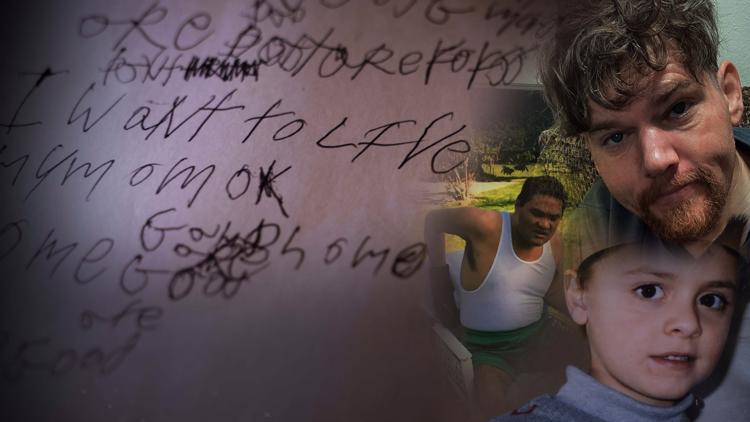

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — ABC10 has been investigating California’s conservatorship system for two years.

In season one, we dug into general conservatorships in a five-part investigative series. In our second five-part series, we focused on limited conservatorships for those with disabilities.

This complex system is filled with complicated legal processes, jargon and questionable practices.

Here at ABC10, we stand for you, and we wanted to ensure anyone watching our reporting could thoroughly understand this complicated system. In the aftermath of our reporting, we want to make sure viewers are connected to resources that could help anyone navigate a conservatorship or get involved to push for change.

With the help of system insiders, experts and advocates, we have gathered the information below for the past two years while investigating conservatorships and compiled the following resources for you.

Below you’ll find an index of terminology, the agencies, experts and those impacted by this system that we featured in season two of our investigation, The Price of Care: Taken by the State.

We also provided contact information to the many agencies entrusted with this system to reach out, and provide feedback, and any concerns sparked from our investigation.

Terminology:

Conservatorship: Known as guardianship in states outside California, a conservatorship is a legal arrangement where someone assumes rights and responsibilities over another person who is unable to care for themselves. Conservatorships are a tool to help protect and provide assistance to our most vulnerable populations. Conservatorships must be approved through the probate court. While there are different types of conservatorships in California, limited and general, both have two main ways of taking control - when someone assumes responsibility over another person’s finances, it’s called “conservatorship of the estate.” If someone takes responsibility for an individual’s personal life, decisions and health choices it’s known as “conservatorship of the person.” Often, conservatorship over the person and their estate occur together and are very powerful as the person acting as a conservator can make all choices for the person who is conserved.

General conservatorship: A general conservatorship strips someone completely of their civil rights and gives them to another person. These types of conservatorships are often for the elderly or those with dementia. Conservators in general conservatorships are often family members or professional fiduciaries.

Limited conservatorships: A limited conservatorship gives a conservator specific authority over another person’s life, i.e. “the conservatee.” These conservatorships are specifically tailored to those with disabilities and are called “limited” because they’re supposed to be unique to the individual being conserved. The conservatorship is supposed to limit the powers and civil rights taken from a person to only seven specific items they need assistance with. Conservators in limited conservatorships are often parents, however, the Department of Developmental Services can be appointed as conservators in some cases where other potential conservators are “deemed inappropriate.”

7 powers of limited conservatorship:

Power over the conservatee’s residence or place of living

Access to the conservatee’s confidential records

Give or withhold consent over the conservatee’s marriage

The ability to enter into contracts on behalf of the conservatee

Power over medical decisions

Power over educational decisions

Power over the conservatee’s social and sexual relationships

Lanterman Act: Passed in 1969, this California law ensures people with disabilities have equal rights. To uphold this law, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) was established as a service system to meet the individual needs of Californians with disabilities. This state agency oversees regional centers which directly provide services to people with disabilities as well as their families. The Lanterman Act is codified in the California Welfare and Institutions Code.

Service coordinator: Service coordinators play an important role in each regional center as they have “cases” or people with disabilities assigned to them. The coordinators are entrusted to conduct an Individualized Program Plan (IPP) that’s unique to the individual. With their IPP plan, the person can get specific services they need that help enable them.

Regional Center Assessment: When a limited conservatorship is petitioned for in probate court, an assessment must be done by the proposed conservatee’s regional center. Service coordinators are responsible for doing this assessment, which is an evaluation of the person that may be conserved. The assessment evaluates the person’s specific needs, and capacity and recommends which of the seven powers should be taken and given to a conservator. It also includes an overall recommendation of whether or not the conservatorship is appointed. The assessment goes to a probate court judge to help them decide whether or not the conservatorship petition should be approved.

Petition: This is the first legal step in conservatorship proceedings. A petition is a legal request, filed in court, to do something. When a conservatorship petition is filed with the probate court, it’s requesting the judicial action of starting conservatorship proceedings, which would lead to the approval of the conservatorship.

Court-appointed attorney: After a conservatorship petition is filed, California law requires the court to appoint/assign a lawyer for the person that may be conserved. This attorney is supposed to be a third party, stand for what the individual wants - like if they want to be conserved or not - and represent their voice and desires in a court of law.

Court investigator: Another action required after a conservatorship petition is filed is for an investigator from the court conduct a review of the person being conserved and the circumstances of their life. Their investigation findings are submitted to the court for the judge to review. If a conservatorship is appointed, the court investigator is also supposed to do annual or bi-annual check-ins of the conserved individual.

Visitation: For general conservatorships and limited conservatorships that have power over social and sexual contacts, restrictions over who the conserved person can and cannot see can be implemented. Many conservatorships we reviewed in our investigation had “visitation,” of loved ones, where family members had to get approval from the conservator and abide by a strict time frame and setting they were allowed to visit the conserved individual within.

Agencies/Organizations:

Department of Developmental Services (DDS): This is the overarching state agency responsible, by law, for overseeing the coordination and delivery of services and support to 400,000-plus (by 2023) Californians with developmental disabilities. DDS has a $12-billion+ budget funded by tax-payers to execute their responsibilities and ensure Californians with disabilities “have the opportunity to make choices and lead independent, productive lives as members of their communities in the least restrictive setting possible.” DDS also serves as a conservator to 400+ individuals.

Regional Centers: There are 21 regional centers throughout the Golden State that execute DDS’ responsibilities of ensuring people with disabilities have equal opportunities. These centers provide an array of services from arranging transportation to speech therapy to adult daycare classes to in-home caregiving.

Probate Court: The probate branch of court falls under each county’s superior court. This segment of the judicial system primarily handles matters such as wills, estates and conservatorships.

California Attorney General: As the state’s chief law officer, the California Attorney General is responsible for ensuring the laws of the state are enforced and safeguarding Californians from harm. This state entity has three main legal services divisions to uphold these responsibilities: Division of Civil Law, Division of Criminal Law, and Division of Public Rights. The California Attorney General is also responsible for representing state agencies and officials in a court of law.

Disability Rights California (DRC): This non-profit agency is designated under federal law to protect and advocate for the rights of Californians with disabilities. The organization has a number of programs and branches including litigation, legal representation, advocacy services, investigations and public policy and provides information to those with disabilities.

DRC Office of Clients Rights Advocacy (OCRA): This is a branch within Disability Rights California funded by the Department of Developmental Services, OCRA was created in the late nineties by the state legislature for “independent client rights advocacy by people who are not employed by regional centers (or) the Department of Developmental Services.” OCRA has at least one “advocate” assigned to support the clients of each of California’s 21 regional centers.

California Auditor: The California Auditor’s Office is our state’s “in-house watchdog” that’s independent of the executive branch and legislative control. Their work primarily comes from the legislature by joint way of the legislative audit committee. This state agency conducts a variety of audits including financial audits, compliance audits, performance audits and audits mandated by state law. The auditor’s goal is to determine whether or not government agencies are effective in fulfilling their missions and compiling with the law.

Spectrum Institute: A non-profit organization founded in 1987 by attorney Tom Coleman. The organization engages in research projects and educational programs on a wide range of human rights issues involving adults with mental or developmental disabilities. Spectrum Institute has published a number of detailed articles on how and why California’s conservatorship system is broken as well as solutions and steps to reform it.

Disability Voices United: A statewide organization directed by and for individuals with disabilities and their families that focuses on advocating for “choice and control, equity and accountability and meaningful outcomes.”

TASH: An “international leader in disability advocacy” founded in 1975, TASH advocates for human rights and inclusion for people with significant disabilities and support needs.

Free Britney: Sparked by the conservatorship of Britney Spears, the Free Britney movement has stood to ensure the superstar was released from her conservatorship and received justice for mistreatment. The movement is credited for both putting pressure on the judicial process in getting Spears free from conservatorship as well as transitioning to a civil rights movement for all those under conservatorship.

Association of Regional Center Agencies (ARCA): As the representative and “trade union” for California’s 21 regional centers, the Association of Regional Center Agencies’ mission is to promote and advance regional centers in upholding their duties designated by DDS and the Lanterman Act.

Adult Protective Services: Each California county has an Adult Protective Services (APS) division to help elder, dependent or vulnerable adults who are unable to meet their own needs. APS is entrusted to conduct investigations/reviews and work with law enforcement agencies to protect adults who need their services.

Contact information:

Department of Developmental Services:

Physical Address: 1215 O Street, Sacramento, California 95814

Mailing Address: P.O. Box 944202, Sacramento, California 94244-2020

Phone number: 916-654-1690

General Information line: 833-421-0061, TTY: 711

Nancy Bargmann, DDS Director:

- Email: Nancy.Bargmann@dds.ca.gov

Maria Nunez, DDS Conservatorship Liaison:

- Email: Maria.Nunez@dds.ca.gov

- Phone: 916-639-4724

- Office Phone: 951-554-1080

Brian Winfield, DDS Chief Deputy Director of Program Services:

- Email: brian.winfield@dds.ca.gov

- Phone: 916-654-1569

California Department of Health and Human Services

Physical Address: 1600 9th Street #460, Sacramento, California 95814

Phone number: 916-654-3454

Dr. Mark Ghaly, California Health and Human Services Secretary

- Email: mark.ghaly@chhs.ca.gov

California Attorney General

Physical Address: 1300 I Street, Sacramento, California 95814

Mailing Address: P.O. Box 944255, Sacramento, California 94244-2550

Phone number: 916-445-9555

Judicial Council of California

Physical Address: 455 Golden Gate Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94102

Phone number: 415-865-4200

Cathal Conneely, Public Information Officer

- Email: cathal.conneely@jud.ca.gov

- Phone: 800-900-5980

Disability Rights California

Physical Address: 1831 K Street, Sacramento, CA 95811-4114

Phone number: 916-504-5800

Disability Rights California OCRA:

Northern California Office: 1-800-390-7032

Southern California Office: 1-866-833-6712

Regional Centers:

California State Auditor:

Physical Address: 621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200, Sacramento, California 95814

Phone: 916-445-0255

Whistleblower Hotline: 800-952-5665

File a complaint with the California Auditor’s office by clicking here, by calling the whistleblower hotline above or mailing your complaint to: Investigations California State Auditor, P.O. Box 1019, Sacramento, CA 95812

Legislative Contact: 916-45-0255

Accessibility Contact: 916-445-0255

Your Elected Leaders:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Your Questions Answered

Can the California conservatorship system be reformed? How can someone create change? What if you’re considering a conservatorship - or fighting one? We tackle all these questions with attorney, expert and advocate Tom Coleman, Founder of Spectrum Institute. Here’s our full Q&A:

Question: What’s your take on AB 1663? Do you think it’s going to help reform California’s conservatorship system?

Coleman: “Well, it has great potential. Right now, the bill is on Governor Newsom’s desk waiting for his signature. I have every reason to believe he’ll sign it. There was no opposition to it in the legislature. What AB 1663 does is really promotes all alternatives to conservatorship, powers of attorney, trusts, supported decision making agreements. The bill encourages courts, lawyers and everybody in this system to try and use alternatives, but the only way it’s going to work is if it’s properly funded. It takes time to explore those options. It takes time for the courts and the lawyers and for capacity assessment experts and others. So, there’s going to have to be additional funding to make it work and that’s something the legislature is going to have to do; millions of dollars will have to go into this… or this will just be another interesting policy that makes no change at all. The second thing is that public defenders and court-appointed attorneys need to push the system to make AB 1663 work. In order for that to happen, the county supervisors are going to have to give more money to these attorneys to put in more time to make it happen. So, it always – unfortunately - comes down to money but AB 1663 has great potential.”

Question: The response to our investigation, The Price of Care: Taken by the State, has been overwhelming. For people who’ve watched and want to get involved in creating change, what can they do?

Coleman: “Knowledge is power. I’d suggest that people who want to get involved learn about the flaws in this system and the potential solutions. They can do that by going to our website, SpectrumInstitute.org, and right there on the homepage we have an article that identifies everything that is wrong and all the solutions that could be implemented to fix things. Learn those flaws and fixes – and then you know what? Pick one. You don’t have to pick everything – pick one of them that somehow resonates with you, then start taking action on it, start taking action steps and keep working on it until you see some progress. Then maybe joining together with others, maybe on one particular issue that you’re going to work on. If we have enough people joining in and picking a problem area and working on it and we all work together in harmony for the next few years, we’ll see some additional changes. There is a role for everyone.”

Question: For people who are dealing with a conservatorship right now and fighting it – what advice do you have for them?

Coleman: “Well, I’ve got to say my heart goes out to them because once you’re in that process, it’s almost like quicksand and you can’t get out. The system is so resistant and stubborn to change that people just get so frustrated and feel there’s nothing they can do. So, I would say that read AB 1663 and see if there’s some aspect of it that pertains to your case. Because when there’s a change in the law, that’s the opportunity for you to go back to the judge with a motion or petition to terminate the proceeding in favor of another alternative or to seek a modification on loosening some of the restrictions on your loved one. So, use this new opportunity, it’ll go into effect in Jan. 1, 2023. Between now and January, study the law and see what can apply to your case, then come January, hopefully the courts will be flooded with petitions for modifications and changes. So that would be my suggestion – move forward under AB 1663.”

Question: What do you think it’s going to take to really reform and change California’s conservatorship system?

Coleman: “I always call it, ‘Mission: Almost Impossible,’ because the system and all aspects of it are so resistant to change and are so stubborn, but I identified five pressure points that, if these agencies or officials took action, there could be tremendous progress made in reform.”

(1) “First is the Secretary of the Health and Human Services (HHS) agency – they oversee the Department of Developmental Services (DDS). The director is Mark Ghaly. People should be asking him to have HHS do oversight of the policies and practices of the Department of Developmental Services with respect to probate conservatorships to make sure that those policies and practices are ensuring quality of services and access to justice.”

(2) “Second is going to Governor Newsom. Asking him to appoint what I’m calling a ‘Conservatorship Czar.’ Right now, there’s nobody in charge of the system – it’s fragmented, it’s de-centralized – everybody points to everybody else and so on. There needs to be one person that will do some oversight of the entire system and the aspects of it. The governor should give some funding to this czar, and he or she can create an inter-agency task force to take a look at all aspects. Then, (the czar should make) recommendations to the governor in the next budget as to what funding and what controls need to go in to make this system work. It comes down to money.”

(3) “Third is what I’m calling a census and inventory. Right now, the judicial branch is supposed to be providing protection to everybody who is in a conservatorship. There could be as many as 80,000 people currently in a conservatorship, but the judicial branch and the California Chief Justice doesn’t even know how many people they’re supposedly protecting. They’re supposed to be protecting assets of the people. They don’t know how many billions of dollars the courts are protecting, so what type of a crazy system is that? Where the people who’re doing the protecting don’t even know who they’re protecting or how much money they’re protecting. The new Chief Justice, Patricia Guerrero, is coming into office, and if she’s confirmed by the voters then in January, people should be asking her through the Judicial Council to direct all 58 superior courts to conduct a census of people in conservatorships and an inventory of assets – that’s a good starting point.

(4) “The next one is directed to the California Attorney General, Robert Bonta. The attorney general is supposed to be the chief law enforcement officer of the state of civil rights laws. He’s supposed to be enforcing this, but he doesn’t because he’s too busy protecting the state agencies and officials that are violating the law. So, I think that he has another role, and that’s the he should convene a civil rights summit on probate conservatorship and bring together law enforcement, civil rights enforcement agencies and non-profits that work in enforcing civil rights laws to a summit in which to identify ways in which the state can better protect the rights of probate conservatees. He can do that without any conflict of interest in his other role of defending these agencies.”

(5) “Finally, it’s having grand jury’s probate the system at the local level. Alameda County did this and issued a report this year. I believe another county grand jury is going to issue a report at the end of the year, so people in their local community should be asking their civil grand juries to investigate the county’s role in the conservatorship system. Then the grand jury can then make recommendations on what the county should be doing to improve their role in the conservatorship system.

(6) “And there’s one that just came to my mind as I was watching your interview with the California State Auditor – and that is the state auditor should audit two or three counties as far as the probate court. The courts are always escaping review or analysis or audits or whatever. The state auditor should look at the Los Angeles County Superior Court and maybe the Alameda County Superior Court and maybe one other smaller one and look at all aspects of what the court is doing – are they obeying the law or not? Are there short cuts? What needs to be done to bring them into compliance with the law? So, those are my suggestions to truly make a difference as we move forward.”

Question: For those who are considering a conservatorship for a family member, whether that be someone with a disability or an elderly individual, what’s your message for them?

Coleman: “Be very cautious. Move slowly. Consider all alternatives other than filing that petition because once you file the petition, you’re stuck in quicksand and you may later regret it like many people do who thought they were doing the right thing. Check out a Power of Attorney for Healthcare, a trust, a supported-decision-making arrangement. Especially after Jan. 1, 2023 when the state law is encouraging and promoting alternatives – try that approach. There are some cases where really a conservatorship is in order and you may have to file one; if somebody is being abused, if somebody already has a power of attorney that’s taking advantage of it or if the person is being subjected to undue influence - giving money away. If you can’t get Adult Protective Services or law enforcement agencies to intervene to stop the abuse or the exploitation, then your only recourse may be a conservatorship and then of course, file one. But be cautious.”

Question: It’s important to note, conservatorships are meant to protect and help people who cannot care for themselves. Overall, what are your thoughts on conservatorships? Do you think it’s a good thing if implemented well?

Coleman: “If it’s implemented well and if the law is followed – including it being a last resort, that you’ve exhausted all other alternatives and those other alternatives are not sufficient to protect the person from harm by themselves or by others, then we don’t just abandon people who are vulnerable. We have to do something to protect them – and a conservatorship as a last resort when everything else has been explored and doesn’t work can be a good thing if it’s enforced properly. But the key to that is monitoring. I think what counties in California should consider replicating - something that’s being done in Nevada – that is they have a legal defense team that represents these individuals in conservatorship. They don’t walk away when the order is entered. They stay on for the length of the case, and they actually send someone from that law office out to the home to check on the person twice a year. This isn’t a government employee. Their role is to protect individual’s rights. We need to have a monitoring system like that for ongoing conservatorships because just having court investigators do it is not enough. When the budget gets tough and sometimes the judges pull the plug on using these court investigators, then the people are just left on their own. So, we need another agency with a mission to truly make sure these people are protected.”

Question: Our investigation, The Price of Care: Taken by the State, focused on holding the Department of Developmental Services accountable. But we also know that California’s probate court system is part of the problem. How do we fix that?

Coleman: “That will take some doing. But first thing is – like I mentioned before – is have the California Chief Justice call for an audit and a census so we know how many people are conserved in each county. Because even the local county judges don’t even know how many people they’re protecting. This is ridiculous. So, that is the first step. Secondly, I think the supervisors in each county need to better fund public defenders’ offices and the court-appointed counsel, legal services – so that the attorneys are holding the court accountable. If the public defender sees abuses or if the court-appointed counsel sees abuses and neglect by the judges themselves or the court investigators, then they can file motions, objections, for new cases coming in they can demand jury trials – they can file appeals. Then when the appellate courts are reviewing these things, they can chastise the judges and public opinions and so the judges will act differently if they know that what they’re doing is being monitored and that they could wind up being the subject of a published appellate decision. It’s going to take monitoring and oversight by the public defenders, the court appointed counsel and also people sending letters to a new chief justice saying, ‘You’re a new chief justice – you’re starting fresh, maybe you don’t know what’s been going on but we’re looking to you as the person in charge of the judicial branch to make sure the local courts are doing the jobs that they should be doing.’ Finally, I think it’s time for the people that are really concerned about this to hold a rally in San Francisco in front of the headquarters in front of the Judicial Council – and then march to the headquarters of the Supreme Court and have hundreds of people in the streets with plaque cards and bullhorns. Sometimes you have to take to the streets to get attention of judges that are sitting in their chambers and ivory towers and are detached from reality. So, we’ve got to get their attention and what’s been happening in Sacramento with rallies and so on is great, but let’s take it to the Chief Justice, to the Supreme Court and to the Judicial Council and have rallies in San Francisco – so those are just a few suggestions of how to bring the courts into line.”