COLORADO, USA — The gas molecule known as ozone is harmful to humans if we breathe it in, but high in the stratosphere it protects us from being over exposed to the sun's ultraviolet radiation.

In 1985, scientists discovered that human-made chlorine was causing the ozone layer to vanish. It was problem that became known as the 'ozone hole'.

Just two years after scientific research linked human activity to the formation of the ozone hole, world leaders came together to ban chlorine-based refrigerants and other types of chlorine aerosols.

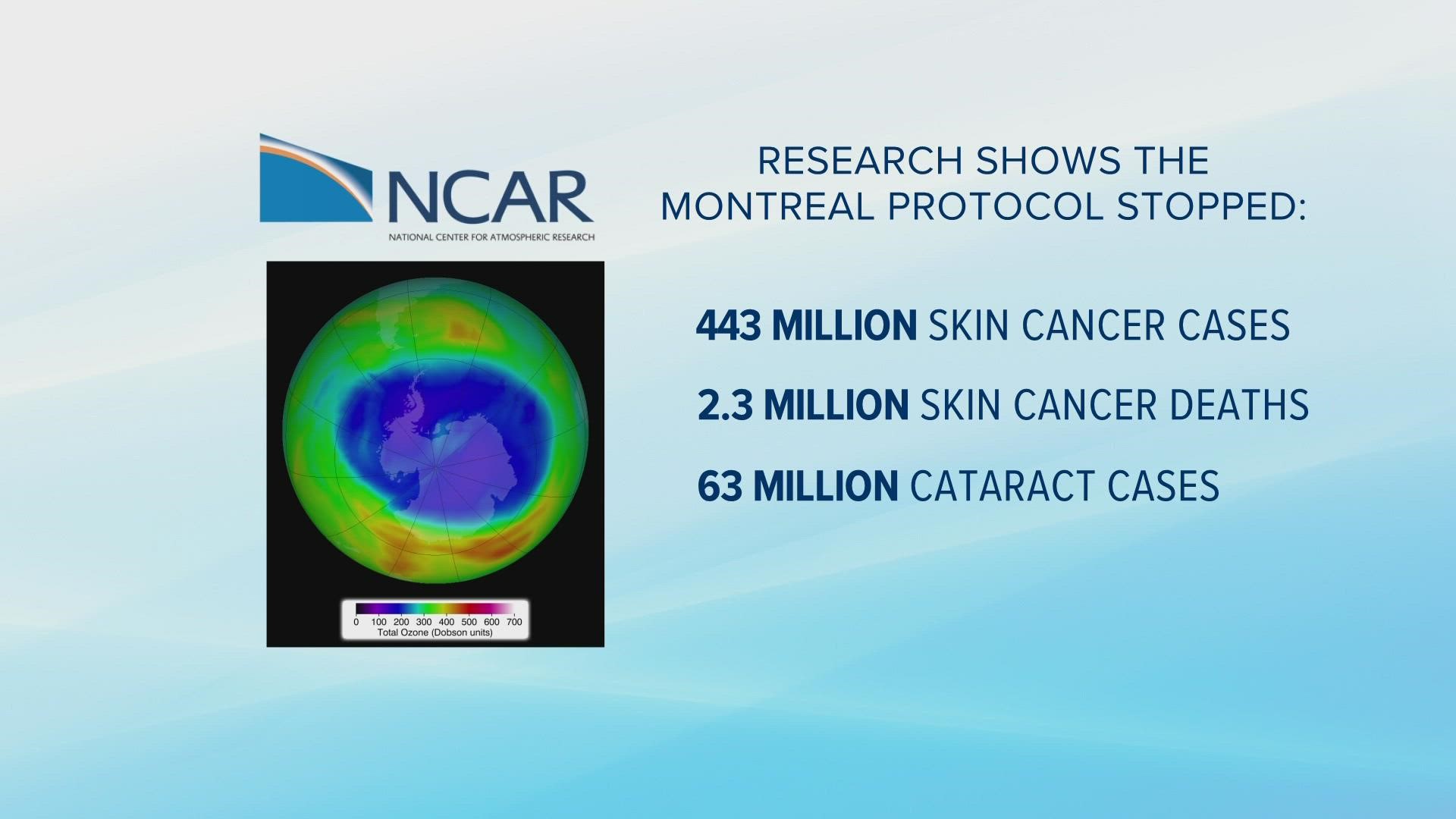

Now in October of 2021, the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) teamed up with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to publish new research about the health impacts of the Montreal Protocol.

The paper, which was published in ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, showed that the treaty has likely spared 443 million Americans from skin cancer, prevented 2.3 million skin cancer deaths, and 63 million cataract cases.

“Yes it’s a victory for science," said NCAR researcher Julia Lee-Taylor. "It’s a victory for the communication between science and the policy makers.”

Lee-Taylor and her team used computer modeling to simulate how UV radiation would have impacted Americans born from 1890 to the present day, along with census projections to include the population up to 2100.

They were able to make projections of the potential health impacts that would have occurred if the Montreal Protocol was not signed and the ozone hole was able to continue growing unchecked.

She said overall, the treaty prevented more than 99% of potential health impacts that would have otherwise occurred from ozone destruction.

Specifically the study showed that people born between 1900 and 2040 would have experienced heightened cases of skin cancer and cataracts, with the worst health outcomes affecting those born between about 1950 and 2000.

Lee-Taylor said after the ban, it took nearly 20 years to see a response in the atmosphere, but the ozone hole has been gradually repairing itself ever since.

“If we continue on the current trajectory of keeping the chlorine levels under control, we should be able to see the ozone layer go back to its pre-1980 levels by the mid-2040s, certainly by 2050,” she said.

Lee-Taylor said the results of her study validate the life-saving decisions made 34 years ago, and she hopes that success will resonate to other sciences like climate change.

“Well I have hope," she said. "The Montreal Protocol gives me a lot of hope that we can work together to find solutions.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Science & Weather