DAVIS, Calif — The Design of Coffee class at the University of California, Davis is the first of its kind.

There is quite literally nowhere else in the world that is doing the type of caffeine-fueled research that is currently going on at the UC Davis Coffee Center and Undergraduate Coffee Lab.

That's really saying something, considering just how popular coffee—and espresso, and lattes, and specialty drinks—are in the world. Even at the number one university in the nation for agriculture, wine and viticulture tends to take center stage.

"Coffee has not had that," said Professor William Ristenpart, who began the Design of Coffee class with Professor Tonya Kuhl. "There's nowhere really in the country that has a focused, academic effort on coffee."

As such, researchers working with coffee find themselves examining 'coffee lore,' or things long observed in coffee, but never scientifically explained. For example, have you ever noticed how much better freshly-ground coffee beans taste when brewing a fresh cup of coffee?

There's a scientific reason for that, and it has everything to do with the "yummy, volatile flavor molecules," as Ristenpart calls them, that leak from the coffee bean once it is ground up.

Now, coffee lovers can express these well-known attributes of coffee with quantifiable data and scientific observation.

Between professors Ristenpart and Kuhl, both chemical engineers, coffee education at UC Davis has grown incredibly from when they first started teaching the Design of Coffee course as a freshman seminar in 2013.

"It's now one of the most popular courses on campus at UC Davis," Ristenpart said. "We have almost 2,000 students per year go through the Undergraduate Coffee Lab."

And then, of course, there is also the Coffee Center.

"When Tonya and I first got into this, we thought of it entirely as a pedagogical teaching exercise, but very quickly, when we rolled out the class in 2013, we started getting interest from the coffee industry because it turns out that coffee, as important as it is to the world economy, has been very understudied academically," Ristenpart said.

With generous investments from big industry names—Peet's, Probat, La Marzocco, just to name a few—an exciting new project is now underway: the UC Davis Coffee Center.

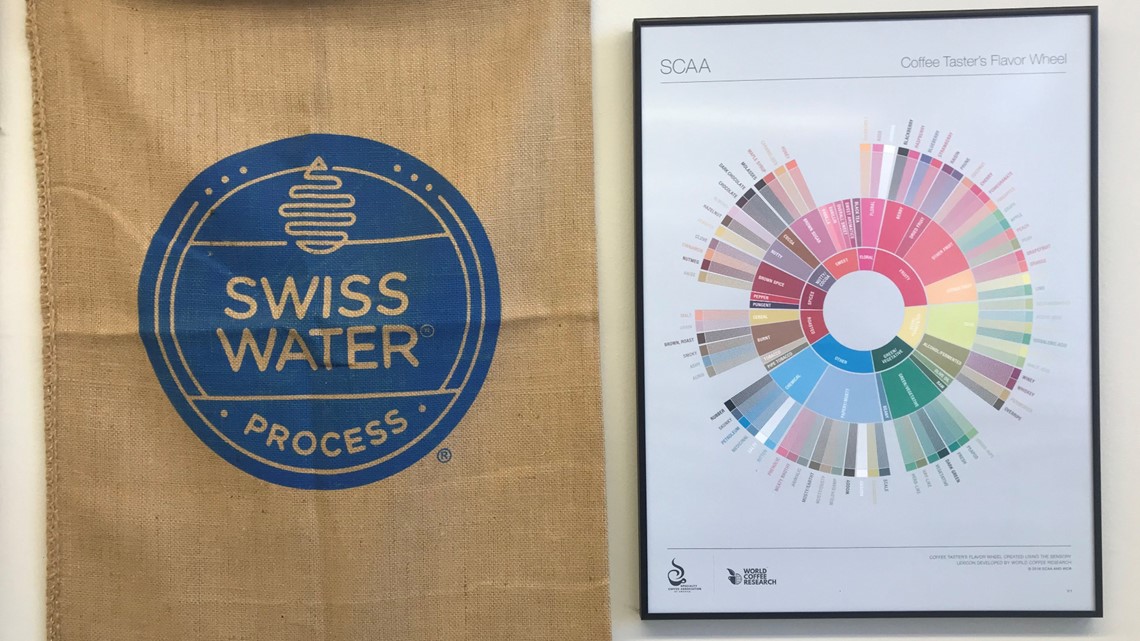

Design plans show a modest, but highly functional space. A bright lobby with a delicious espresso bar and large decal of the coffee sensory wheel promises an inviting, open space for students and researchers.

Ristenpart calls it the "nexus."

"We're taking...all the different expertise we have on campus, and focusing the intellectual fire power on coffee," Ristenpart said.

There are big plans for this building.

"We're going to have a brewing lab, a sensory lab, a chemical lab, all these different resources to help facilitate not only advanced coffee education, but also cutting edge research," Ristenpart said.

In the Coffee Center's pilot roastery, Ristenpart works with Head Roaster and Probat Roasting Fellow Juliet Han to create a curriculum focused solely on roasting coffee beans.

While the rest of the Coffee Center awaits renovation, Han fires up the Probat roasters.

"Coffee moves really quick here," Han said. "The majority of the coffee I roast is for research projects that we have going on. By late spring, we hope to sell our coffee to the bookstore on campus that will be roasted by students and packed by students as a way to bring income into the Coffee Center."

Han is also developing continuing education courses, including a home roasting course.

"It's easier now than ever to roast your coffee at home and Juliet is an expert on that, so we're really delighted to be working on that," Ristenpart said.

Undergraduate students help with the experimentation, working with small batches and dipping into brew processes. Three such students, fourth-year chemical engineering major Ashley Thomspon, fourth-year chemical engineering major Reece Guyon, and third-year food science major Lik Xian Lim, already have an incredible grasp on the roasting process.

The team of three knock out several batches of medium roast coffee, taking about nine minutes per batch on a small Loring roaster.

Guyon pours green beans into the roaster for a dark blend. When a couple fall to the floor, Xian Lim quickly gathers them up and adds them to the Loring. While it looks as though he is just being meticulous, Thompson explains that even the smallest changes in weight could produce faulty data.

"Every gram counts," Thompson said.

All three undergraduates work in synchronicity, comfortably tinkering with the machine and comparing the results from the previous roasts. Han doesn't even need to step in, confident that the students know what to do.

"This has kind of been a dream job," Han said. "I'm at this really interesting intersection of academia and the coffee industry. I'm in this really amazing, unique position to be an ambassador to the coffee industry world, people, and also to bring a little bit the industry to students."

Where the Coffee Center is somewhat quiet, the Undergraduate Coffee Lab on the other side of campus is busy, noisy with the sound of grinders and roasters.

In the lab, students learn how to roast, brew, and taste coffee—all with a focus on the science that goes into making the perfect cup of joe. By the end of the quarter, Professors Ristenpart and Kuhl hold a competition to see who can design the best-tasting cup of coffee using the least amount of energy.

"That's a fun way of teaching classic, engineering optimization principle," Ristenpart said. "You're trying to maximize something [in this case, how good it tastes], while minimizing something else [in this case, how much energy you use to make it]."

Their final contest score is a ratio of a blind-taste score divided by the kilowatt hours of electrical energy used.

"Sometimes groups will make the most delicious coffee, but they've used too much energy, and so they don't win the overall contest," Ristenpart said.

On this typical lab day, groups of two and three grind their way through measurements and calculations. The smell of roasting coffee quickly gets replaced by brewing coffee.

Kuhl called Ristenpart over to a group of two students, who looked on proudly as the professor sipped their fresh brew.

"They've made an Ethiopian the way Ethiopian is meant to be made," Kuhl told Ristenpart, so he poured himself a sample.

When Kuhl says 'Ethiopian,' she's referring to the origin of the beans. In different countries, coffee fruit is cured in different ways to extract unique flavors.

Ethiopian coffee cherries are dried in the sun, like raisins. Then, the fruit is scraped away, the green beans roasted right in the Coffee Lab. As such, Ethiopian blends are characteristically fruity, a product of this curing process.

The sensory experience is important. The professors are hoping to expand upon tasting and aroma in their Design of Coffee class.

With upgrades on the horizon for the Coffee Center, plans are also set in motion for sensory tasting labs. Though the program currently uses sensory labs at the Robert Mondavi Institute, the Coffee Center will have a design that is specifically ideal for tasting coffee.

While coffee aficionados will have to wait for UC Davis' nexus of coffee exploration to be fully functional, rest assured that pioneering professors like Ristenpart and Kuhl are carefully considering the ultimate design of coffee.

The coffee scene in Sacramento has been on the rise, so coffee science and research is more important than ever. Now, with Blue Bottle Coffee having recently moved its West Coast roasting facilities to West Sacramento, coffee in the Greater Sacramento region is seeing its heyday.

Though Han has only lived in Sacramento for a short time, she notes the exceptional coffee selection.

"Everyone describes Sacramento to me as this sleepy town, but there's a ton of coffee places that you can go to. You can probably spend two days doing a coffee crawl with some fantastic places where you can also get food," said Han.

As such, it was only natural that UC Davis would take on the scientific angle to coffee.

"Historically, academia has focused much attention on coffee just for the simple reason that coffee's not grown to any major extent anywhere in the continental United States," Ristenpart said. "That’s starting to change…But, more importantly, given how important coffee is, I feel that academia needs to play a bigger role in studying what in some sense is kind of the world's most important beverage. It not only powers people here, but also provides a way of living, or a way of supporting, about a 100 million people around the world. Many people in developing countries, whose livelihood depends on coffee."

RELATED:

FOR NEWS IN YOUR COMMUNITY, DOWNLOAD THE ABC10 APP:

►Stay In the Know! Sign up now for ABC10's Daily Blend Newsletter