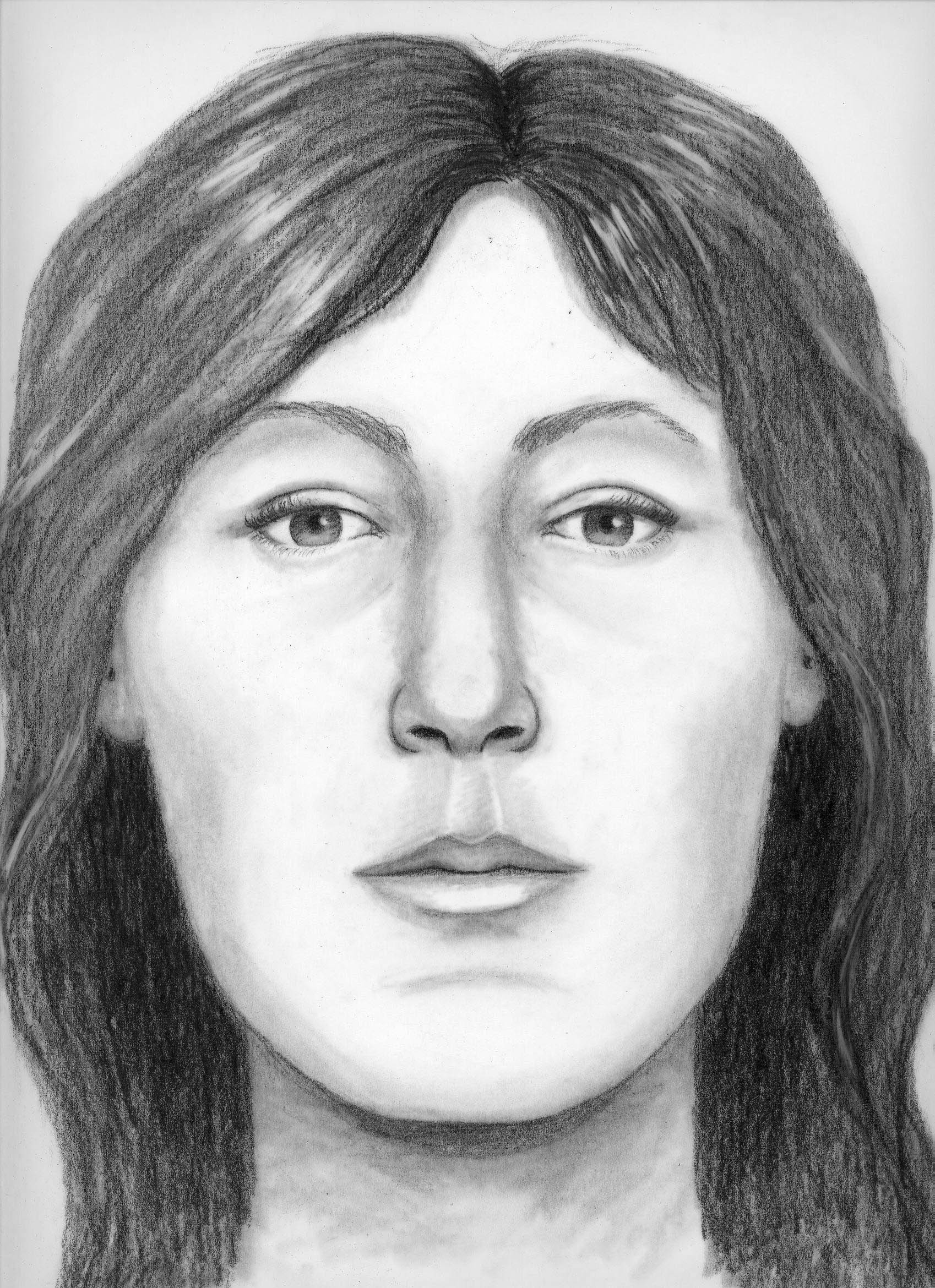

Investigators have worked hard to name a young woman who was found in a trash bin in 2001, Gin said. She might have been a runaway from another state, or a victim of trafficking or both, but they don’t have much to go on. Barring a relative or friend finding the reconstruction drawings online, chances are slim she will ever be named.

“It takes somebody just saying, ‘Hey, I think that might be…” Gin said.

County investigators welcome tips or leads on these John and Jane Does, who are buried in various cemeteries around the county.

“We’re always hopeful someone’s looking because they are missing someone and they give us a lead,” Gin said.