PORTLAND, Ore. —

It was 50 years ago this month that President Richard Nixon signed what would become one of the nation’s most far-reaching environmental laws: the Endangered Species Act. The act was intended to identify species at risk of extinction and implement plans for their recovery.

In some cases, it has done just that. In others, though, the act has proven divisive and contentious, with the people impacted by conservation plans bristling at new regulations that could impact their livelihoods.

Perhaps no species was more emblematic of that conflict in the Pacific Northwest than the Northern spotted owl.

“It was, and to some extent occasionally still is, pretty crazy,” said Paul Henson, a wildlife biologist and former Oregon state supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “You have very opinionated folks on both sides, very passionate, and both sides have very legitimate concerns and complaints and issues.”

Five decades after it was signed into law, with all the rancor and consternation that it’s brought about, has the Endangered Species Act been effective? Are the species granted protection under the act any better off now than they were when they were listed? Have the sacrifices made in the name of saving these species been worth it?

Those questions are very much still open for debate. In the case of the spotted owl, it’s a debate that’s been ongoing for more than three decades.

Old growth, new tensions

By the late 1980s, pressure had been building in the Pacific Northwest for years. Environmental advocates had been trying to stop logging of old growth forests for some time, with increasingly dramatic protests in the woods.

In small communities across the region, timber workers looked at the protests with heightened anxiety, fearful of what new regulations could mean for their livelihoods.

At the heart of the conflict was old growth forests. These forests, generally thought to be 150 years old or older, are complex ecosystems home to a vast array of species. They generally feature towering older trees that form a lush canopy, with smaller, younger trees and a thick understory of shrubs and bushes.

Activists pushing for spotted owl protections took to the forests, blocking logging roads and camping out in trees to prevent timber harvests. In logging towns throughout the Northwest, timber workers and their families rallied against new regulations. The phrase “save a logger, eat an owl” was emblazoned on t-shirts and bumper stickers.

Today, Fran Cafferata is a wildlife biologist who consults for timber companies — but back then she was a little girl who had grown up in the timber industry, fearful of what new regulations could mean for her family.

“My dad is a forester, and my brother is a forester. My mom is a master woodland manager and my family owns and manages about 400 acres in Oregon,” she said. “I just remember it being really a scary time.”

Around the same time, Doug Heiken was just starting his career as a lawyer working for the conservation group that would go on to become Oregon Wild.

“As a native Oregonian, I was a bit jaded about clear cuts,” said Heiken, who is now the conservation and restoration coordinator for Oregon Wild. “I didn't think there was much I could do about it, but when I learned later that we were driving species near to extinction, and there's something we could do about it, it really changed my views.”

Paul Henson, for his part, was just starting his career with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency that would implement protections for the owl.

“It was very acrimonious, very passionate,” Henson said. “People were chaining themselves to trees or to trucks. There was a lot of altercation, a lot of ill will, a lot of fighting.”

At the time, the primary reason for the decline of the spotted owl was clear.

“The main original issue for the spotted owls to climb was habitat loss due to massive clear cutting of the older forests in the Pacific Northwest,” Henson said.

Because definitions of old growth differ, the decline in these types of forests vary, but estimates from the U.S. Forest Service show that old growth covered more than 32 million acres between Oregon, Washington and Californiia in the 1930s. By the 1990s, that number had fallen to around 10 million acres, a decline of more than 60%.

“Imagine the state of Oregon with virtually no old growth forests,” Heiken said. “That's the trajectory we were on in the '70s and '80s.”

That would all change when the Northern spotted owl was finally listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1990.

How to save a species

Once the spotted owl was granted federal protection, wildlife and land managers still had to figure out a plan to keep its numbers from plummeting.

That would come in the form of the Northwest Forest Plan, a massive change in land use policy that set aside roughly 10 million acres of federal land, protecting the old growth that remained, allowing for younger forests to mature and providing buffers along rivers and streams where logging was forbidden.

“During the Reagan years, the last of the big old forests on federal land were being liquidated,” Henson said. “You're talking 200-, 300-, 400-year-old trees that your kids, and my kids, have as much right to as as anyone else, and not as two-by-fours."

“The Northwest Forest Plan stopped that,” Henson said.

For Heiken, the plan represented a sea change in conservation strategy.

“It's an ecosystem plan. It's not just a spotted owl plan,” he said. “It's going to be good for spotted owls, for salmon, for marbled murrelets that live in the coast range. And for all the other species that live in our old growth forest.”

For Cafferata and others in the timber industry, though, the Northwest Forest Plan was what they feared in the run-up to the listing.

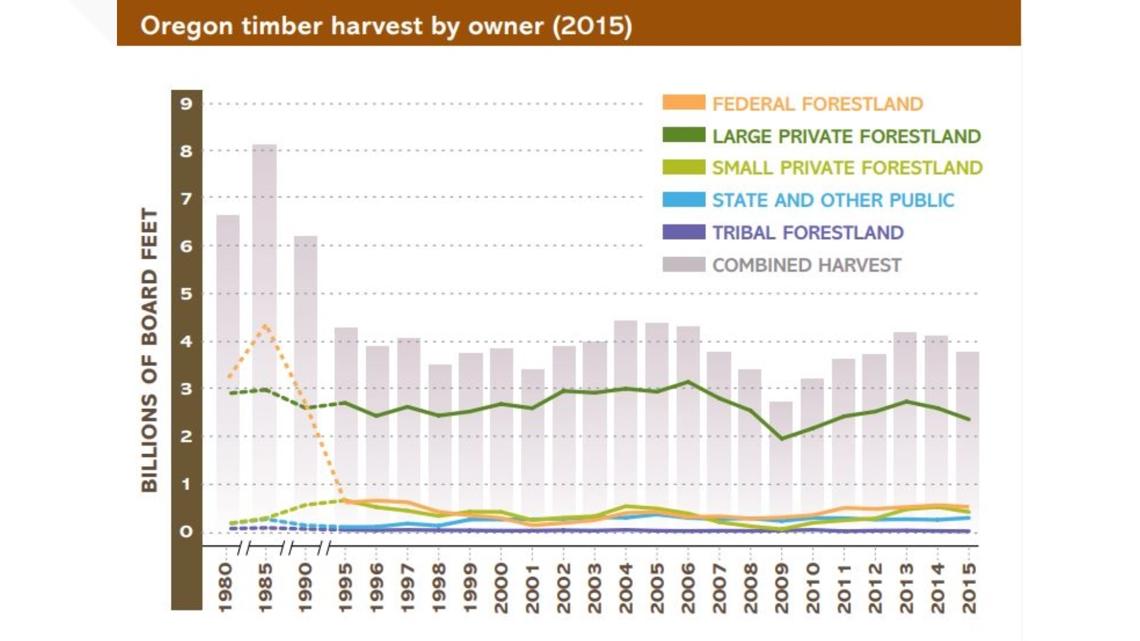

Between 1989 and 1995, timber harvests on federal land fell by roughly 90%, according to the Oregon Forest Research Institute, which pinned most of the blame for the decline on the spotted owl, litigation over timber sales and other endangered species.

“There is no doubt that the listing of the spotted owl had a tremendous impact on the timber industry,” Cafferata said.

Heiken and Henson pointed to other factors at play, though. Timber mills were consolidating, with smaller mills closing in favor of larger operations. Mechanization was also cutting into labor needs, among other economic factors.

“There was a tremendous decline in housing starts and the price of timber was going down, so it was a complicated issue. The spotted owl got most of the blame because it was easy to blame them and it was undeserved,” Henson said. “It definitely had an impact, but not as bad as a lot of the timber industry folks like to say.”

A new threat emerges

More than 30 years after it was listed under the Endangered Species Act, with much of its habitat protected, you might think the Northern spotted owl would be thriving.

That has not been the case, though.

At monitoring sites in Oregon, Washington and California, federal researchers watched as spotted owl populations continued to plummet between 1995 and 2017, in some places by as much as 80%.

Much of that decline was due to the arrival of competition.

Starting in the 1970s, the barred owl began moving into the West from its native range on the East Coast.

“They are territorial species and so they kind of bump each other out of these ideal habitats, and the spotted owl is just a little bit smaller, just a little bit less aggressive and the barred owl is kind of the king of the roost and tends to push the spotted owl into less ideal habitat,” Heiken said.

As Cafferata sees it, the arrival of the barred owl has reshuffled the deck in terms of threats to the spotted owl.

“I think the significant threats to the spotted owl are barred owls and wildfire,” she said. “Those are the two main threats.”

To counter the threat of barred owls, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife last month proposed killing up to 400,000 of the birds over the next 30 years. Studies have shown that removing barred owls from spotted owl habitat has helped stabilize populations of the endangered bird.

But while barred owls may have supplanted habitat loss as the biggest threat to spotted owls, that doesn’t mean habitat conservation is any less important, according to Henson.

“The barred owl is sort of surpassing habitat loss as the biggest, at least most pressing, threat,” he said. “But you're not going to save spotted owls just by taking care of the barred owl. You have to conserve that important older forest habitat for them.”

Heiken put it in terms humans could relate to.

“If your in-laws are going to move into your house, you don't want to make your house smaller. You need to make your house bigger,” he said.

As the threats to spotted owls have changed, the way forests are managed have changed, too, Cafferata said. Timber companies seek out her expertise on how to harvest timber while protecting vulnerable species.

“All the work that I do for the timber companies is voluntary on their part. So, I'm hired to do work that they're not required to do in any way,” she said. “We do it because it's the right thing to do. It's our social responsibility to make sure that we're providing for the critters that live in our forests.”

And the rancor that preceded the spotted owl’s listing in 1990 has, at least in some cases, been replaced by more willingness to cooperate.

“I think we're all hungry for collaboration,” she said. “Anytime we can spend less time fighting and more time working together, we can get more done.”

Heiken acknowledged that progress has been made, but he warned that it will take a concerted effort to maintain it.

“We have to stay on course and show restraint for 100 years, and its yet to be seen whether humans can actually do that,” he said. “If we just slip up for a decade, we’re going to lose a tremendous amount of valuable habitat.”

And that’s important, because preserving old growth does more than just provide habitat for spotted owls, Heiken said.

“We’re also protecting clean drinking water. We’re protecting communities from fire. We’re protecting habitat for a host of other species that live in these old growth forests. We’re providing amazingly special places where families go camping and places with scenic splendor that provide the high quality of life that acts as the foundation for rural economic development,” he said. “When we’re saving the spotted owl, we’re not only saving a bird. We’re saving ourselves.”

This is the first chapter of "Endangered Northwest," a four-part series on the impact of the Endangered Species Act. Look for part two on Tuesday, which will focus on the gray wolf's return to the Northwest.

Part 1: The Northern spotted owl

Part 2: Reintroducing gray wolves