COPALIS BEACH, Wash. — The origin of what is feared could be the largest natural disaster in United States history lies in wait off the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

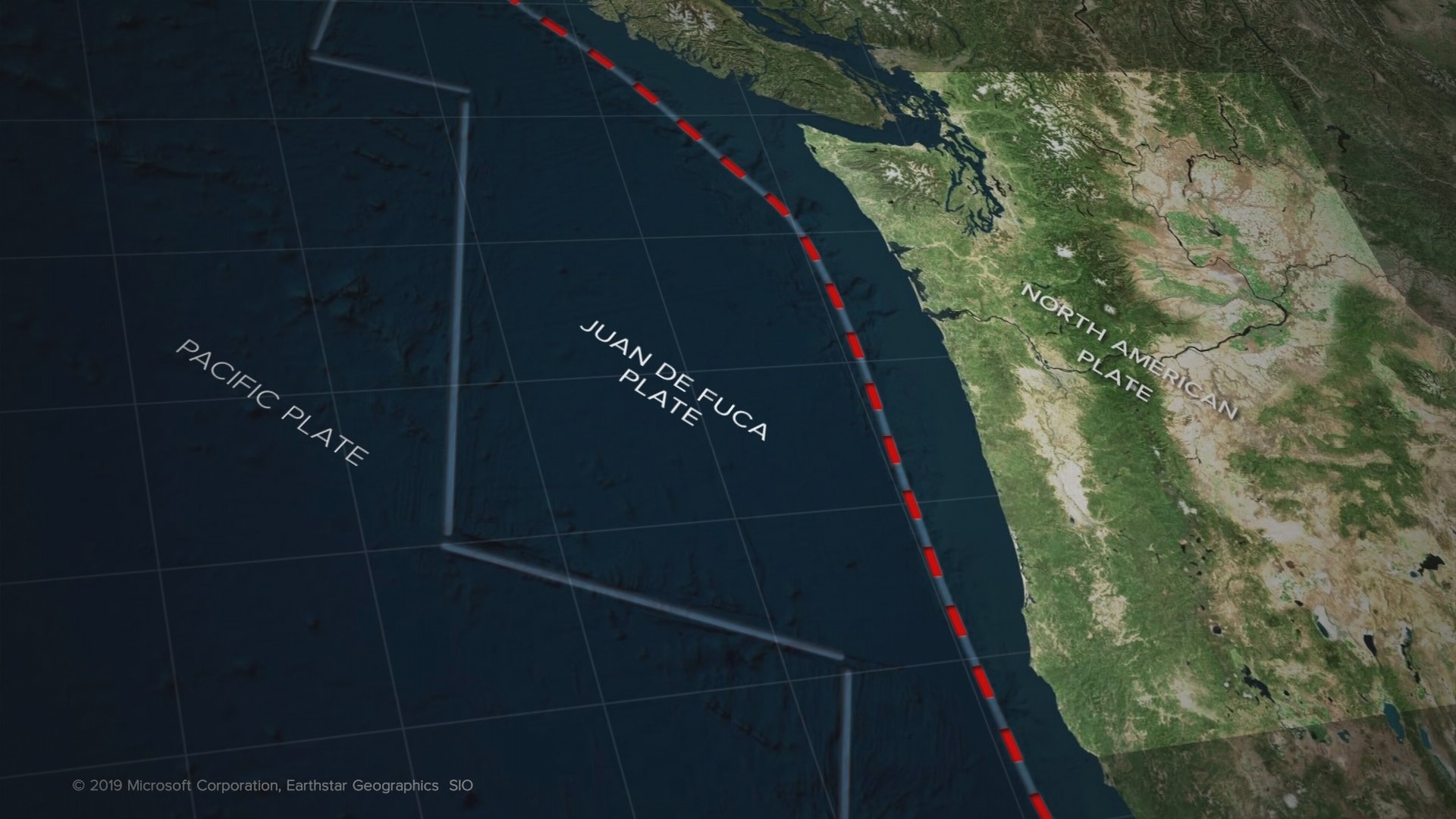

Scientists say a great earthquake – a magnitude 9 – could potentially strike at any time. The earthquake would follow the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a 600-plus-mile underwater fault running from off Cape Mendocino, Calif. past Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia.

The quake would also trigger a tsunami – a mirror image of the March 2011 magnitude 9 earthquake and tsunami in northeastern Japan that left nearly 16,000 dead and missing.

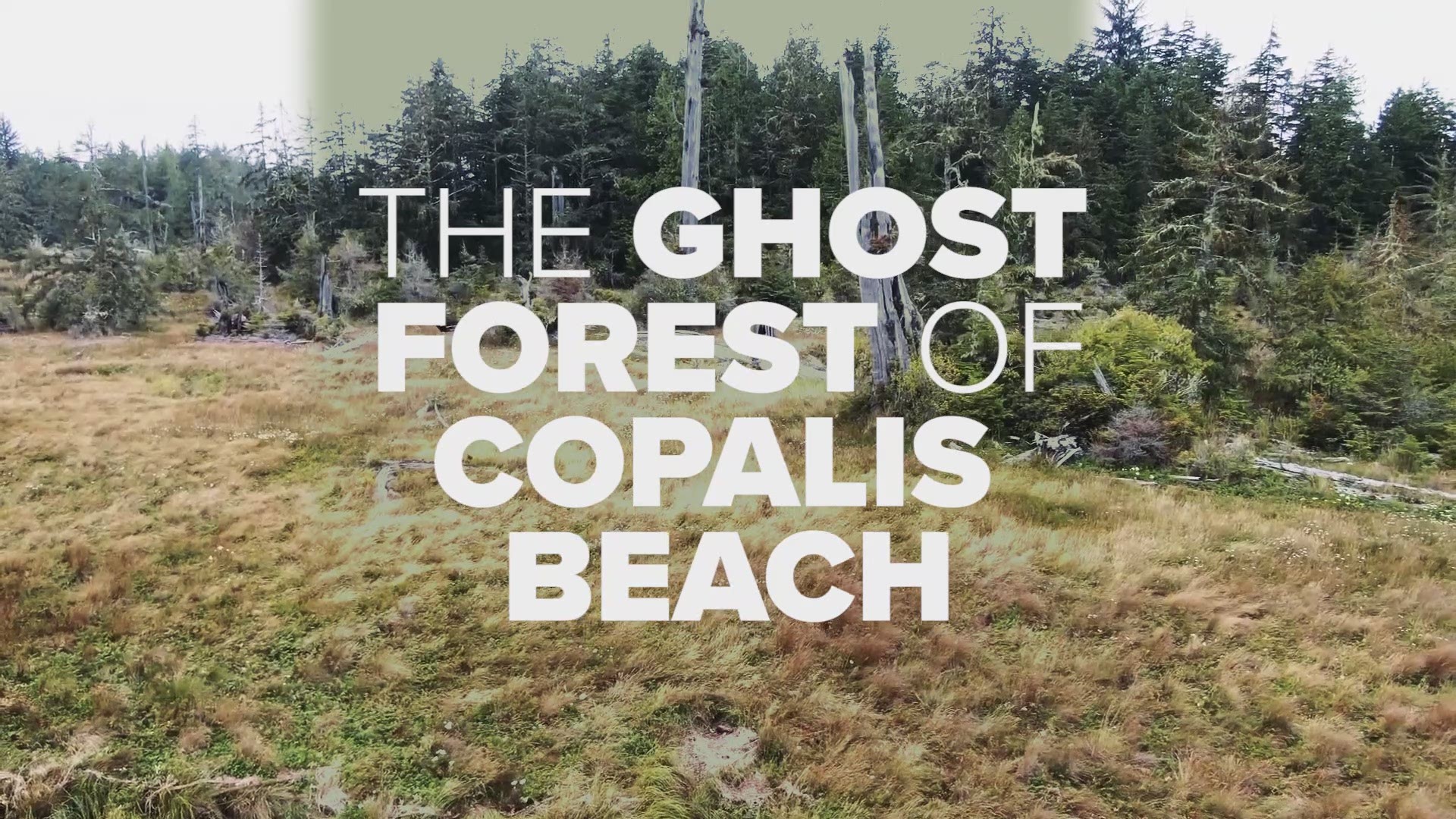

Tree-killing quake

The last quake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone occurred at 9 p.m. on January 26, 1700.

Why such a precise estimate from three centuries ago?

First, scientists measured tree rings near the Washington and Oregon coasts from multiple “ghost forests,” which are areas of dead trees that have been invaded by saltwater. Tree rings vary by season and conditions, such as dry years and wetter years. In correlating rings from surviving trees, it appears the trees killed by the quake were alive in 1699 but not 1700.

The specific hour was determined with the help of another tsunami that struck Japan at a similar time. Japan was hit with a tsunami seemingly out of the blue. It was called the “orphan tsunami,” because it was not associated with any earthquake activity in Japan. Scientists took the recorded time of the orphan tsunami and backtracked it by the 500 miles per hour of tsunami energy it takes to cross an ocean to calculate when it began.

A quake would have shaken the trees, but why did these die?

Scientists say the trees were killed when the land they were growing on suddenly dropped between six and eight feet, turning the land into a salt marsh. Coniferous trees can’t live in salt water.

Until the quake, the land was barely above sea level, but it was rising. The trees were able to grow on that slowly rising land for several centuries until the quake released pressure. The land dropped as pressure building between the North American tectonic plate and the Juan de Fuca plate, which was being forced under it, unlocked. The earthquake was released, relaxing centuries of built up tension. It lowered the outer coast, and also allowed it to move west, beginning the next cycle.

Case study: Discovery Bay

Carrie Garrison-Laney, a geologist and coastal hazards specialist with Washington Sea Grant, a non-profit affiliated with the University of Washington, has brought us to Discovery Bay near Port Townsend on Washington’s north coast. Discovery Bay, shaped like a large funnel with the open end pointed to the west, is the repository of tsunami evidence in the form of layers of mud at the bay’s shallow end. It’s interspersed with layers of sand pushed up by tsunami waves believed to be in excess of 30 feet high.

“This one has a radio carbon date that’s about 600 years old,” said Garrison-Laney as she pointed to a gray layer of sand in a mud bank along the coast, a sure sign from a previous great earthquake and tsunami. “And this one has a radio carbon date that suggests it’s from 1700.”

This past summer she found pockets of sand believed to have been driven in by the magnitude 9.2 Alaska earthquake of 1964.

But it’s the big Cascadia earthquakes that are suspected to have left the biggest impact, even though Discovery Bay is closer to populated Puget Sound than the outer coast where the fault lurks.

“Even though we’re further inland than the outer coast, the shaking was probably pretty strong here,” said Garrison-Laney. “That shaking could have set off landslides locally and submarine landslides. And then within about an hour and one half, the tsunami would have arrived.”

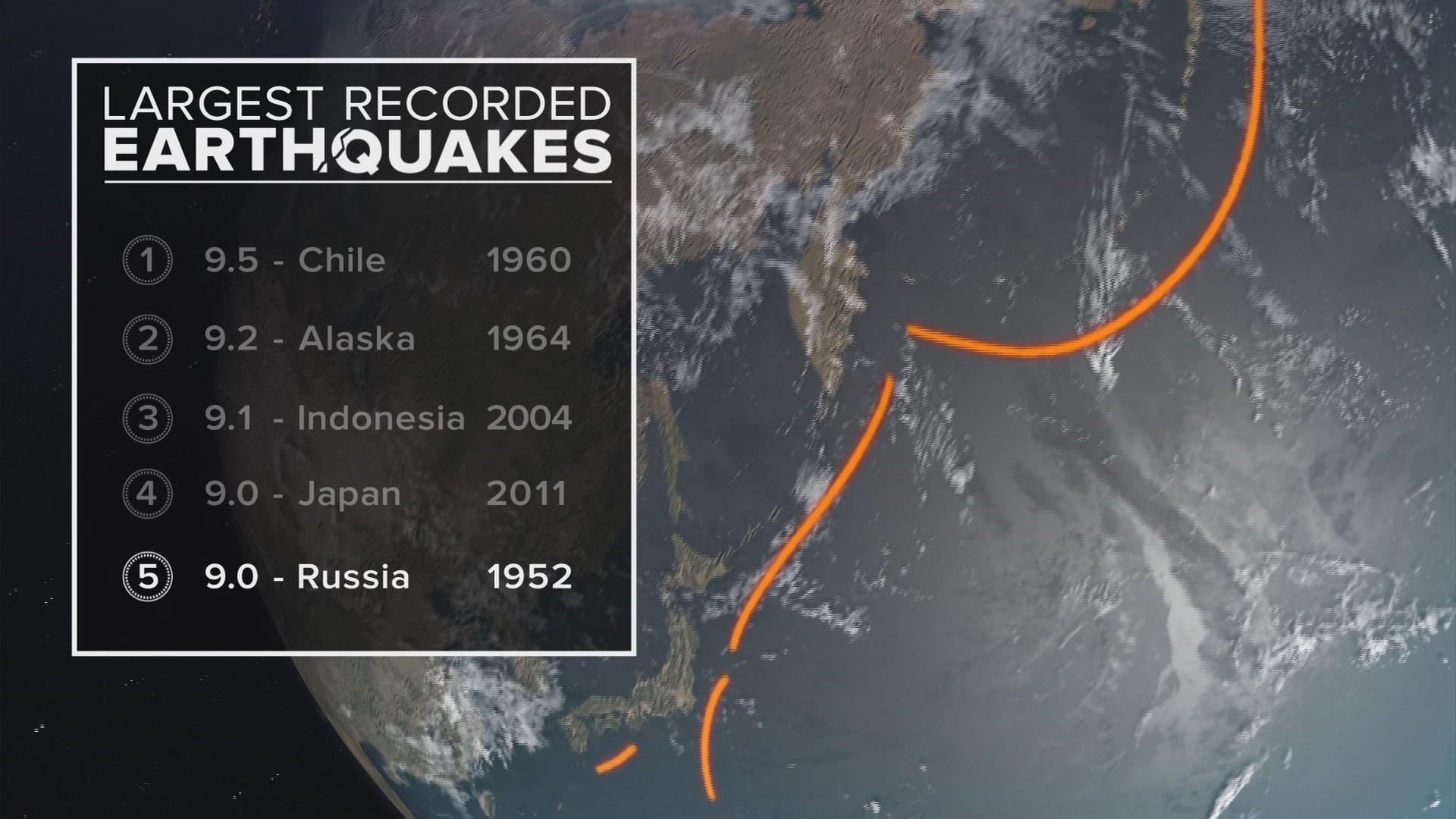

Pacific Rim impact

If this all seems like ancient history, consider this. The west coast of the U.S. sits on the Pacific Rim. The countries on the Pacific Rim not only share the world’s largest ocean, they share similar violence prone geologies. The five largest earthquakes in recorded history have happened on the Pacific Rim within the last 70 years, meaning within the lifetime of many of us.

- 1952: Magnitude 9 in eastern Russia

- 1960: Magnitude 9.5 in Chile

- 1964: Magnitude 9.2 in Alaska

- 2004: Magnitude 9.1 in Indonesia – this earthquake sent tsunami waves into the adjacent Indian Ocean and is estimated to have killed nearly a quarter million people

- 2011: Magnitude 9.1 in Japan – the Tohoku Earthquake killed nearly 16,000 people

That means the Cascadia Subduction Zone is the last major Pacific Rim fault zone to have remained quiet. The question is for how much longer?